Spasms of fear often shake California, a state prey to earthquakes, fires, and floods. One such spasm—a manmade one—is shaking the state today.

Business is down at groceries featuring Mexican and Central American food, and at other stores catering to an immigrant clientele. The possibility of stakeouts by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents has led thousands of Angelenos to abbreviate their daily rounds.

“Since Election Day, children are scared about what might happen to their parents,” says Angelica Salas, executive director of the Coalition for Humane Immigration Rights of Los Angeles. “And parents for their children. We fill out at least ten guardianship letters every day for [undocumented] parents who fear for their [U.S. citizen] kids if they—the parents—are deported.”

The fear is rooted in the grim reality of the new president’s war on immigrants, and in the power that ICE possesses to wage that war. “Sanctuary city, or sanctuary state, is a misleading term,” says State Senate President Kevin de León, who more than any other public official has emerged as the leader of California’s resistance. “It creates the image of an invisible force field you’re safe behind, or reaching home base when you’re a kid playing tag. Actually, that force field doesn’t exist. If you’re undocumented, ICE can pick you up whether you’re in Paducah or liberal Santa Monica.” ICE can and does conduct sweeps in search of undocumented immigrants, and it doesn’t need a warrant to do so.

All of which has made California’s undocumented—about 2.5 million, by recent estimates, fully one million of them in Los Angeles and Orange Counties—and their family members who are citizens, deeply and understandably fearful.

It has also made millions more Californians angry. The Trump crackdown on immigrants has few supporters in the Golden State. In a January poll, the Public Policy Institute of California asked respondents whether they believed “there should be a way for them [undocumented immigrants] to stay in the country legally if certain conditions are met,” or believed instead that “they should not be allowed to stay in this country legally.” Fully 85 percent said they should be allowed to stay, a figure that included 65 percent of Republicans. Asked further if they favored or opposed “California state and local governments making their own policies and taking actions—separate from the federal government—to protect the legal rights of undocumented immigrants,” 65 percent “favored” while just 32 percent “opposed.”

Sentiments like that led to the state’s Trust Act of 2013, which forbade county jails from notifying ICE when releasing undocumented prisoners unless they’d been held or convicted for serious crimes. Sentiments like that have led to a bill currently before (and likely to pass) the legislature that would appropriate state funds to provide potential deportees in immigration court with attorneys. Sentiments like that have led cities up and down the state to forbid their police departments from participating in ICE arrests or inquiring about suspects’, or witnesses’, or anyone’s, immigration status. Sentiments like that have led de León to author another bill before the legislature that would require all local police and jail officials, whether in “sanctuary cities” or not, to devote no state or local resources to working with ICE on any immigration matters. And sentiments like that led thousands of Californians to rush to local airports, unprompted by any organization, to protest ICE’s interdiction of travelers from predominantly Muslim countries.

CALIFORNIA IS THE TRUMP administration’s most formidable adversary, not only on matters of immigration, but on damn near everything. No other entity—not the Democratic Party, not the tech industry, surely not the civil liberties lobby—has the will, the resources, and the power California brings to the fight. Others have the will, certainly, but not California’s clout.

There’s no mystery to the clout. California is immense, a state of 40 million, home to an economy that is the world’s sixth-largest. But the will? Has the home state of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan truly become so overwhelmingly progressive?

It clearly has. What was remarkable about California’s performance in last November’s election wasn’t merely that it went for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump by a margin of four million votes; that’s partly just a testament to the state’s size. What was remarkable was that the share of its voters who cast ballots for Clinton—61.5 percent—was greater than any other state’s.

And this is hardly the only metric that spotlights California as the nation’s most progressive state. California is one of just six states that have a Democratic governor and Democrats in control of both houses of the legislature (California Democrats actually hold two-thirds of the seats in each house). No Republican has been elected to a statewide office (there are ten of them, counting the two U.S. senators) since 2006. In 2012 and again in 2016, state voters have approved ballot measures that made the nation’s most progressive state income tax even more progressive.

Since Jerry Brown became governor in 2011, he and the legislature enacted laws that expanded Medicaid so comprehensively (including a provision that extended it to undocumented minors) that the percentage of uninsured Californians dropped from 19 percent to 7 percent; raised the minimum wage to $15; created the nation’s first automatic retirement plan for workers (who numbered an estimated 6.8 million) whose employers didn’t provide one; registered as a voter every California citizen who showed up to get a driver’s license; set the highest fuel-efficiency standards in the nation; and appropriated $30 million annually for legal assistance for immigrants before Donald Trump was even nominated. Currently before the legislature, with a good chance of enactment, is a bill that would have the state cover all the costs—tuition, room, board, books—incurred by students at the University of California and the California State University system, and another bill, less of a sure thing, that would establish single-payer health care in the state.

Hillary Clinton carried 46 of the state’s 53 congressional districts, including seven represented by newly nervous Republicans. She carried Orange County—ancestral home of the Goldwater Revolution—thereby becoming the first Democrat to do so since Franklin Roosevelt in his landslide victory of 1936. All four Republicans with Orange County districts will face strong challenges in 2018.

Californians know the state’s demographics explain a lot of this change, but only a relative few can tell you what the forces were, and are, that translated the rising number of Latinos and Asians into progressive political power. Both California and Texas, for instance, are 39 percent Latino, but in California, the nation’s most strategically savvy labor movement politically socialized and mobilized the Latino community as Tammany once did the Irish, while Texas, all but devoid of a labor movement, has seen no such development. California’s fast-growing Asian communities, which constitute nearly 15 percent of the state’s population, have moved left in recent decades, with more than 70 percent of their vote going to Democrats in recent elections. Add the Latinos and Asians to the state’s African American population and the large number of white liberals in the state’s metropolitan centers, and California’s newfound status as the nation’s leftmost state should come as no mystery. Indeed, among the world’s six largest economies—the United States, China, Germany, Britain, France, and the Golden State—California’s citizenry and elected leaders are clearly the most progressive.

And they have the wherewithal, along with the will, to fight the Trump administration on climate change, social insurance, immigrant rights, and much else.

PRESIDENT TRUMP HAS journeyed to Detroit and announced that the fuel emissions standards put in place by his predecessor—initially California’s standards, which the Obama administration then decided to adopt nationally—were job killers. He pledged that his new man at the Environmental Protection Agency, Scott Pruitt, would scrap them.

But Pruitt can’t scrap them for California, or for the 13 other states that adhere to California’s standards. Unless Trump means to revoke the waiver that permits the state to have higher standards than the feds, 40 percent of the domestic auto market will still have those tighter standards.

California’s unique legal standing in matters of clean air and climate change began, of course, as a response to Los Angeles’s eternal battle with smog. The state started regulating tailpipe emissions in 1966, and when the federal government first enacted the Clean Air Act in 1970, it allowed California, and only California, to set its own clean air standards so long as they were stricter than the feds’. In 1977, the law was amended to permit other states to adopt California’s standards, too.

In 2002, California augmented its concern over the quality of gas and emissions with concern for their quantity. Worried by climate change and the fossil fuel emissions that were speeding that change, the state passed a law limiting auto emissions by demanding stricter fuel-efficiency standards—and those 13 other states, thanks to that 1977 amendment, adopted those standards as well.

Over the years, the EPA has granted California about 100 different waivers, but the George W. Bush administration denied the one for increasing fuel efficiency to curtail climate change. California took Bush’s EPA to court, and the case was still in progress when Barack Obama became president and the EPA granted the waiver. More than that, as a condition for the 2009 auto bailout, and then again in 2012, Obama got the car companies to agree to his EPA’s standards, which the EPA had written to match California’s.

Trump’s announcement, then, did nothing to affect California’s standards; indeed, California was a signatory to the 2012 agreement and its deal with the auto industry is still in place, as, presumably, are those of the other states. To negate California’s accord, Trump’s EPA would have to revoke its waiver that permitted California to set its standards. That would be breaking new legal ground, as the EPA has never before attempted to revoke a waiver.

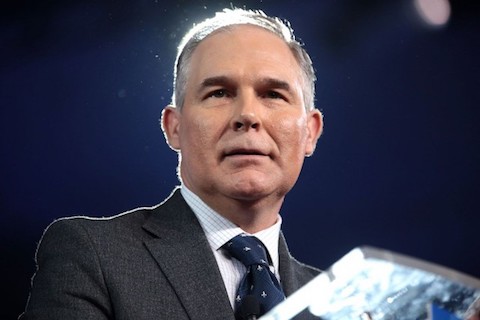

In order to undo California's ambitious fuel emission standards, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt would need to convince a federal court to revoke a waiver that has allowed the state to surpass federal standards since 1970. Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons

The problem for Trump and Pruitt, says Ann Carlson, a professor of environmental law at UCLA, is that “to be effective, to give the automakers what they want, the only way is to roll back the California waiver.” For now, that’s apparently a bridge too far for Trump’s EPA, though there’s no telling what it may do later. It’s already too late to roll back the first set of stricter standards, due to be in place by 2018, since the auto industry has already made the investments to meet those specifications. It’s not until 2022 that the next set of still stricter standards are supposed to take effect, so Trump and Pruitt have some time before they decide whether to revoke the waiver and be taken to court.

Such a case, says Carlson, would be heard in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, which currently has a majority of Democrat-appointed judges. It’s not clear it could even advance to the Supreme Court, since, as Carlson says, it poses statutory rather than constitutional questions. But if it were to advance, the deciding vote might be Anthony Kennedy’s—who’d have to decide whether to vote as a Republican or a Californian.

Even if Trump were to revoke the waiver and prevail in court, California would still have one legally unassailable option: Placing a much higher sales tax on new cars and trucks that fail to meet what would have been the state’s standards than the tax on cars that do meet those standards. California’s market share is so large that this might compel Detroit to still turn out more efficient cars. “We’re at least 10 percent of the national market,” says one state air quality official, “and 10 percent matters to manufacturers. When we’ve set efficiency standards before, the manufacturers have made a product to match those standards.” And once they go to the trouble of making those products, they just might make more to sell to buyers across the nation.

THE BIGGEST HIT THAT California might have to take from the White House and the Republican Congress would be an attack on Medicaid. Because the state has used the law’s discretion to extend Medicaid (which in California is called MediCal) to as many eligible recipients as possible, fully 14 million Californians get their health coverage through the program—about one-third of the state. Roughly 20 percent of all Americans on Medicaid are Californians.

“Prior to the ACA, we ranked sixth among the states in the percentage of uninsured,” says Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California. “But no other state had as big a reduction in the number and percentage of uninsured as we did.” California extensively marketed the programs, and did automatic enrollments of food stamp recipients. “We have the uninsured rate down to 7 percent now, and are making progress toward universality,” Wright adds. “But if the Ryan plan is enacted, we could be set back for an entire generation.”

Some of the highest rates of Medicaid coverage are found in California congressional districts represented by Republicans—particularly in agricultural areas of the Central Valley. “Half of [GOP Representative David] Valadao’s 800,000 constituents are on Medicaid,” says Wright, adding that Valadao’s district was carried by Clinton. “The percentage of residents on Medicaid in Kern County is 45; in Fresno, 50; in Tulare, 55. Cutting back Medicaid in the Central Valley would affect half those Republicans’ constituents; you’d see closures of hospitals that serve everyone.”

Chris Hoene, executive director of the California Budget Project, estimates that the cuts to California Medicaid funding in the Ryan bill would come to between $7 billion and $10 billion. Could the state make that up by raising its own taxes?

The problem with that is that the voters just approved more high-end tax hikes, along with a higher tobacco tax, in November. “We already have the highest income tax rates on high earners of any state,” says Wright. “If the differential between us and other states is 5 or even 10 percent, they’re not likely to move, but if it’s 30 percent? Nobody knows.” Other options include a sales tax on services, or a repeal of Proposition 13’s limits on property taxes, at least for commercial properties, which might go on the 2018 or 2020 ballot. It’s been holy writ in California for decades that voters would never tamper with Proposition 13. Whether massive cuts to state services would make a difference is anybody’s guess.

A more plausible option might be to enact a state estate tax, which California tax expert (and occasional American Prospect contributor) Roy Ulrich estimates could bring in as much as $4 billion annually. California once had an estate tax of its own, but voters abolished it in 1982, at the height of Proposition 13 tax-cutting mania. Democratic State Senator Scott Wiener has announced he’ll try to put a measure on the 2018 ballot that will recreate such a tax if, and only if, the Trump administration follows through on the president’s vow to repeal the federal estate tax. Wiener’s proposal (and Ulrich’s idea) is to set its rates identical to those in the federal tax, so that heirs to wealthy estates would be paying the same amount—only to Sacramento rather than Washington. If enacted, the state could use those funds to keep more Californians on Medicaid—and set some aside for cities whose police departments and jails lose funding as a result of Trump’s attack on sanctuary cities and states.

One other aspect of California’s social insurance that’s under attack in Washington is the state’s automatic retirement set-aside program, that’s scheduled to go into operation next year. As crafted by de León, the program requires employers who don’t offer retirement benefits to automatically deduct a small portion of their employees’ paychecks to be invested in a state-run retirement investment fund, unless the employees opt out of the program. De León had to persuade President Obama and Labor Secretary Tom Perez to alter federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act regulations to make the program legal. (“And we’d like to have created an employer contribution, too, but that required an act of [the Republican-controlled] Congress,” de León says.)

Since the current Congress convened, a number of Republican members have suggested it should alter the ERISA regulations to keep the program from going into effect. Their actions have been prompted by major banks and other financial institutions that offer retirement programs of their own.

“This is going to be the largest expansion of retirement security since 1935,” says de León. “We’ve created a new market for people left out of the existing system. It doesn’t take a market away from Wall Street. But Wall Street doesn’t like that it will charge lower fees than they do.”

Congress has yet to act on the GOP proposal—which would not only scuttle California’s plan, but those that other states adopted once the ERISA regulations were altered.

ON A WIND-WHIPPED SATURDAY in late February, a crowd of undocumented immigrants and their families, about 700 in all, have come to Los Angeles Trade Tech, a community college in downtown L.A., to learn what they can do to fight deportation. Convened by de León, the “Know Your Rights” forum features attorneys talking one-on-one with worried Angelenos. It also features County Sheriff Jim McDonald and Deputy L.A. Police Chief Robert Arcos, who both assure the crowd that their officers will not participate with ICE in any investigations or arrests, or inquire about anyone’s immigration status. “We know you’re suffering from fear, anxiety, and distrust of law enforcement,” Arcos says, “but know that your LAPD is here to serve and protect you.” The crowd greets this bit of what is normally pro forma boilerplate with cheers.

Several of the speakers are immigrant-rights attorneys, including the dean of the Los Angeles immigrant-rights bar, Peter Schey. “When people know their rights, they will not be deported,” Schey begins. “If ICE is at your door, you have the right not to let them in unless they have a court order. You have the right to remain silent—99 of 100 deportations are due to statements made to agents at the time of arrest. They will not have any evidence against you if you remain silent. Silencio! Silencio! Does everybody understand that?”

“Yes!” the crowd responds.

Much of California’s civil society has rallied to the immigrants’ defense. The Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, a body of 300 local unions, has formed a rapid-response team that will offer financial and other forms of assistance to families whose breadwinners are detained or deported. The federation’s Miguel Contreras Foundation (named after the late labor leader who turned the city’s labor-Latino alliance into L.A.’s most formidable political organization) has assembled a group of more than 100 private attorneys who will work pro bono or “low-bono” for undocumented immigrants in deportation proceedings. “The question before us,” says Rusty Hicks, the federation’s executive secretary-treasurer, “is how do we make this different from 1942, when Japanese Americans were carted away and no one lifted a finger.”

In 2006, when immigration reform was before Congress, an estimated one million people, the vast majority Latino, filled Wilshire Boulevard for miles in support of legal status. Eleven years later, in much more dire circumstances, SEIU and its many allies are hoping for a similar turnout—this time bringing together not just Latinos and immigrants, but the Angelenos who turned out for the Women’s March as well. That kind of turnout wouldn’t alter federal policy, but it would at least display Californians’ support for immigrant families.

Thousands of Californians are already working to do the one thing that would alter federal policy: Cow Republican members of Congress to heed the better angels of their nature (that is, oppose Trump’s immigration crackdown, Ryan’s gutting of health coverage, and the thousand other unnatural shocks the GOP is promoting), and defeat them come 2018. Of the seven California GOP House members whose districts Clinton carried last November, two come from Central Valley districts that are home to hundreds of thousands of Medicaid recipients. Four hail from Orange County, including Darrell Issa, who eked out the narrowest of victories last November, winning by a scant 1,600 votes. Fully aware of the approaching political storm, Issa has called for a special prosecutor to investigate Trump’s Russian connections, and said he’s not committed to voting for Ryan’s bill.

On a late February evening, I travel to Fullerton in the heart of Orange County to attend one of the five town-hall-without-the-member-present meetings that Indivisible had called in the district of Ed Royce, a GOP congressman who has flown beneath the public’s radar since he was first elected in 1992. Clinton carried Royce’s district by 8.5 percentage points, and the 150 attendees, many of them never politically active before, hope that margin means Royce can be beat next year.

The side room of a Sizzler steakhouse is packed, even though the meeting was called just two days previous. It’s largely a white middle-class gathering, with some longtime Democratic activists, League of Women Voters stalwarts, and staunch progressives making up perhaps half the attendees. They’re not really representative of the district, which is one-third Latino, one-third white, and one-third Asian, including a large Vietnamese community that has long voted Republican, like most refugees from communist countries. Like Cuban Americans, however, the children of Vietnamese refugees have been voting more Democratic, and the grandchildren, overwhelmingly so.

The Indivisibles are eager to join up with groups that may be new to them and come from other parts of the progressive cosmos. Many sign up for a candlelight vigil the next night outside Royce’s home, an event sponsored by the largely Latino SEIU Orange County janitors’ local union. A number also register for precinct walks planned for the day following by Knock Every Door, a group staffed in California by veterans of Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign.

Middle-class white liberals, a mobilized Latino community, left-moving Asian Americans, a powerful environmental community, a uniquely vibrant union movement, a tech sector willing to fund at least some anti-Trump campaigns, women coming forth as candidates, properly enraged millennials, and some deft political leaders—these are the pillars of the California resistance. Together, they form Trump’s most potent opponent.

This article appears in the Spring 2017 issue of The American Prospect magazine. Subscribe here.

Spread the word