In the United States, a Congressional mandate requires that approximately Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) fill 32,000 beds in immigration detention facilities every day. In Canada, nearly 100,000 people have been detained since 2006.

But for most North Americans, these massive detention facilities are largely invisible. That's by design. The physical architecture of these spaces remain hidden to the general public. With Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention, Toronto-based multidisciplinary artist and migrant rights organizer Tings Chak peels away this invisibility. In graphic novel form, she walks the reader through these physical spaces step by step.

The intricately illustrated book was released by The Architectural Observer last year and I recently got the chance to talk with Chak about the project and her work with Toronto grassroots organizing group No One Is Illegal.

VICTORIA LAW: What made you decide to create this book? Why a graphic novel?

TINGS CHAK: In the fall of 2013, I was struggling through the final year of my architecture degree, finding it really difficult to reconcile my migrant justice organizing life with the schooling I was getting. I knew I wanted to critically examine the spaces of detention as places that are intentionally invisibilized and question the ethics of architectural design of these “undocumented” spaces. To be clear, I am an abolitionist and had and have no intention of proposing a “better” or more “humane” prison. I did, however, want to implicate the people in my discipline who design, construct, and profit from locking up people.

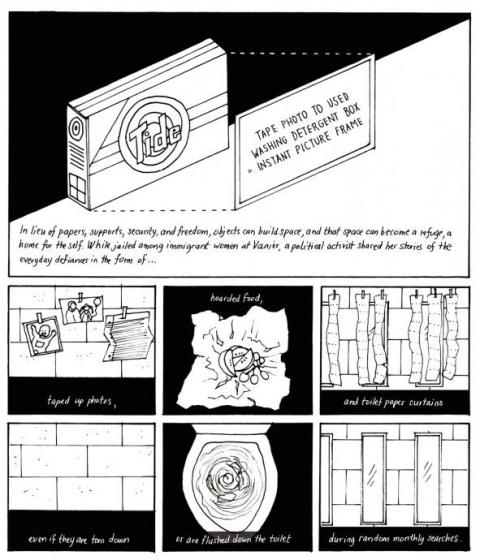

On September 17, fellow No One is Illegal organizers and I got wind of a mass action happening inside Lindsay, Ontario's Central East Correction Centre—191 migrant detainees went on hunger strike. It was the largest action of this kind, which began as a protest of prison conditions but grew into a comprehensive campaign to end immigration detention, first focusing on the practice of indefinite detention. The End Immigration Detention Network was formed. As the stories of resistance emerged, I realized that architecture isn't just about the physical spaces themselves, but the visual stories we tell and representation of these spaces—drawings bring the built form into reality. So I began to draw a generic detention centre, cobbled together from interviews with lawyers and with formerly incarcerated people, architectural design standards, and international guidelines to designing prisons and detention facilities. I focused on the smallest of details to prison landscapes to reveal that at every point in such a space, people are making design decisions to uphold the prison/detention industrial complex.

I decided on the medium of a graphic novel because it's a simple and more accessible way to convey stories than through text alone. The sequential nature of graphic novels means that people can be guided through time and space, and begin to experience what these spaces are like when in real life, access to these spaces is highly restricted. I hoped that the drawings would help reach people's hearts and minds in a way that heavy text pieces and statistics sometimes cannot.

VL: Tell us about migrant detention in Canada.

TC: In Canada, about 100,000 people have been detained since 2006. This includes women, men, and children who do not have immigration status or have precarious status held in one of the three designated federal “holding facilities” and maximum security provincial prisons. All of the facilities are government-run, but there are many private contracts for managing and operating such spaces, including the G4S security firm. Since immigration is not under criminal law, the government justifies jailing migrants for “administrative” purposes, though they are being locked up in the same facilities used for punitive reasons. Perhaps most importantly, migrants are detained without charge or trial—indefinitely. Some have been there for a decade.

Contrary to popular belief, most of the migrants are not coming through the borders through “illegal” means, but rather they come in with immigration status—student, visitor, migrant worker, refugee claimant, or other temporary status—and lose that status based on the restrictive immigration policies. This is to say, people are not “illegal” but they become “illegalized.” As it becomes more difficult for people to obtain permanent residency, particularly poor migrants from the global south, more people are pushed underground. There's an estimated 200,000-300,000 undocumented people who live in my city of 2.5 million people alone.

People come to be entangled in the detention system by carrying out their day to day life. Although Toronto has been a “Sanctuary City” since 2013—meaning that city services should be accessible to all Torontonians regardless of immigration status, without threat of detention and deportation—we still see many cases of people being racially profiled by police, asked for immigration status, and turned over to immigration enforcement at a shelter, food bank, public school, or while taking public transportation. These are experiences of everyday borders and associated fear, which those of us with status take for granted.

VL: What are you hoping that people take away from the book?

TC: At minimum, I hope that a take-away for people is the recognition that immigration detention is a reality and it's all around us. I want people to begin to talk about this reality with people in their lives—I believe this work can slowly shift the hearts and minds of people, and slowly the culture and public discourse on criminalized, illegalized, and racialized people also changes. I also hope that people, through reading this book, come to the realization that prisons are not reformable but are by their very nature oppressive and violent institutions. Finally, I hope that people feel inspired to reflect on their own complicity in this system in very material ways and begin to find their own points of intervention, be it through drawing, through writing, through rallying on the streets, or through any other means.

VC: What kinds of conversations has Undocumented stirred up?

TC: It has been extremely interesting and formative to see what resonates with people, what vocabulary suits each audience as I try to convey the same message: prisons and detention centres should be abolished and we are all in some ways implicated in the prison industrial complex. The book became my entry point to various spaces that I would not usually have access to as an radical activist/organizer. A really interesting moment was at a presentation in Montreal to an art and architecture crowd. It was clear that most people had never even heard of immigration detention and it was clear that I had limited experience in professional practice. But by the end of the hour long presentation, one of the more skeptical of architects started a discussion on how we could abolish prisons. That gives me some hope.

Related Reading: The Rhetoric of Immigration Reform — From "Si Se Puede" to "Bring Them Home."

Victoria Law is a voracious reader and freelance writer who frequently writes about gender, incarceration and resistance. She is also the author of Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women.

Spread the word