FOR ALMOST four years now, I have worn a shirt bearing the legendLibertad Oscar López Rivera Ahora. This portable messenger was a parting gift from a Puerto Rican family whose vacation cabin abutted ours on a beach on the island of Culebra; my wife befriended them one night, and we were, much to our delight, taken in as honorary family members. It was the first I had heard of Oscar López Rivera. On rare occasions, someone — a Puerto Rican student in a political philosophy seminar, a graduate student in a university library, a Puerto Rican family in Brooklyn — recognizes and acknowledges the man on the shirt and offers me congratulations. Perhaps the Spanish inscription — an epiphany of otherness — places him in a greater anonymity than the one he already suffers.

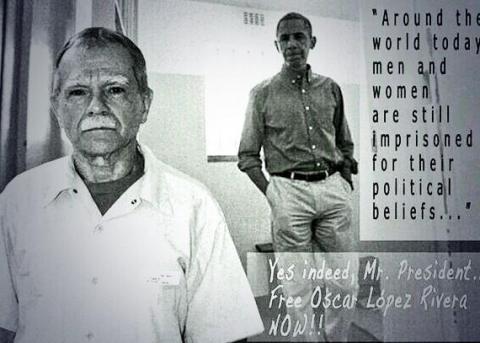

Oscar López Rivera is undeservedly the most obscure of American political prisoners. A former member of the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN), a clandestine paramilitary organization that advocated political independence for Puerto Rico, López Rivera is serving the 34th year of a compounded 70-year sentence for seditious conspiracy plus conspiracy to escape. He was offered clemency by President Bill Clinton in 1999, but rejected it. Now 72 years old, he remains in a federal prison. López Rivera’s imprisonment, just as his homeland’s political status, remains a mystery to most Americans. But they, and his refusal to accept clemency, entail a political and moral crisis that cannot be looked away; his case and the history that backgrounds it force a searching reexamination of what it means to be American. López Rivera reminds Americans of a colonial and imperial past whose contours are still visible. Despite a stingy record for commutations and pardons, President Barack Obama could and should use his constitutional powers to commute Oscar’s punitive sentence and grant his immediate release.

For the past few years, the Cabanillas of Houston, a successful middle-class immigrant family, proudly Puerto Rican, have made López Rivera’s release their enduring cause. The Cabanillas’ campaign joins the tireless work of Puerto Ricans on behalf of their political prisoners, for every decade since 1898 has seen independentistas in prison. Those on the “outside” have persisted in fighting for their rights and their freedom. These struggles have led to US presidents commuting sentences of Puerto Rican political prisoners: Harry Truman commuted the death sentence of Oscar Collazo in 1952; Jimmy Carter commuted the sentences of Nationalist Party prisoners in 1977 and 1979; and Bill Clinton did the same with the sentences of López Rivera’s codefendants in 1999. Some of the activists who worked on those campaigns still work to free López Rivera. They include the human rights group Comité Pro Derechos Humanos and the People’s Law Office; they helped create the environment into which the Cabanillas family entered. Their combined efforts and commitment to free López Rivera have elevated his struggle to American consciousness; they have compelled me to write this essay.

La Isla Bonita

Puerto Rico has been a US possession since it was “acquired” — in the usual colonial fashion, through armed disputation — from Spain in 1898. Puerto Ricans became US citizens in 1917, just in time for 20,000 “Boricuas” to be drafted to serve in World War I. Almost a century later, Puerto Ricans living on their island are not allowed to vote in presidential elections; Puerto Ricans have attained neither statehood nor independence. Along the way, they have suffered the indignity of a ban — imposed in 1948 — on owning a Puerto Rican flag, singing a “patriotic song,” or advocating for independence. Their curious political status, a “United States territory,” which is not a state, but whose residents are given automatic US citizenship, ensures economic and political exploitation by the “mainland.” Today, Puerto Rican demands for full political and legal rights resurrect a debate whose most radical form is a fading memory.

During the 1960s and ’70s, young Puerto Ricans in the US — inspired by the global anticolonial and national liberation movements that gave those decades their most distinctive political imprint — railed against the terrible triad of colonialism, racism, and exploitation embodied in American sovereignty over Puerto Rico. Even as young Americans — including López Rivera, who had moved to Chicago as a teenager — were drafted for the war in Vietnam, the discourses and actions of Puerto Rican independentistascontinued in the US. On returning from Vietnam — where he earned a Bronze Star for his service — López Rivera plunged into the political activism and community actions then underway in his Chicago Latino neighborhoods; he founded cultural centers and high schools, and, as a community organizer, helped establish rehabilitation programs for drug addicts and prisoners.

Armed clandestine political organizations — like FALN, one among many that had sprung up in Puerto Rico — represented one pole of Puerto Rican political movements; its tactics — which did not eschew violent direct action — placed it a rung higher in the ladder of political escalation. Between 1974 and 1983, FALN claimed responsibility for over a hundred bombings of military, government, and economic targets in and around Chicago and New York, which caused the death of six and injuries to dozens (there were no deaths or injuries in Chicago-area bombings). FALN’s bombings — accompanied by demands for the release of fellow independentistas serving sentences in US prisons for their activism in the 1950s — starkly highlighted Puerto Rico’s colonial status; they informed the US it was viewed as a malignant occupier in zones it might have imagined national territory. These bombings did not lack justification as self-defense: the infamous 1975 bombing of the Fraunces Tavern in New York, for instance, was a direct and explicitly identified response to the January 11, 1975 bombing in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, where a CIA-trained operator detonated a bomb causing the death of two independentistas and a child and severely injuring ten others. In modern parlance, FALN was a “terrorist” group. They were treated accordingly.

In 1980, 11 men and women, allegedly members and leaders of FALN, were arrested and charged with seditious conspiracy — to oppose US authority over Puerto Rico by force — and related charges of weapon possession and transporting stolen cars across state lines. López Rivera was named codefendant in the indictment. The accused — after being tried in a Federal District Court — were given prison sentences ranging from 55 to 90 years. Judge Thomas McMillen regretted not being able to give them the death penalty.

In 1981, López Rivera was arrested after a traffic stop, and after being tried, was sentenced — again by McMillen — to a prison term of 55 years. Like his other codefendants, he was not charged with participating in FALN bombings that caused loss of life (though one prosecution witness testified that López Rivera had taught him how to make bombs). In 1987, López Rivera was sentenced to an additional 15 years for conspiracy to escape; in shades of the modern FBI entrapment of young Muslims in the US, this was a plot conceived and carried out by government agents and provocateurs.

In 1981, the average federal sentence for murder was 10 years; in 1987, the average sentence for an actual escape from prison was less than two years.

The Dangers of Sedition

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 remain a blot on American democracy; John Adams deeply regretted — till the day of his death — being their prime mover. The crimes they charge citizens with — and the notion of a political dissident imprisoned for holding political beliefs supposedly dangerous — are an embarrassment for democracies. The very idea of sedition induces puzzlement in a student of politics: how can a liberal democracy punish the entertainment of beliefs? The contemporary illegitimate child of those Acts, the charge of seditious conspiracy (18 U.S.C. § 2384), which indicts American citizens for planning to revolt in concert with others, was conceived during the Civil War but, in actual application between the 1930s and 1980s, only found one target: Puerto Rican nationalists.

The accusation of seditious conspiracy is political: nothing enrages the patriot like the seditionist. He is a fifth columnist, a cancer on the body politic. The seditionist assaults the idea of the nation and offends our sensibilities by proclaiming that our idols have feet of clay. Sedition incites rebellions by encouraging citizens to rise up against their state; the existence of the seditionist is a threat to the public and psychic order underwritten by nationalist sentiment. In the old days, those who spoke against dominant paradigms, who placed the earth at the center of the universe and the like, were tortured, torn apart by mobs, burnt at the stake.

Unsurprisingly, we find religious fervor in the prosecution of this variant of political heresy. Nietzsche described the punishment felt suitable for this kind of citizen as:

A declaration of war and a war measure against an enemy of peace, law, order, authority, who is fought as dangerous to the life of the community, in breach of the contract on which the community is founded, as a rebel, a traitor and breaker of the peace, with all the means war can provide.

The seditionist is a preacher too; he seeks to convert, to include others in his cult. These are made more sinister by the application of the term “conspiracy”: concerted planning with those of like minds. Ideally, a seditionist would be exiled or killed; the next best option is removal from public sight.

At his trial, López Rivera — invoking international law — asserted that the US colonization of Puerto Rico was a crime against humanity. This language hearkened uncomfortably to the 20th century’s worst excesses. López Rivera thus declared himself a combatant in an anticolonial war to liberate Puerto Rico and invoked prisoner of war status. He noted that courts of colonial powers are prohibited from criminalizing anticolonial struggle. He also asserted that US courts had no jurisdiction to try him as a criminal; by rejecting their legitimacy, he placed himself in fundamental opposition to the United States, a nation of laws. Most insultingly, he demanded remandment to an international court and turned away from the blessings of the American republic, preferring the justice of the unexceptional world to the injustice of the exceptional nation. He presented no defense — he did not disavow his activities — and pursued no appeal. Like other Puerto Ricanindependentistas in US prisons, López Rivera became a political prisoner, punished for political beliefs and associations.

Political prisoners are inviting targets for rhetorical and physical abuse. This process began when López Rivera received the scorn and the open dislike of the trial judge. Then, over the years, he was described — by the US law enforcement agencies, the FBI, the Bureau of Prisons, and the Parole Commission — as a “notorious and incorrigible criminal,” “a predator,” and “the worst of the worst.” This rhetoric served as precursor to, and accompanied, torture. López Rivera was transferred to maximum security prisons where for 12 years he was subjected to solitary confinement and sporadic sleep deprivation. “Torture” is a term that should make Americans uncomfortable, but in these post-9/11 days it does not; we have been instructed it is necessary to preserve the nation state, a village that needs burning to protect it.

All torture is refined by its perpetrators; López Rivera’s captors are no exception. In 1998, after a dozen years in isolation, he was required to report every two hours to prison guards. This situation was to last 18 months. It has lasted 17 years. His cell was constantly searched, his reading and art materials confiscated and destroyed, and visits from family stopped. López Rivera’s speech was placed under totalitarian control: for almost 20 years, the Federal Bureau of Prisons — unsurprisingly claiming “security” concerns — denied media requests for interviews before relenting in 2013 to allow telephone interviews. The censorship still applies to in-person and on-camera interviews. These bans reek of governmental insecurity; they speak of a state afraid to hear its prisoner’s voice.

In 2011, at his parole hearing, a chained and handcuffed López Rivera heard live testimony from a wounded survivor and family members of the victims of the Fraunces Tavern bombing. Their cascade of vitriolic testimony ensured that he was not released. But López Rivera was never accused or convicted of actions related to the Tavern bombing; the testimony’s service as a basis for the parole commission’s denial of parole was a legal atrocity. His parole is due for reconsideration in 2026, when he will be 83 years old. The United States’s tactics worked: they “disappeared” López Rivera.

In 1999, Bill Clinton commuted the sentences of some of López Rivera’s codefendants and offered a conditional release to López Rivera: that he serve an additional 10 years in prison. López Rivera turned it down; he would not abandon his codefendants, Carlos Alberto Torres and Marie Haydée Beltrán Torres, not included in the clemency offer. López Rivera’s refusal to accept commutation not extended to his partners was a defiant act of political solidarity and a protest against the illegality of his sentence. With these gestures, he ensured a continuance of the struggle that brought him to jail in the first place; the symbolic weight of his incarceration pressed down heavier on American consciousness.

The Cabanillas

By 2011, Fernando Cabanillas was enjoying the fruits of a long and successful career as a clinical and academic oncologist specializing in the treatment of lymphomas at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. After moving back to Puerto Rico, his work as director of the Auxilio Mutuo Cancer Center in San Juan left him little time for politics. His daughters Maru and Marian had found successful careers in Houston; his teenage grandson Raul gave him ample joy. His wife Myrta and he looked forward to their mellow golden years, to be spent enjoying the company of their tightly knit family. But their peace had been disturbed by news of López Rivera’s continuing imprisonment, then entering its fourth decade.

The Cabanillas first read López Rivera’s story in a local newspaper article about a political prisoner in jail for three decades. By then, the fervor of the ’70s’s struggles had died down; following the 1999 clemencies, supporters of the independentistas had focused on welcoming López Rivera’s codefendants home, ensuring their housing, employment, and medical care. The campaign for their release and the efforts to welcome them had been embraced by civil society beyond the independence movement. But rhetorical barrages from the mainland against statehood and independence — and political inaction — meant Puerto Rico’s ambiguous positioning in the American republic was increasingly cemented. Puerto Rico’s fate was a fait accompli; its younger generations knew little of the struggles that animated López Rivera.

López Rivera’s cause, and the length of his sentence, galvanized the Cabanillas into an escalating series of actions. Fernando and Myrta had brought up their children and grandchildren with their inclusive antiracist politics. It was easy to enlist them as allies. The Cabanillas — father, mother, daughters, and grandson — began in the simplest of ways: telling others, family and friends included, about the tale of López Rivera, and later, designing, wearing, and distributing T-shirts and wristbands with slogans (and gifting them to new friends like me). These forms of consciousness raising were, as they well knew, of only limited efficacy. Early in 2013, as the 32nd year of López Rivera’s imprisonment rolled around, Fernando enlisted a cousin, Sonia Cabanillas, a professor of humanities at Universidad Metropolitana, and her husband Nick Quijano, an artist of considerable standing in Puerto Rico’s art world, and invited them for a brainstorming weekend meeting in Ponce. Myrta suggested a symbolic imprisonment where supporters of López Rivera’s excarceration would take turns being locked into a mock cell — one possessing the measurements of his actual holding location. Quijano, also an architect, volunteered to design and build two cells to scale.

The Cabanillas now moved from informal support to a formally organized stance. The group “32 x Oscar” was founded: it represented 32 people, one for each year Oscar had spent in jail. Their first action — on the 32nd anniversary of Oscar’s imprisonment — was to symbolically imprison themselves for 24 hours in the Puerto Rican capital, San Juan. Comité Pro Derechos Humanos suggested islandwide actions in five cities, a suggestion adopted with alacrity. Word of the symbolic imprisonment spread; the 45 minute shifts per protester — including ones at late night and the earliest hours of the morning — were quickly claimed. The vigil began at midnight on May 29, 2013; the first prisoner in San Juan was Mayra Montero, a journalist with Puerto Rico’s largest newspaper, El Nuevo Día. By noon, the Plaza de Armas was packed. The enthusiasm was visible and palpable. Incredibly enough, Fernando received a call from the Puerto Rico Senate asking if the president, Eduardo Bhatia, could take a shift. Soon, a call came from the personal assistant of popular artist and composer of hip hop and urban-style Latin-American music René Pérez Joglar — better known as Residente of Calle 13 — informing Cabanillas of his desire to “imprison” himself with his wife and family. Pérez Joglar, a creator of socially and politically conscious music, and winner of 22 Latin Grammy Awards and three Grammy Awards, was an ideal ally. Soon, the best of all problems posed itself; thanks to increasing demand, “32 x Oscar” could not allot 45-minute shifts per prisoner. It began assigning five minute blocks and allowed group occupancy of the cells. The decades-long campaign to free López Rivera had been reinvigorated.

As president of “32 x Oscar,” Fernando also organized a march in San Juan in which 50,000 people — including US members of Congress Luis Gutiérrez and Nydia Velázquez, who flew down from Washington — participated. The group’s next event — in keeping with its flair for political rhetoric — was termed “Al Mar x Oscar”: dozens of kayaks and boats welcomed a cabezudo(large papier-mâché head) of López Rivera landing in Puerto Rico in a boat. This symbolic homecoming was a masterpiece of political theater. “32 x Oscar” also directed pleas to Pope Francis, asking him to raise López Rivera’s case in his meeting with President Obama; it organized presentations at the international congresses of the Parlamento Centroamericano (PARLACEN) where Clarisa, López Rivera’s daughter, presented his case and received a standing ovation and a unanimous resolution in support.

The Cabanillas’ struggle also includes traditional letter writing. In a letter to Barack Obama, Fernando noted that Nelson Mandela, much admired by the president, spent 27 years in jail for seditious conspiracy. He also noted that Obama’s own father, Barack, and paternal grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama, were guilty of clandestine political activity when they participated in Kenya’s anticolonial struggle for independence from the British Empire. These acute parallels and analogies should induce discomfort in those who could, and should, care.

Today, Puerto Ricans remain torn over which alternative — independence from the United States or integration into it via statehood — would be a more desirable political objective. But Oscar López Rivera’s release unites these viewpoints. When Fernando recently asked Puerto Rican youngsters if they knew who Oscar López Rivera was, back came the quick answer: “the guy imprisoned in the US.” For Fernando, López Rivera’s story speaks of a “pathetic and dreadful injustice” to a “fellow Puerto Rican” and engenders a “duty” to “redress” it. The values that animated the Cabanillas’ raising of their children suffuse their present struggle, in support of a man they have never met or personally known. For the Cabanillas, López Rivera’s death in jail would be a tragedy, one they will not “allow to happen.” Their fellow Americans should not either.

Puerto Rico Today

The US, ever eager to proclaim political prisoners are incompatible with democracy, shows little inclination to act in a case that cuts dangerously close to its political jugular. It continues to deny it has political prisoners; those it detains are just criminals. As López Rivera notes, this denial performs several functions: it serves to “cover up the nefarious, barbaric and even criminal acts and practices it carries out against ”; it serves as “license to violate basic human rights by subjecting us to isolation and sensory deprivation regimens”; it serves to “hoodwink its own citizens to believe that it doesn’t criminalize dissenters”; it serves to “perpetuate the lie that it is the ultimate defender of freedom, justice, democracy and human rights”; and it serves to “criminalize the political prisoners and to disconnect us from our families, communities, supporters and the just and noble causes we served and try to continue serving.”

The blindness this denial creates need not be ours. Americans should not look away from this moral and political atrocity perpetrated in their name. We should not be collaborators. Like Fernando Cabanillas and his family, we should look closer. ¡Libertad para Oscar López Rivera Ahora! should not be chanted only by Puerto Ricans; it should be on the lips of all those who believe in justice.

¤

Author’s Note: I would like to thank Fernando Cabanillas and Jan Susler (Oscar’s lawyer, from the People’s Law Office) for their assistance in writing this essay.

¤

Spread the word