Book Review

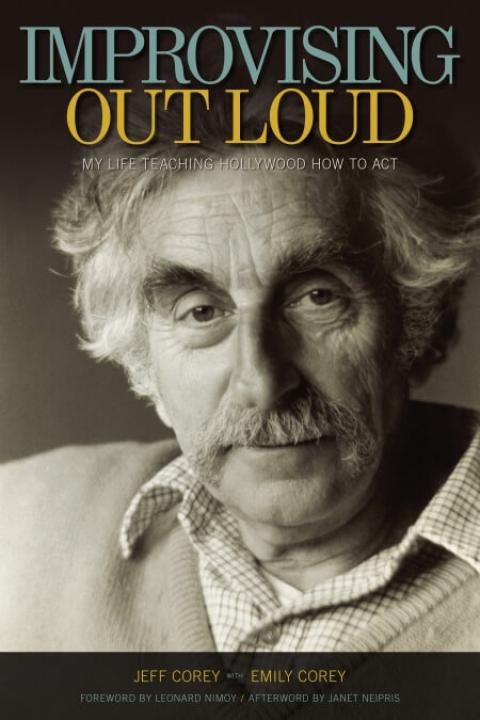

Improvising Out Loud: My Life Teaching Hollywood How to Act.

By Jeff Corey with Emily Corey.

Foreword by Leonard Nimoy.

Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2017, 320pp. $40.00.

Jeff Corey may properly be regarded as personal disproof of the slander, so often heard during the 1950s-60s, that Hollywood film lost nothing important in the blacklist. Film actor Corey’s memoir, completed, edited and prepared for publication by his daughter, Emily Corey, is a tribute to what a left generation accomplished, and on only in front of the camera.

What might seem a most unlikely personality, Leonard Nimoy of Star Trek fame, hails not the actor Corey, but the teacher. In a crisp three-page tribute that recalls the younger actor’s preparation for leading part in Jean Genet’s “Deathwatch,” essentially a career breakthrough, the power and scope of Corey is suggested. If Corey, in a family backyard and a refurbished Los Angeles garage (his own, in fact), trained a generation of screen, television and stage artists, this remarkable saga begins with…the blacklist.

Adolescent Corey had such a boyhood tic that his mother, rising above the Orthodox Judaism of domestic life, took him from Brooklyn to a Manhattan psychoanalyst. Gaining self-confidence, he became a star actor in high school, and on graduation in 1932, threw himself into the theater. Corey was a real intellectual, unlike so many actors, making it inevitable in the Red Decade that he would find the Left or it would find him.

By 1937, that meant a play about the Abraham Lincoln Brigade then fighting fascists in Spain. Soon, he would be involved in productions with other young radical actors including Martin Ritt and Will Lee, writers, directors and writers Albert Maltz, Phil Stephenson and Ben Bengel among others. Corey does not say so, but by 1950, all of them were to go on the blacklist. He insists that his own entry into politics was based on family poverty, but his own keen intellectualism, the breadth of his reading, could not have been absent, or missing Marxism entirely.

Who did he met when he got to Hollywood in 1939? More of same, including Lee J. Cobb (a later sorrowful Friendly Witness), Jules Dassin and Clifford Odets, among many others. He changed his name at this moment, from Arthur Zwerling, and success followed shortly with supporting roles in film after film, often little comedy parts. Meanwhile, he and friends founded Actors Lab, or The Actors’ Laboratory Theater, the leading Method outlet in Tinseltown. A brilliant career as actor and teacher was interrupted by military service in the Navy, Corey personally filming and photographing as he went along, sometimes emceeing shows on the battleship Yorktown.

Success followed success when Corey returned to Hollywood. He makes no point of it, but he must have been proud of the crossover into real drama including Home of the Brave, where as an Army psychologist, he counsels a black serviceman who is under racist attack. His film career ahead looked splendid. Then came the shadow of the Blacklist. The Hollywood Ten, not only the men but their families, were his friends, in the deepest sense, but the shadow did not actually creep over him for a few years. His last film in Hollywood until his return was one that I enjoyed as a kid, and now seems crypto-radical: Superman and the Mole Men (1951) in which Supe defends the little creatures (midgets with rubber baldness) from a redneck mob. He returned with Balcony (1963), the Genet theatrical whose filmic appearance was itself a phenomenon.

He had, as the blacklist fell, already added radio acting to his repertoire, in the years when radio drama hit a high point, including adaptations of many popular films, but mainly dramatic originals like “Philip Marlowe” and “Suspense.” Corey, with his marvelous radio voice, seemed to get all the jobs he wanted. And then he was “Named.” Not that he remained in the same political space as the Communist Party, long since disillusioned with Russia, but to name his friends and associates would be literally unthinkable. Alternatives? He opened an acting studio of his own, in his Los Angeles backyard.

The rest of the story is, perhaps, a little too straightforward. He is a teacher, he has important students, and then he begins to get film work again, shortly before 1960. He had some lame parts, but he also had an abundance of very good ones, in film and television. After Balcony, the avant-garde Mickey One, Cincinnati Kid (with other blacklistees), True Grit and a lot of other mainstream work, nearly always as supporting actor.

Television turned out to be a better venue, with several dozen parts, in shows ranging from Barney Miller, Barney Miller and Night Court to Picket Fences, as the decades rolled on. Those of us who saw him in many parts were amazed most of all, perhaps, at his adaptability. He was an actor’s actor and for good reason: he had trained himself. Indeed, the book closes with Recommended Reading for his students and any acting students.

He was, despite and because of being a very fine actor, above all a great teacher. When I finally met him, at the memorial service of Abraham Polonsky, I felt honored. We mourned the victimized generation together, but also the wonderful contributions that the blacklistees had made and would make so long as they lived.

Paul Buhle is co-author, with Pat McGilligan and Dave Wagner, a half dozen books on the lives and films of the blacklistees.

Spread the word