It is Saturday afternoon and the Christmas market in Hénin-Beaumont is deserted. A light rain is falling on the town, adding a layer of sadness to the place.

In front of the town hall, on Place Jean-Jaurès, the PCF (French Communist Party) office has closed its shutters. A small notice pasted to the door urges voters not to succumb to the siren call of the extreme right.

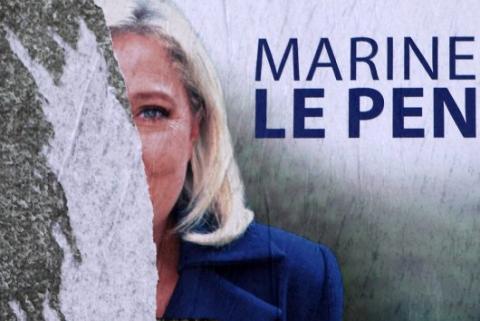

It is the eve of the second round of regional elections. The next day will see the Front National of Marine Le Pen garner a million votes in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais Picardie region – that’s almost 43 per cent of the ballot. Still, it is not enough to win this region where the far right party’s popularity has been rising steadily since 2002.

But in Hénin-Beaumont, the party leader’s fiefdom, it is by no means considered a defeat. “Little by little, we are gaining ground,” a local FN supporter tells Equal Times. “It’s inevitable! Even though the left and the right are united against us, the vote for the FN is growing with every election. So even if we don’t win tomorrow, for us, it will still be a victory!”

A few kilometres from Lens, a mining basin hit head on by the economic crisis, the discourse of the Front National is hugely popular. Once a bastion of the communist party, the small town of Hénin-Beaumont fell to the Front National in March 2014, along with a dozen or so other French municipalities during the last local elections.

The mayor, Steeve Briois, is a ‘son of the soil’. This long-time activist with a working-class background has strongly contributed to turning his town into the FN’s laboratory in the region, a bridgehead for the conquest of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, with its disenchanted population and a political class struggling to provide it with answers.

“The unemployment rate in our region is four points higher than the national average,” explains Pascal Catto, general secretary of the CFDT (Confédération Française Démocratique du Travail) for the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region. “It’s a really serious problem here, to the extent that, in some places, unemployment spans several generations. The Front National capitalises on that public.”

Unemployment, poverty and instability are amongst the many ills fuelling the resentment, the fear and the sense of insecurity. “People have lost all hope. So they turn to the Front National, which promises them the earth and lures them in with the prospect of a solution their problems.”

A sizeable challenge for trade unions

For the trade union movement, combatting the FN has become a real challenge in the region. Whilst in the past FN voters would keep a low profile, they now express their views without reserve and are rallying support in their workplaces, in each and every sector.

Worried about their jobs or their retirement, many workers in Nord-Pas-de-Calais are seduced by the rhetoric of Marine Le Pen. “When you hear them talk, you almost feel like giving them a CGT card!” exclaims Christelle Domain, departmental training and education secretary for the CGT (Confédération Générale du Travail).

“The concerns of Front National voters are, in fact, much the same as ours, but the solutions the far right proposes could not be further from the values of trade unionism. The challenge for us is to deconstruct the discourse of the FN, and to convince workers that the solutions this party is proposing to improve their everyday lives are fabrications.”

The CGT is, moreover, about to launch training for its workplace representatives to help them to counter the arguments of the extreme right as part of their trade union work within companies.

“It’s easier to blame refugees than to call into question the role of capital in the economic crisis,” explains Domain, by way of example. “It’s up to us to explain that to workers. It’s up to us to organise the mobilisation.”

But how can an alternative be offered when social exclusion continues to rise, despite decades of voting for the left? What can be done to persuade people that the Front National is not a solution, when traditional parties have failed to lift this region out of poverty?

“The left-wing governments have done their job,” says Catto. “But they have not acted responsibly when it comes to telling people about the reasons for the crisis. There is a lot of work to be done in terms of educating the general public. Policies also need to be implemented to foster the reestablishment of social ties.”

One of the challenges for the trade union movement is to dare to talk about the crisis, about globalisation and about Europe.

For Catto, it is essential that unions stop blaming Europe for everything, as does the Front National, as whilst some EU policy decisions do warrant criticism, it should not be forgotten that the region benefits from financing from the European Regional Development Fund. In Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Europe costs each household €300, on average. But they receive €600 in return. That is something the extreme right never tells people.”

Countering the far right’s arguments at the grassroots is a sizeable challenge, and there is no certainty the trade unions will be able tackle the job alone.

“Politicians need to restore people’s hope. Because in 2017 [for the presidential elections], I’m not sure we’ll be able to bar the way as we have done this time,” concludes Domain.

Grégoire Comhaire is a journalist specialised in the Middle East and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He has been a regular visitor to the region for several years and works with various media outlets in Belgium and Canada.

This article has been translated from French.

Spread the word