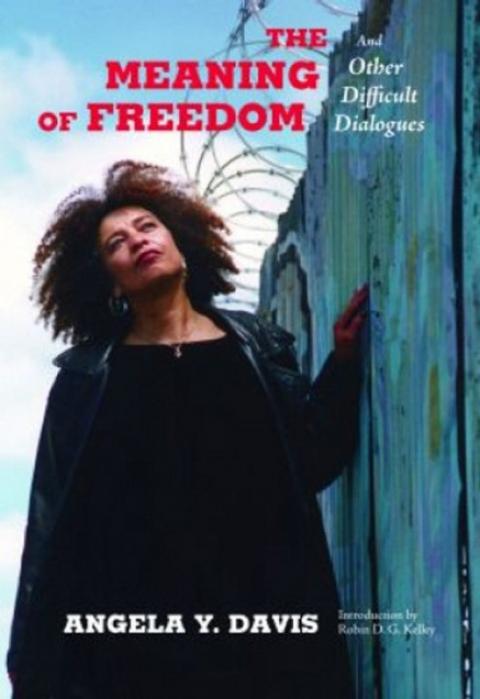

The Meaning of Freedom

And Other Difficult Dialogues

by Angela Y. Davis

Introduction by Robin D.G. Kelley

$15.95 - paperback

The book, comprising 12 speeches Angela Davis delivered between 1994 and 2009, brings out her philosophy of freedom and justice.

"Unless the powerful are capable of learning to respect the dignity of their victims... impassable barriers will remain, and the world will be doomed to violence, cruelty and bitter suffering." --Noam Chomsky

There is a long journey from transcendent truth to relative truths. On the one end is the notion of knowledge as power; on the other is the notion of knowledge as a liberating experience, a means of presenting numerous interpretations without the significance of the established "truth" ever restraining individual freedom.

Helene Cixous, the French theoretician, is of the view that "there has to be some `other' - no master without a slave, no economic-political power without exploitation, no dominant class without cattle under the yoke, no `Frenchmen' without wogs, no Nazis without Jews, no property without exclusion". This Hegelian dialectic works in almost all areas of power and knowledge and in patriarchal structures apparent in the working of master narratives as seen even in the recent Oscar-winning film Argo, which reinforces the "othering" of Iran. The rise of fascism is underpinned by irrationality becoming part of reason and nudging it towards an involvement with tyranny and domination. But the long journey from Jehovah to Jesus, from the Old Testament to the New, from tyranny to human rights is a journey that counsels all, as stated in the Book of Isaiah, to "seek justice, correct oppression, defend the fatherless, plead for the widow". More than a religious statement, it becomes a political axiom aspiring to liberation from tyranny and to non-violence and community and social justice.

Angela Davis, the radical political thinker who lectures extensively on social and political issues, brings out her philosophy of freedom and justice in the 12 speeches, delivered between 1994 and 2009, that have been compiled in her book The Meaning of Freedom and Other Difficult Dialogues. Her ideas on freedom are contrary to the notion of individualism wherein a person can do what he wishes without any restraint and as long as it is lawful. Such a negative form of freedom that allows the defence of property even with the use of weapons is too narrow a concept for Angela Davis. For her, freedom is more "expansive and radical". To her, freedom from violence, sexual freedom, social justice, abolition of all kinds of bondage and incarceration, and freedom of movement are far more significant features than the mere selfish strivings of an individual, a philosophy of Thomas Hobbes she vociferously disagrees with.

Born into apartheid social system in Birmingham, Alabama, Angela Davis, like other dissident voices of her times such as Martin Luther King Jr, Howard Zinn, Edward Said and Noam Chomsky, unremittingly indicts the forces of American imperialism, neoliberal capitalism, heterosexist patriarchy and racist intolerance spanning contemporary American history. Her activism in the 1960s and her joining hands with the Black Panther Party led to her incarceration for over 18 months when both the then President Richard Nixon and the then Governor of California Ronald Reagan took measures to ensure that she never returned to her teaching assignment in the University of California. Her crime was her ideological affiliations with the communist party.

But her chief focus has been a scathing critique of the institution of prisons and the racist bias in the processes of punishment and incarceration within the United States. The majority of the people sent to prison every year are blacks and browns. Their incarceration leads to their segregation from society and, according to Angela Davis, further intensifies the criminal behaviour rampant in society. Interestingly, speaking about the victory of George W. Bush in 2000, she says in her lecture on "Race, Power and Prisons since 9/11": "We cannot forget that before 9/11, anti-prison activists had pointed out that a large-scale disenfranchisement of prisoners and former prisoners enabled Bush's rise to power. Had a small fraction of the 400,000 black men who were barred from voting in the contested state of Florida (because they were either felons or former felons) been able to vote, Bush would not have even emerged as a serious contender."

The speeches are remarkable for their spontaneous sincerity and ideological force, which are intended more to educate a sceptical audience than just to convince. They reveal the passions and perils of a life that is in search of a more politically charged and ethically consistent world view. The book on the whole comes across as a courageous effort to look at multiple perspectives of the idea of freedom, which is intrinsic to any civil society that believes in the notions of justice and equality.

Any modern-day bias towards the minorities amounts to a type of slavery and goes against any utopian notion that racist politics is at an end in the U.S. The abolition of the slave trade, Abraham Lincoln's famous 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and the Civil Rights Act have failed to usher in a racist-free environment right up to the present day as is visible in the statistics which show that "prisons thrive on inequality". So much of finance is diverted for prison construction that much-needed educational infrastructure for the downtrodden is substantially ignored. Employment opportunities are another much-neglected area.

Indeed, Angela Davis' lectures take the reader towards a serious reconsideration of ideology and the state apparatus and the deplorable question of oppression on the basis of race, gender, class and sexual orientation that exists in the U.S. and the world at large. The wholesale criminalisation of young black men cannot be permitted and the concept of rehabilitation has to find some ground.

Angela Davis' focus has been on the institution of prisons and the racist bias in the processes of punishment and incarceration in the United States. Here, a view of a guard tower and fence at California State Prison, Sacramento, in Folsom, California. (Frontline)

Her clarion call to us is to feel connected to the future that is possible only through struggle for structural change in our society: "So I want to begin by suggesting that whoever you are, wherever you are, whether a student, a teacher, a worker, an artist, there are always ways towards progressive, radical transformation." Her speeches criticise institutional injustice and explore the notion of freedom, not so much as a fundamental right guaranteed by the legal and political machinery but as something that grows from the collective and participatory social process crying out for a more liberating environment in which new ways of thinking and being can flourish. Such provocative and exuberant activism underpins the formation of a significant dissident voice, both confident and outrageous, that will for decades to come ignite any social or political movement of human rights and freedom across the world.

I believe that revolutions occur when an intellectual who knows the pulse of a nation inspires those outside the ivory tower, exhorts them to action, leads them through it and empowers them to sustain the movement until change occurs. It is a daunting task, one that nations are ripe for. But where are our inspired intellectuals? We need millions like Angela Davis to effect any change. We also need academics to learn from her example to formulate ideas and lead and impel the masses.

[Shelley Walia is the author ofEdward Said and the Writing of History.]

Spread the word