One hundred fifty years ago today, the U.S. Army took possession of Galveston Island, a barrier island just off the Texas coast that guards the entrance to Galveston Bay, and began a late-arriving, long-lasting war against slavery in Texas. This little-known battle would endure for months after the end of what we normally think of as the Civil War. This struggle, pitting Texas freedpeople and loyalists and the U.S. Army against stubborn defenders of slavery, would become the basis for the increasingly popular celebrations of Juneteenth, a predominantly African-American holiday celebrating emancipation on or about June 19th every year.

The historical origins of Juneteenth are clear. On June 19, 1865, U.S. Major General Gordon Granger, newly arrived with 1,800 men in Texas, ordered that “all slaves are free” in Texas and that there would be an “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.” The idea that any such proclamation would still need to be issued in June 1865 – two months after the surrender at Appomattox – forces us to rethink how and when slavery and the Civil War really ended. And in turn it helps us recognize Juneteenth as not just a bookend to the Civil War but as a celebration and commemoration of the epic struggles of emancipation and Reconstruction.

By June 19, 1865, it had been more than two years since President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, almost five months since Congress passed the 13th Amendment, and more than two months since General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate army at Appomattox Court House. So why did Granger need to act to end slavery?

To answer that question, we have to look back at slavery, the Civil War, and Texas’ peculiar place in both histories. During the Civil War, white planters forcibly moved tens of thousands of slaves to Texas, hoping to keep them in bondage and away from the U.S. Army. Even after Lee surrendered, Confederate Texans dreamed of sustaining the rebel cause there. Only on June 2, 1865, after the state’s rebel governor had already fled to Mexico, did Confederate Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith agree to surrender the state. For more than two weeks, chaos reigned as people looted the state treasury, and no one was certain who was in charge.

In that chaos, many African-Americans fled, some across the river in Mexico, a less-remembered pathway to freedom in the decades before the Civil War. Others launched strikes or refused to work. But in a state where whites outnumbered slaves more than two-to-one, planters and ranchers did everything in their power to sustain slavery wherever they could.

Granger’s arrival on June 19 marked the first effective intervention of the United States in Texas on the side of ending slavery. So when Granger issued his proclamation in Galveston, it was no abstract or symbolic statement against slavery and rebellion; he was striking a blow against slavery itself in the place where it remained most firmly entrenched in June 1865.

But what did Granger’s proclamation mean? One oft-told myth has it that Texans simply did not know that slavery had ended. What Granger brought, in this telling, was good news. But if we listen to the words of someone like Felix Haywood, a slave in Texas during the Civil War, we see that this was not so. “We knowed what was goin’ on in [the war] all the time,” Haywood later remembered. At emancipation, “We all felt like heroes and nobody had made us that way but ourselves.”

If Haywood and other enslaved people knew about the Emancipation Proclamation, what exactly did the events of June 19, 1865 mean? Here we face a key forgotten reality about the end of the Civil War and slavery that has been shrouded in the mythology of Appomattox. The internecine conflict and the institution of slavery could not and did not end neatly at Appomattox or on Galveston Island. Ending slavery was not simply a matter of issuing pronouncements. It was a matter of forcing rebels to obey the law. To a very real extent, the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment amounted to promissory notes of freedom. The real on-the-ground work of ending slavery and defending the rudiments of liberty was done by the freedpeople in collaboration with and often backed by the force of the US Army.

Granger’s proclamation may not have brought news of emancipation but it did carry this crucial promise of force. Within weeks, fifty thousand U.S. troops flooded into the state in a late-arriving occupation. These soldiers were needed because planters would not give up on slavery. In October 1865, months after the June orders, white Texans in some regions “still claim and control as property, and in two or three instances recently bought and sold them,” according to one report. To sustain slavery, some planters systematically murdered rebellious African-Americans to try to frighten the rest into submission. A report by the Texas constitutional convention claimed that between 1865 and 1868, white Texans killed almost 400 black people; black Texans, the report claimed, killed 10 whites. Other planters hoped to hold onto slavery in one form or another until they could overturn the Emancipation Proclamation in court.

Against this resistance, the Army turned to force. In a largely forgotten or misunderstood occupation, the Army spread more than 40 outposts across Texas to teach rebels “the idea of law as an irresistible power to which all must bow.” Freedpeople, as Haywood’s quote reminds us, did not need the Army to teach them about freedom; they needed the Army to teach planters the futility of trying to sustain slavery.

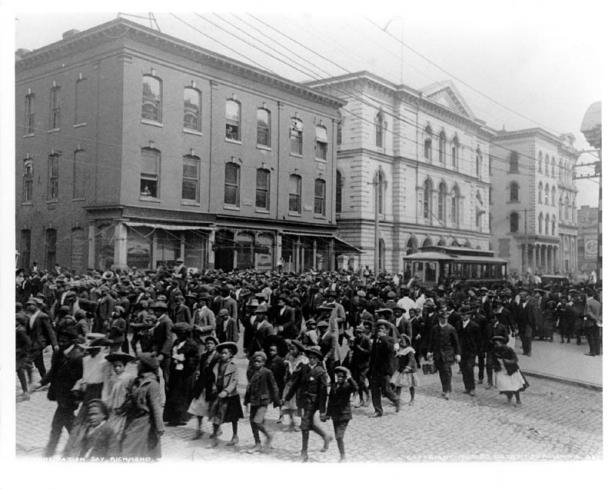

Emancipation Day Celebration, June 19, 1900. Photo from Grace Murray Stephenson. Public domain from the University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, from ...MORE

Against that resistance, and in response to freedpeople’s complaints, the Army acted as if the Civil War had not in fact ended. Relying upon its broad war powers to exert control over civilians, the Army attacked slavery by arresting judges and sheriffs, taking control over court cases, running military commissions, and suspending habeas corpus. As Texas’ provisional governor—a white loyalist—tried to build a new state, the Army provided crucial support against a developing insurgency.

Slowly, slavery itself ended. By the winter of 1865-1866, freedpeople, the Army, and white loyalists had extinguished the ‘peculiar institution’ in Texas. Under the threat of continued military occupation, President Andrew Johnson coerced former Confederate states into inscribing this change into the Constitution by ratifying the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

But the victory over slavery was only one in a series of battles to determine the meaning of freedom. Over the next few years, freedpeople’s rights and their power expanded, along with the Army’s authority to protect them. Responding to planters’ efforts to create a hardened racial caste system and to freedpeople’s testimony, the U.S. Congress in 1866 tried to create defensible rights through the 14th Amendment that created birthright citizenship, established equal protection under the law, and guaranteed due process. When rebel states did not accept that amendment, Congress reasserted military control and charged the Army with registering freedpeople to vote. In 1869 Congress also passed a 15th Amendment prohibiting denial of the vote on grounds of race or previous condition of servitude. New biracial governments in the South helped write both amendments into the Constitution, thus remaking basic rights not just for African-Americans but for all Americans.

Reconstruction created a new world in Texas. Almost 40,000 black Texans, mostly former slaves, voted to call the state’s new constitutional convention. The new state government in Texas, as elsewhere, established statewide public schools, protected small homesteads from foreclosure, and created a tri-racial state police. Among the leading black politicians to emerge were freeborn teacher George T. Ruby and the previously enslaved Matthew Gaines. On the ground, freedpeople built vibrant families, constructed churches, opened schools, and elected African-Americans to less-remembered but crucial local offices.

But these gains did not endure. Over the 1870s, as the Army lost its hold on many rebel states, Democrats re-established control. Through a poll tax in 1902 and an all-white primary in 1903, African-American voter turnout in Texas dropped from about 100,000 in the 1890s to fewer than 5,000 by 1906. Along with disenfranchisement came Jim Crow segregation and exclusion from equal access to public services like education, public transportation, and the justice system.

Emancipation Day Celebration band, June 19, 1900. Photo from Grace Murray Stephenson. Public domain from the University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, ...MORE

Texas freedpeople kept alive the memory of emancipation and Reconstruction in ceremonies that eventually became named Juneteenth. Begun in 1866, the year after the proclamation, and growing dramatically after an 1867 parade in Austin, Juneteenth festivals spread to towns and churches across Texas. At Houston’s aptly named Emancipation Park, freedpeople flew flags, sang patriotic songs, paraded in uniform, and defended the memory of Reconstruction. As African-Americans moved north and west, Juneteenth moved with them to hundreds of towns and cities. With other, often regionally based, holidays like Watch Night, Eighth of August, Memorial Day, and Fourth of July, Juneteenth became a way for African-Americans to celebrate their gains, sustain their hopes, assess their defeats, and plan paths forward.

Their efforts should be models for our own, fledgling struggle to remember the gains and promise of Reconstruction. Despite wide-ranging efforts to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Civil War battles, there have been thus far only scattered efforts to mark the approaching anniversaries of Reconstruction.

In part this is because Americans remain confused about the period after the Civil War’s battles ended. Although historians—none more so than Columbia University’s Eric Foner—have shown the extraordinary political, economic, and legal gains of Reconstruction, many Americans either cling to outdated stories of corruption or have virtually no sense at all of what happened once the battles ended. A false story of Reconstruction spread by propagandists for Jim Crow segregation and disseminated in popular culture through Birth of a Nation continues to shape the national imagination.

But this Juneteenth, there is reason to hope that’s changing. Recognizing the importance of the 13th, 14th, and 15th constitutional amendments passed during this era, the U.S. Senate last week termed the period the nation’s “Second Founding,” though without using the word Reconstruction. Recently, the National Park Service commissioned a National Historic Landmark Theme Study on Reconstruction to identify landmarks that capture the dramatic story of the era.

Now, as we approach the 150th anniversary of the events that ended slavery and constructed meaningful rights for all Americans, we should look to Juneteenth as a model for commemorating Reconstruction. By grappling publicly—in parks and in programs—with the accomplishments of ending slavery and constructing equal rights, as well as the overthrow of Reconstruction and equal rights in Jim Crow, we can begin to wrestle with the impact that events like Juneteenth had upon the nation we live in. While the stories that begin with Granger’s proclamation on Galveston Island 150 years ago today may not conclude as neatly as the battlefield stories of the Civil War, they are just as crucial to the story of the nation we are today.

For more information, see:

- Sowandé Mustakeem, “Juneteenth,” in Junius P. Rodriguez, ed., Encylopedia of Emancipation and Aboliiton in the Transatlantic World

- Randolph B. Campbell, Grass Roots Reconstruction in Texas, 1865-1880

- Carl H. Moneyhon, Texas after the Civil War: The Struggle of Reconstruction

- William L. Richter, The Army in Texas during Reconstruction, 1865-1870

- James Smallwood, Barry A. Crouch, and Larry Peacock, Murder and Mayhem: The War of Reconstruction in Texas

- Elizabeth Hayes Turner, “Juneteenth: Emancipation and Memory,” in Gregg Cantrell and Turner, eds., Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas

Gregory P. Downs is a professor of history at the University of California, Davis, and author of After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War and The Second American Revolution: The Civil War-Era Struggle over Cuba and the Rebirth of the American Republic.

Get the latest about voting rights and more in the TPM newsletters.

Spread the word