On December 15, 1811, the London Statesman issued a warning about the state of the stocking industry in Nottingham. Twenty thousand textile workers had lost their jobs because of the incursion of automated machinery. Knitting machines known as lace frames allowed one employee to do the work of many without the skill set usually required. In protest, the beleaguered workers had begun breaking into factories to smash the machines. “Nine Hundred Lace Frames have been broken,” the newspaper reported. In response, the government had garrisoned six regiments of soldiers in the town, in a domestic invasion that became a kind of slow-burning civil war of factory owners, supported by the state, against workers. The article was apocalyptic: “God only knows what will be the end of it; nothing but ruin.”

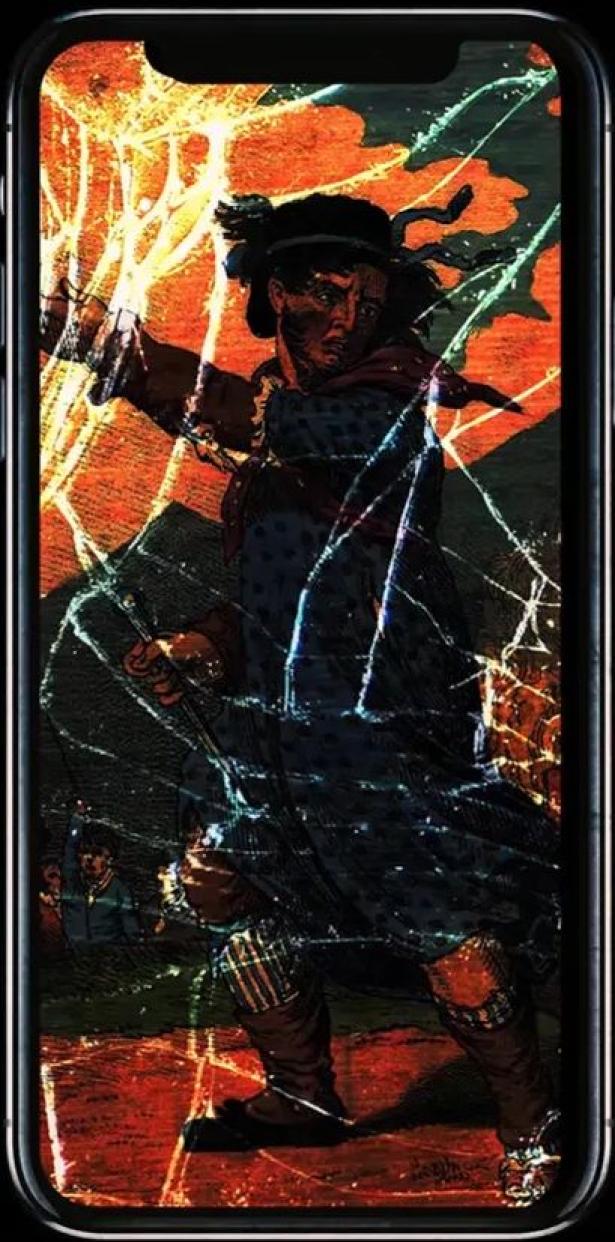

The workers destroying the lace frames were the group who called themselves Luddites, after Ned Ludd, a (likely fictional) knitting-frame apprentice near Leicester who was said to have rebelled against his boss by destroying a frame with a hammer. Today, the word “Luddite” is used as an insult to anyone resistant to technological innovation; it suggests ignoramuses, sticks in the mud, obstacles to progress. But a new book by the journalist and author Brian Merchant, titled “Blood in the Machine,” argues that Luddism stood not against technology per se but for the rights of workers above the inequitable profitability of machines. The book is a historical reconsideration of the movement and a gripping narrative of political resistance told in short vignettes.

The hero of the story is George Mellor, a young laborer from Huddersfield who worked as a so-called cropper, smoothing the raised surface of rough cloth with shears. He observed the increasing automation of the industry, concluded that it was unjust, and decided to join the insurgent Luddite movement. A physically towering figure, he organized his fellow-workers and led attacks on factories. One factory owner who was targeted was William Horsfall, a local cloth entrepreneur. Horsfall threatened to ride his horse through “Luddite blood” in order to keep his profitable factories going, hiring mercenaries and installing cannons to defend his machines. In the background of the story, figures such as the ineffectual Prince George, a sybaritic regent for his infirm father, George III, and Lord Byron, the poet, who voiced his sympathy for the Luddites in Parliament, debate which side to support: owners or workers. Byron exhorted the workers in his poem “Song for the Luddites” to “die fighting, or live free.”

Merchant ably demonstrates the dire stakes of the Luddites’ plight. The trades that had sustained livelihoods for generations were disappearing, and their families were starving. A Lancashire weaver’s weekly pay dropped from twenty-five shillings in 1800 to fourteen in 1811. The market was being flooded with cheaper, inferior goods such as “cut-ups,” stockings made from two pieces of cloth joined together, rather than knit as one continuous whole. The government repeatedly failed to intervene on behalf of the workers. What option remained was attacking the boss’s capital by disabling the factories. The secretive captains of the Luddite forces took on the pseudonym General Ludd or King Ludd, which they used to write public letters and to sign threats of attacks. The spectre of violence led some factory owners to abandon their plans for automation. They reverted to manual labor or closed up shop completely. For a time, it seemed that the Luddites were making headway in empowering themselves over the machines.

The book offers plenty of satisfying imagery for the twenty-first-century reader experiencing techlash. Merchant argues that the message of Luddism is just as relevant today, as our lives become increasingly enmeshed with digital platforms, from TikTok to Uber and Instacart, that translate our labor and attention into profit, “overlaying a sort of psychic factory onto its workers’ lives.” (Who hasn’t at times wished to take a hammer to their MacBook?) The Luddites sought revenge against the innovation that was holding them hostage. In Merchant’s telling, they were activists, punks, and masked celebrities standing up for the skilled working class, the successors to Robin Hood, another product of Nottingham. “Luddite” by that measure sounds like a compliment.

“Blood in the Machine” is being published just as we are facing a new wave of technological automation centering on artificial intelligence—which some, including the consulting firm McKinsey, have labelled the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Merchant uses anachronistic terms like “startup” and “tech titan” to describe early factories and entrepreneurs, seeking to draw parallels with the present. (The book’s analytical sections are weaker than its narrative ones.) The “labor-saving technology” of today threatens new categories of jobs: customer service is being performed by chatbots; Amazon is selling e-books written by ChatGPT. Designers and illustrators are losing jobs to image generators; translators are being asked to “clean up” transcripts generated by A.I. The profusion of dubious A.I.-generated content resembles the badly made stockings of the nineteenth century. At the time of the Luddites, many hoped the subpar products would prove unacceptable to consumers or to the government. Instead, social norms adjusted. Both the mass-manufactured products and the regimented jobs that produced them quickly became entrenched.

The Luddites watched as sprawling factory buildings rose over their rural towns, concentrating labor that had traditionally been performed independently in the home or small workshops. The working conditions in those factories, often staffed by children, were execrable; the horror stories that emerged, of mangled limbs and bodies, eventually helped encourage reform. The victims of automation today are less immediately obvious. ChatGPT users can’t see the low-paid content moderators in countries such as Kenya who undergird the program’s output, performing an onerous psychological task that studies have shown can induce P.T.S.D. There is no single machine that can be smashed to disable artificial intelligence. If the physical server farms that host A.I. programs were attacked, the software could simply be hosted elsewhere. What’s more, the foundation of A.I. is the raw material that humanity has already labored to produce: reams of text and images that programs process into patterns and then remix into fresh “content.” Unlike the machines of the first Industrial Revolution, A.I. does not necessarily need more input; it can sustain itself. “Jobs are definitely going to go away, full stop,” Sam Altman, the C.E.O. of OpenAI, recently told The Atlantic.

The tragedy of the Luddites is not the fact that they failed to stop industrialization so much as the way in which they failed. In the end, Parliament “sided decisively with the entrepreneurs,” as Merchant writes, and frame-breaking was made a capital offense. Dozens of workers were executed for Luddite activities, including, in January of 1813, fourteen in one brutal day. George Mellor, the Luddite captain, was eventually convicted of assassinating Horsfall, the factory owner, and was hanged, at the age of twenty-three. Human rebellion proved inadequate against the pull of technological advancement.

“Blood in the Machine” suggests that although the forces of mechanization can feel beyond our control, the way society responds to such changes is not. Regulation of the textile industry could have protected the Luddite workers before they resorted to destruction. One proposal suggested a tax on every yard of cloth made by machine. After a pro-worker bill failed to pass in the House of Lords, Gravener Henson, a frame knitter turned advocate and historian, led an association of workers that demanded higher wages and labor protections, though such “combination” was outlawed at the time in the U.K. Eventually, Luddism faded into a more general political movement. By the late nineteenth century, the majority of Nottingham’s lace production had been mechanized. In the era of A.I., we have another opportunity to decide whether automation will create advantages for all, or whether its benefits will flow only to the business owners and investors looking to reduce their payrolls. One 1812 letter from the Luddites described their mission as fighting against “all Machinery hurtful to Commonality.” That remains a strong standard by which to judge technological gains. ♦

Kyle Chayka is a staff writer for The New Yorker and the author of “The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism.”

Since its founding, in 1925, The New Yorker has evolved from a Manhattan-centric “fifteen-cent comic paper”—as its first editor, Harold Ross, put it—to a multi-platform publication known worldwide for its in-depth reporting, political and cultural commentary, fiction, poetry, and humor. The weekly magazine is complemented by newyorker.com, a daily source of news and cultural coverage, plus an expansive audio division, an award-winning film-and-television arm, and a range of live events featuring people of note. Today, The New Yorker continues to stand apart for its rigor, fairness, and excellence, and for its singular mix of stories that surprise, delight, and inform.

The weekly magazine is available in print, at newsstands, and by subscription. Digital subscribers have access to our complete archive, which includes a digital replica of every issue of the print magazine, from 1925 to today.

Spread the word