Hanson Summers first appears in Maryland archives in 1834, when an inventory from Catoctin Furnace, an iron smelter in the ore-rich foothills of Maryland’s Blue Ridge Mountains, lists an enslaved 17-year-old boy by the name of “Henson.” Fifteen years later, the furnace’s owners mention in a handwritten ledger that Henson was being sold for $500 to another iron smelter nearby. Then, in 1899, an obituary in the Hagerstown, Maryland, newspaper lauds Hanson Summers, age 82, who “was noted for his great strength and thought nothing of wheeling half a ton. … He was employed at the Antietam Iron Works.”

Summers’s story of survival and ironworking skill was uncovered by genealogists and historians hoping to tell the story of Black workers at Catoctin Furnace, a hellish place centered on a three-story furnace kept burning for months at a time. Genealogists from the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society tracked down Summers’s descendants, including his 86-year-old great-great-granddaughter, Agnes Jackson. On Juneteenth this year, Jackson and her daughters drove to Catoctin for the first time from their homes in nearby Hagerstown.

“We never knew we were connected to people here,” Jackson says, sitting on a folding chair in a small museum dedicated to the forge and its history. “[Our ancestors] were enslaved—it wasn’t a topic people wanted to talk about.”

Last year, Jackson, who identifies as African American, also took a DNA test: She hoped to learn whether she and her daughters are related to any furnace workers who were buried in a small cemetery near the site. For the first time, answering such a question may be possible, thanks to a new study of DNA of 27 people from that cemetery published today in Science (also see related Perspective).

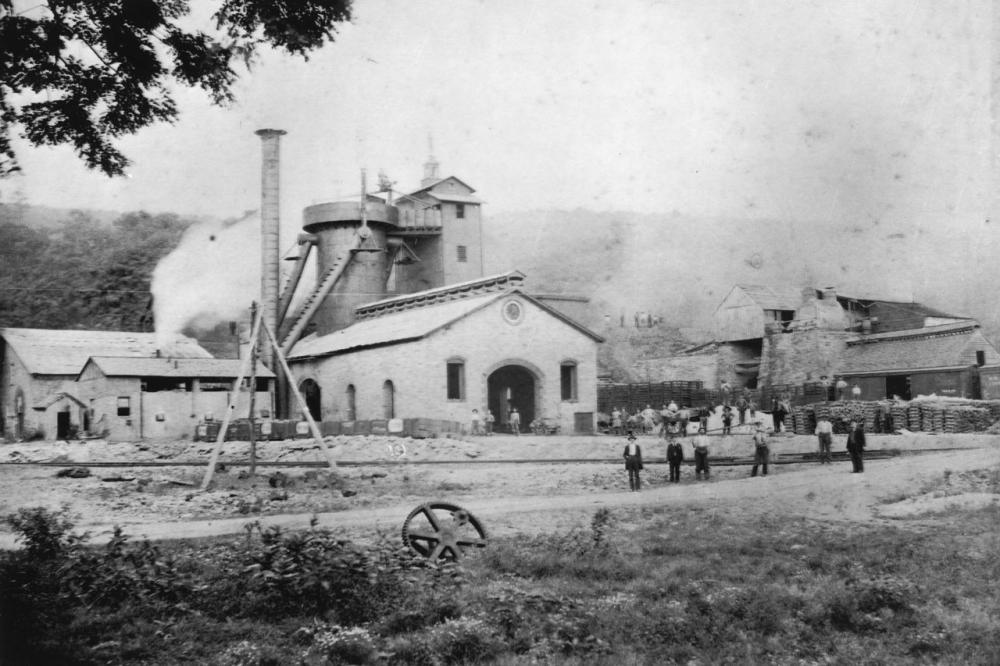

In its early days, enslaved Black laborers worked at the Catoctin Furnace ironworks, shown here in an 1890 photo. CATOCTIN FURNACE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Other analyses of the bones had already offered a glimpse of the harsh lives of enslaved people in an industrial setting. Now, researchers have partnered with the consumer DNA testing company 23andMe to compare the ancient Catoctin Furnace genomes to those of almost 10 million living people in the company’s database. They have identified 41,799 relatives, including hundreds of potential direct descendants. But the company hasn’t yet notified any descendants about their results, as it works through the ethics of contacting people who agreed to let their data be used in anonymized studies. At the same time, researchers are wary of traumatizing people unprepared for links to enslaved ancestors.

Many in the Black community say such information—when collected with community consent—would have poignant value. “For marginalized communities whose history has been obscured, this technology can be leveraged to tell their stories,” says Jada Benn Torres, a Black biological anthropologist at Vanderbilt University who was not part of the new study. “There’s a beauty in connecting the past to the present.”

“Connections to the past were severed because of the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” explains Carter Clinton, a geneticist at North Carolina State University who is African American. (When possible, Science uses sources’ own preferred identification, such as African American or Black.) “Today there’s a thirst for knowledge. How do we reconstruct those lives and find out where our ancestors came from, and what does that mean for how I identify today? It’s something we want and don’t have in comparison to other ethnicities in America.”

But rapid advances in genetics and genealogy open up hard questions about the power dynamics of studying the remains of enslaved people, such as who speaks for communities with no known genetic descendants. “This is one of the better executed projects I’ve seen in terms of the way they included the community and have been thoughtful about including Black American scholars,” says Alexandra McDougle, a Black archaeologist at Columbia University. But, she says, “There’s so much farther to go.” Some think the Catoctin researchers didn’t do enough to involve today’s Black community, for example.

Clinton adds that linking DNA from historic remains to known living relatives “is significant for every African American in this country, and I’m rooting for a way to figure out how to make this happen ethically. The question is, who is the ultimate decision-maker” in making those connections?

TODAY, CATOCTIN FURNACE SITS just off Maryland’s Highway 15, at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains 80 kilometers north of Washington, D.C. On a muggy but cool June morning, Elizabeth Comer pushes into the woods, headed for the cemetery. The trees are still dripping from showers the night before, and the thrum of cars nearby is constant.

Two hundred years ago, the noise around the cemetery would have been different—the hammering of iron, ringing of picks in an adjacent ore pit, and roar of a bellows-fired blast furnace—but just as oppressive. “It was never quiet,” says Comer, a white archaeologist and president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. “It still isn’t.”

Sharon Green, Vicki Winston, and Barbara Hart (left to right), at the ruins of the Catoctin Furnace site, are the great-great-great-granddaughters of one of its enslaved workers, Hanson Summers. KINTSUGI KELLEY-CHUNG

As she picks her way through thick undergrowth, Comer, who grew up nearby, describes the furnace’s history starting in the 1760s, when it was founded to supply metal for the fast-growing American colonies. Catoctin churned out shells, cannonballs, and kettles for the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. After the war ended, production shifted to peacetime products such as stoves, pots and pans, and raw “pig iron.”

When the furnace ran, a waterwheel turned a massive bellows, heating charcoal in a stone chimney, or “stack,” 10 meters high. Fires blazing for months at a time, the stack’s hunger for fuel stripped nearby slopes bare of trees. Dozens of workers and families lived and toiled under a constant pall of smoke.

From its first days, the furnace’s white owners likely used Black labor for the hardest jobs, Comer says. Black workers were responsible for everything from keeping the massive furnace fires burning to channeling molten iron into sand molds. Work was constant. A German-speaking Moravian pastor, Frederick Schlegel, described conditions at the forge as “lamentable” in his diary after visiting in 1799. He recalled that enslaved workers crowded up to him and “complained how hard they work every day, including Sundays, to keep the iron flowing.”

In the 1830s and ’40s, many of the forge’s enslaved workers were sold, like Summers, or leased to other iron works, then gradually replaced by immigrants from Ireland, England, and Germany, who had to pay furnace owners for food and lodging. “There’s this sudden replacement by free European labor, and it’s not clear where the Black community went,” McDougle says. Twentieth century historians lauded the immigrants’ contributions but skipped over the pivotal role of Black workers.

The cemetery was forgotten, too, until an archaeological survey ahead of highway construction revealed human remains. In 1979 and 1980, a rescue excavation uncovered 35 graves, 32 of which contained human remains. Some of the simple, uncarved white and gray stones used as grave markers still sit today in the woods where archaeologists set them aside more than 40 years ago. The graves were dated to about 1800, and features of the bones showed they belonged to people of African ancestry. Maryland officials later transferred them to the Smithsonian Institution, where they sat in storage for decades.

In 2014, Comer started to search for local families with ties to the cemetery to help tell the site’s story. She was stymied by the lack of records: Dozens of people who lived at the forge in the early 1800s are remembered only as fleeting, first-name entries in inventories and diaries: Milly, Hercules, Bob, Clowy, Lusinda, Elizabeth, Andrew. Their stories and connections to living individuals were lost; Comer was able to reconstruct Summers’s story only because his first name was unusual.

In that sense, Catoctin Furnace is far from unique. Until the census of 1870, U.S. records only rarely referred to enslaved Black people by full name. Enslaved families were often broken apart on purpose, splintering family trees. For Black people seeking their ancestors, that created “a brick wall of slavery prior to 1870,” says historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. of Harvard University, a co-author on the new study, who is African American. To see beyond that wall, Comer, also a co-author, applied for a grant to reanalyze the cemetery’s bones. She hoped new methods, including ancient DNA analysis, would tell a more complete story about Catoctin’s Black workers.

DNA SAMPLING PRESENTED a chicken-or-egg ethical problem: Until scientists had DNA results from the unnamed individuals in the cemetery, they couldn’t get consent from genetic descendants to sample remains. So they applied a broader definition of “descendant,” expanding it to local Black community members, whom they asked about the study.

This expansive concept of kinship, which originated with work in the 1990s at the New York African Burial Ground in lower Manhattan, has been applied in the handful of other studies of the DNA of enslaved people. “It could be a community that’s not related but is residing in the region, who share a story and feel a responsibility for that enslaved community,” explains Clinton, who did his Ph.D. work on the African Burial Ground, now a national monument. “Because of these broken lineages, you can define descendant in different ways—not just ‘am I genetically related to you,’ but ‘are you invited to the cookout?’”

Comer and Smithsonian curators sought support from the African American Resources Cultural and Heritage (AARCH) Society, a nonprofit in Frederick, Maryland, focused on documenting the county’s African American history. AARCH Society members visited the Smithsonian lab in 2016, and the group’s then-president supported the studies, including drilling into the bones for DNA. “When this started I didn’t have a direct descendant community,” Comer says. “Now, thank God, we’re getting one.”

Members of the Summers family look at a photo of their great-great-grandfather Emory, the son of Hanson Summers, who once labored at the Catoctin Furnace.AMERICA’S HIDDEN STORIES: FORGED IN SLAVERY/SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL

Before geneticists began to extract DNA, biological anthropologists at the Smithsonian studied the human remains in an attempt to reconstruct life at the furnace. The bones offer testimony to conditions different from those at plantations, and at least as harsh. Nearly half of the 32 graves contained the remains of children under age 4, some of whom had bowed lower legs—a classic symptom of vitamin D deficiency known as rickets. A smoky haze so thick it blocked the Maryland sun, much like a wildfire, likely reduced vitamin D production in skin.

By analyzing heavy metals in the bones, the researchers were able to document individual exposure to toxins. Some people had high levels of lead and zinc; one man in his late 40s had zinc levels nearly triple that of most enslaved people in the region. He might have worked as a “filler,” shoveling charcoal and zinc-rich iron ore into the blazing furnace, Comer says.

Other results set Catoctin apart, too. In the 19th century, death usually claimed the very young or very old, or women in childbirth. But the 32 people excavated at Catoctin include five teenage boys. “Jobs that were considered menial labor were pretty dangerous, and if you weren’t skilled you were at risk from dying,” says co-author Kari Bruwelheide, a white biological anthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). “They were doing jobs they weren’t physically ready for.” One boy who died at age 12 or 13 had a dislocated shoulder; a 15-year-old had herniated discs.

One elderly man Bruwelheide examined had such severe spinal damage, he would have been bent nearly double when he died. An 1804 entry in Schlegel’s diary offers an uncanny reference that might be a match. “I then visited a cripple who walked all bent over,” Schlegel wrote. “He lives in great need.” (Even the missionaries perpetuated identity loss for enslaved people: Schlegel and his brethren omitted the names of the Black forge workers they baptized and buried, while dutifully recording white identities.)

A memorial honors the enslaved people buried at the Catoctin Furnace cemetery, many of whom are still unnamed or known only by first name. KINTSUGI KELLEY-CHUNG

In 2017, geneticist David Reich of Harvard, who is white, and his colleagues joined the team. They sampled DNA from the remains and sequenced the whole genomes of 27 people, identifying five family groups of mothers and children within the cemetery. None included any adult male relatives, possibly a sign men and women were buried separately, in keeping with the Moravian missionaries’ traditions. Comparing the DNA in the Catoctin samples with databases of modern populations revealed that more people in the cemetery had European ancestry through the male than the female line, consistent with historic evidence of owners fathering children with enslaved Black women.

Comer wondered whether scientists could link the unnamed bodies at Catoctin Furnace to living people. “By 2020, ancient DNA technology was close to being able to find connections between people who lived in the past few hundred years and people today,” says co-author Éadaoin Harney, then a Ph.D. student in Reich’s lab and now a researcher at 23andMe. “We wanted to develop this technology and apply it to historic populations where it would have the most impact.”

Deploying modified versions of the tools 23andMe and other direct-to-consumer companies use to find genetic relatives, Harney identified stretches of DNA shared between people in company’s database and people in the cemetery, segments called “identical by descent” (IBD). “The more and longer segments you share, the closer your relationship,” Harney, who is white, explains.

Most of the 41,799 people who matched had just a few, short IBD segments in common with people from Catoctin Furnace. That suggests distant connections dating back centuries, to shared ancestors in Africa or Europe who lived generations before the cemetery was in use.

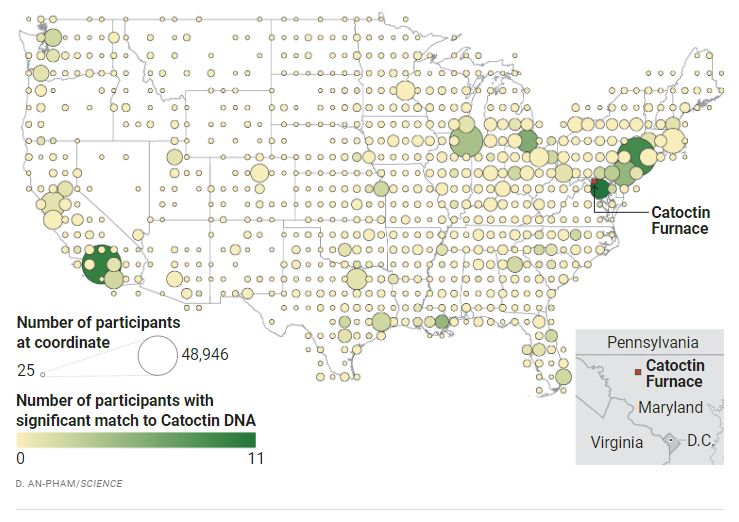

Harney also identified 2975 living people in the 23andMe database who shared significantly higher amounts of DNA with the people from Catoctin Furnace. Some were estimated to be as little as five degrees removed—the equivalent of a great-great-great-grandparent, about right for a direct descendant 225 years later. Because 23andMe’s database includes geographic data, Harney could even suggest where the cemetery’s descendants ended up. Many families didn’t go far—dozens of very close relatives still live in Maryland, and many more are spread across the southeastern United States (see map, below). To protect participants’ privacy, only employees of 23andMe know the exact locations.

Catoctin’s living legacy

Researchers used 23andMe’s massive genetic database to trace living people who share significant DNA with enslaved people buried in the 19th century at Catoctin Furnace. Many descendants still live near Catoctin, with another cluster in California. (To preserve privacy, the company blurred the precise locations of participants, bumping some data outside U.S. borders.)

But for now, those descendants remain unaware of the connection. People in the 23andMe database whose sequences were matched to those of the Catoctin workers signed a consent form with the company allowing use of their DNA for “a wide variety of research topics.” But the agreement promised their data would be anonymized and results would not be returned to them directly. The company is still working out how to ethically offer most people the possibility of being directly connected to their forebears.

SUMMERS IS NOT buried in the Catoctin cemetery: He died more than half a century after it fell into disuse. On Juneteenth, sitting on a folding chair in the museum, his great-great-granddaughter Jackson pondered the mystery of her family’s link to the site.

Jackson is old enough to remember drinking from segregated water fountains and watching movies from the Black-only balcony of the local theater. But she doesn’t remember hearing her parents, farmers who lived on the outskirts of Sharpsburg, Maryland, ever talking about Catoctin as part of the family’s history. “We never knew we were connected to people here. This has taught me we didn’t know everything about our family.”

For Jackson’s daughter Sharon Green and her sisters, the lack of documentation as well as the horrors of slavery discouraged deep genealogical research. “We only knew to go back to our grandparents. We didn’t know there was anything beyond that to be found,” Green says.

Connecting the furnace workers to living descendants, as the new study aims to do, could be a way to address past injustices, says Fatimah Jackson, an African American geneticist at Howard University. If Catoctin descendants can be made aware of their DNA results, she says, people could “make connections that were intentionally severed to prevent uprisings and community-building. It’s a way to say, ‘you didn’t win, we’re winning.’”

But others think the team behind the study could have done more to put descendants and their questions at the forefront. Indeed, spurred by the Black Lives Matter movement, a group of researchers in 2021 published a call to pause research on African American remains entirely until laws are passed to address consent and access to data.

That appeal came well after the Catoctin research was underway, Still, the current AARCH Society leaders feel the consent given more than a decade ago is no substitute for broad community engagement. “[Scientists] need to build a relationship with the community, and it’s going to take more than a nod from AARCH to do that,” says the group’s current president, Protean Gibril.

Rachel Watkins, a Black biocultural anthropologist at American University who has worked with AARCH Society members and families in western Maryland, says securing support from the society to take samples was the bare minimum. More engagement should have followed the decision to restudy the bones, Watkins argues, but AARCH Society members were sidelined. “Based on current engagement models, merely showing results to communities isn’t adequate,” Watkins says. The collaboration with 23andMe, for example, could have drawn on the AARCH Society’s genealogical knowledge about the local Black community to guide study design.

Watkins also thinks the project could have worked harder to let descendants’ questions steer the study. Some African Americans in Maryland have in fact been able to break through the “brick wall” and trace their ancestry back well before the 1870s, she says. The project could have asked those descendants what they’d like to know about the Catoctin people, Watkins says. “What they’ve discovered doesn’t necessarily address questions people who have broken through the wall might have.”

The manor house at Catoctin Furnace stands in ruins.KINTSUGI KELLEY-CHUNG/AAAS

But Gates vigorously defends the project’s ethics and approach. “Rather than this being an example of exploitation of a vulnerable population, it is an example of the opposite: of deploying scientific tools to address questions of long-standing interest to African Americans, and at the community’s request,” Gates says. “The study is a tool for empowerment of African Americans. I would not have joined the study or been so enthusiastic if that was not the case.”

Another point of tension is publication of the raw genetic data, which is typical in ancient DNA studies. Some historically marginalized communities, however, fear the loss of control and privacy that comes with such publication. For example, when researchers obtained DNA from 36 people at the Anson Street African Burial Ground in Charleston, South Carolina, the research was published, but the DNA sequences were not deposited in open databases and any future research requires the local community’s permission.

NMNH, where the Catoctin remains are housed, requires open access to data generated from sampling its specimens. The data in the Science study were posted on the European Nucleotide Archive last year, allowing anyone to access it. Reich argues that in this case, open publication of data was important to help prevent commercial exploitation. “We didn’t want 23andMe to have exclusive access,” he says. “The only ethical approach is to make the historical data fully publicly available, so that the for-profit company cannot have proprietary ownership over data. This is particularly important for DNA from enslaved individuals who did not have agency over their remains.”

But open data can lead to exploitation, too. In a development Reich calls “negative,” some companies are using the genes of enslaved people to tout genetic ancestry analyses, often without clear explanations of their methodology. History sells: Customers are lured by the chance of finding genetic links to Viking shield maidens, Roman gladiators—and, since their 27 genomes were posted on a preprint server last summer, enslaved Black people from Catoctin Furnace. “Historical evidence shows African slaves were chosen with backgrounds in iron manufacturing,” the website of Switzerland-based MyTrueAncestry reads. “You can find out if they are part of your ancestry. FIND OUT HOW.”

Comer keeps a spreadsheet tracking nearly 200 hopeful inquiries she’s received since the company incorporated Catoctin Furnace into its marketing last summer. Based on what MyTrueAncestry has released about its methods, she thinks most inquirers are about as related to Catoctin as anyone with some African ancestry—very, very distantly. “Is that exploiting the desire within the African American community to have more information about their ancestry? Yes,” she says. “It’s given a lot of people false hope.”

But Comer defends her project’s overall impact, saying it has helped build a Black descendant community at Catoctin Furnace that otherwise wouldn’t exist. “I can’t say the project started with the community of descendants, because it didn’t,” Comer says. “And it could have, had they been in a position to know the cemetery existed and these advances in archaeology existed.”

ALTHOUGH MANY PEOPLE are eager to learn the stories of their enslaved ancestors, others might find the information traumatic, Comer and Reich say. They and their collaborators note this concern in a commentary published this week in The American Journal of Human Genetics. “A huge part of this research is the responsibility to disseminate information in a sensitive way and be prepared for the psychological impact it might have,” Clinton says.

Some descendants may be unaware of their links to slavery or even to the Black community. For example, at the moment there’s just one other Catoctin worker whose descendants have been identified. In 1979, around the same time researchers were excavating the Catoctin Furnace cemetery, Steven Pilgrim, a materials scientist at Alfred University who identifies as white, made an unexpected discovery in Pennsylvania state archives. “The 1910 census shows my great-grandmother was Black,” Pilgrim says. According to family lore, Manzella Grace Patterson died in childbirth in 1914, at age 38. Her husband remarried soon thereafter.

Distant cousins Crystal Claggett (left) and Steven Pilgrim both count a freed Black worker at Catoctin Furnace among their ancestors. KINTSUGI KELLEY-CHUNG/AAAS

Pilgrim kept digging, eventually tracing his great-grandmother’s ancestry back to a free Black ironworker named Robert Patterson, who lived near and labored at Catoctin Furnace in the mid-1800s. Pilgrim and other family members have since compiled a list of more than 1000 living Patterson relatives. Many have become part of the Catoctin Furnace community, participating in events on-site and getting briefed on the genetic research at the cemetery. However, the family may not be genetically related to anyone buried in the cemetery, which was no longer in use by the time Pattersons crop up in Catoctin records.

Comer recognizes that not every family might welcome news of connection to the cemetery. “When I look at the 23andMe results and see Maryland light up, I have a feeling I know some of these people—and they may not know, or want to know, they’re related to skilled African American ironworkers,” she says. “That’s the American story, and that’s the story here.”

As researchers think through the ethics of contacting descendants, medical research can provide a model for consent, suggests Alondra Nelson, a sociologist of science at the Institute for Advanced Study, who is African American. “If you’re doing genome-wide analysis and find someone has a disease, some people want to know, others don’t,” she says. The key is to ask before doing the study. If people didn’t agree to learn about genetic connections with historic individuals when they submitted their DNA to 23andMe, it might not be ethical to contact them now, she says.

Clinton agrees, and also thinks 23andMe’s clients should have been able to specifically consent—or decline—to have their DNA used in work on historic people. “People should be fully aware of how their data is being used, especially if it’s being used downstream in other ways that are not directly beneficial to them,” he says.

Agnes Jackson and her daughters, the known descendants of Summers, with Pilgrim and other Patterson family members, were briefed on the overall DNA results in a video call with Comer, Harney, and Reich in early June. For them, more answers are on the way: 23andMe said in a statement that it plans to return results to the two documented descendant families, with the help of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society and the Smithsonian.

As the afternoon of Juneteenth shaded into dusk, Jackson’s daughter Green looked around the Catoctin Furnace museum. For now, she says, the realization that their ancestor was a metalworker has changed the way she views her past. “They always made it out that we were so uneducated and insignificant, that our past began with cotton and ended with cotton,” she says. “When I look at the price they paid for him, that skill set—it blows me away. We were educated people, with valuable skill sets.”

Andrew Curry is a journalist in Berlin.

Join AAAS. Be an advocate. Advance the world of science.

By joining AAAS, you're strengthening the voice of science. Your membership means uniting STEM professionals and enthusiasts across the globe to support new discovery, innovation, and science education.

Quantum Complexity Shows How to Escape Hawking’s Black Hole Paradox

Inside of a black hole, the two theoretical pillars of 20th-century physics appear to clash. Now a group of young physicists think they have resolved the conflict by appealing to the central pillar of the new century — the physics of quantum information.

Charlie Wood

Quanta Magazine

August 2, 2023

Spread the word