Slaves freed themselves. With this majestic assertion in 1935, W.E.B. Du Bois all but cemented Black Reconstruction as one of the most influential American history books of the twentieth century. At the time of its publication, it was widely denounced. Writing from the depths of the Great Depression, and amidst a burgeoning black communist internationalism, Black Reconstruction was Du Bois at his finest. By deftly applying classical Marxist analysis to a population so often overlooked by its orthodoxies, Du Bois’s general strike thesis emerged not only as a historical corrective, but as a stark critique of Western philosophy and modern academic inquiry itself. It brought together the study of class with the study of race and foreshadowed what we now call intersectionality. Yet, it also sat on the shelf for decades until, like so many great masterpieces, it was dusted off well after its creator’s death and celebrated only in Du Bois’s absence. As the great American poet/sometimes performance artist Kanye West reminds us: “people never get the flowers when they can still smell them.”

Du Bois’s insistence on black people as a revolutionary proletariat during the Civil War pointed to a glaring hole in both Marxist theories surrounding slavery and the more general study of African Americans by professional academics. Yet even as he bemoaned the neglect of black people within the intellectual annals of modernity, Du Bois paradoxically worked outward from a deep grounding in German Romanticism, classic liberalism, and traditional political theory. As a seminal figure in what Columbia University Professor Robert Gooding-Williams has since branded “Afro-Modern Political Thought,” Du Bois’s general strike thesis continues to cast a long shadow over contemporary historiography and black intellectuals alike. It also represents a place where Du Bois’s often-bemoaned elitism seems to fizzle away into oblivion. Eighty years later lessons still abound in Black Reconstruction. This is true not only for scholars working on postemancipation America, but for today’s diverse cohort of intellectual historians who are constantly at risk of ignoring the next Du Bois in their midst.

THE GENERAL STRIKE

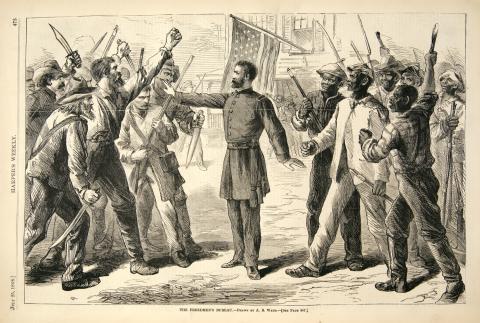

The elegance (and some would say folly) of Du Bois’s general strike thesis rests upon its simplicity. Slaves are workers. As workers, slaves constantly struggled with their masters not only over their working conditions but over their legal and social status as well. The end game for any slave insurgency was not just to own the means of production but to own one’s very self. This yearning for freedom found its climax during the American Civil War where slaves increasingly ran away, took up arms against their masters, and intentionally sabotaged and disrupted global cotton production. These actions were not accidents. They were a form of politics. They emanated from a class conscious slave community. For Du Bois, the general strike forced the hand of President Lincoln while turning a war to save the Union into a war to end slavery. In this way, the American Civil War should not be euphemistically romanticized as a ‘war between the states’ but instead re-understood as the most massive slave revolt in the history of the New World. Slaves freed themselves. It was a revolution—one that came and went. “A splendid failure.”

While many scholars have subsequently taken issue with Du Bois’s lack of nuance and his excessive commitment to a Marxist teleology, the long line of contemporary historians who have built upon the general strike thesis (to one degree or another) is by now a who’s who of the most celebrated Americanists working today. Yet, in 1935, Du Bois found few friends outside of a small circle of black activists, white political dissidents and intellectual radicals. In the field of Reconstruction, he was almost single-handedly facing a brick wall of white supremacist scholarship that had taken hold in nearly every elite history department in America. Yet Du Bois courageously named names and called out the profession for what it was. William A. Dunning, John W. Burgess, and a host of other celebrated scholars working on Reconstruction were lambasted by Du Bois for perpetuating “The Propaganda of History.” The now infamous Dunning School held that slaves were docile, unprepared for freedom, and racially inferior. The mythology of the Lost Cause was in full effect from Columbia to Johns Hopkins University. The North and the South had apparently fought gallantly over just about anything and everything but slavery—emerging in the end as a divinely unified and thoroughly perfected nation. Du Bois fought back.

Even as he was clearly swimming upstream against a pro-capitalist, white-supremacist dominated historical profession, Du Bois’s focus on class conflict, rebellion, and materiality did put him in league with a small but influential group historians in the Progressive School including Mary and Charles Beard, Arthur Schlesinger, Sr., and a young C. Vann Woodward. He also found refuge with an even smaller group of Marxist historians, including one of the first to take his general strike thesis seriously, Herbert Aptheker. Du Bois, however, was not as singularly unique as historians today imagine him. Black Reconstruction clearly built upon (and even borrowed a few opening chapter titles) from the first black Marxist interpretation of Reconstruction, Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South published by his mentor and former boss T. Thomas Fortune in 1884. In many ways, Du Bois’s general strike thesis re-stated what Fortune had expressed as a future aspiration (a general strike by a united interracial proletariat) and transformed it into the tangible reality of the Civil War past. It wasn’t until the 1960’s, however, with the rise of the revisionists and, more importantly, the postrevisionists, that the general strike thesis started by Fortune and perfected by Du Bois finally took hold.

ENTER THE MASSES

Vincent Harding’s 1981 There is a River undeniably stands out as one of the earliest touchstones for the general strike thesis’s (post)modern revival. Eric Foner’s landmark 1988 synthesis, Reconstruction, also explicitly endorsed many aspects of Black Reconstruction including the centrality of slaves and slavery to the Civil War and its aftermath. Regarding the general strike thesis, however, Foner, like Eugene Genovesebefore him, was apprehensive about the extent to which slaves actually freed themselves amidst so many other causal contributors. Genovese was critical of slaves for not being more daring in their rebellion and Foner, for his part, was desperately trying to redeem the Radical Republicans and white abolitionists as central actors in Emancipation. Both, however, were already working in the face of a vast scholarly tidal wave. The publication of Slaves No More in 1992 was the culmination of over a decade of research by several dozen scholars including Ira Berlin, Thavolia Glymph, and Barbara Fields who unearthed a small mountain of evidence at the Library of Congress which demonstrated emphatically that slaves were in fact “the prime movers in securing their own liberty.” This vindication was followed shortly by Julie Saville’s The Work of Reconstruction in 1994 which provided a thick description on the ground of a black proletariat struggling to emancipate themselves before, during, and after the American Civil War. While a brief and half-hearted push-back came in 1995 from none other than James McPherson (who fully acknowledged that slaves played an important, but perhaps not the pivotal, role in their own emancipation), most historians fell in line with the new consensus. Steven Hahn’s 2003 A Nation Under Our Feet went even deeper into slave politics and the kinds of grass-root organizing that enabled slaves to both topple slavery and continue the struggle for freedom after emancipation. Stephanie McCurry’s 2010 Confederate Reckoning further demonstrated how slaves, along with poor white men and women, fought internally against the anti-democratic Confederate state thereby producing the ungovernable Confederate nation that lead to slavery’s spectacular collapse. Chandra Manning took the opposite track in her 2007 book What This Cruel War Was Over and showed how slaves carefully acted during the Civil War to commandeer white Union soldiers into transmitters of their abolitionist views to a Northern public whose shift in opinion about the war’s meaning ultimately enabled the end of slavery. James Oakes has pointed out that Northern policy and Emancipation law presupposed and depended upon slave rebellion as a central part of the legal framework and practical process of emancipation. Most recently, the general strike thesis has received its own synthesis with 2014’s I Freed Myself by David Williams who proceeds to pound the table even harder for the widespread adoption of Du Bois’s key insight. In short, recent scholarship, over time, has done less to question the general strike thesis and more to show in increasingly sophisticated ways exactly how it came to be. Du Bois won.

While the history of the general strike thesis may seem to point to a happy ending, its road to that end does not. We must always remember that Du Bois was dismissed, harassed, policed, and ignored for a truly unforgivable amount of time. What radical ideas are we ignoring today that will appear as common sense to the academy eighty years from now? Put another way, what is the general strike thesis of the twenty first century? Meat is murder? The earth is dying? Reparations are due? Capitalism is slavery? Perhaps by definition, our collective imaginations cannot picture exactly what the next unheralded general strike thesis will be. What Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction shows us, however, is that someone is probably thinking about it right now.

This essay is part of an upcoming roundtable at The Society of U.S. Intellectual Historycommemorating the 80th Anniversary of W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction. The series is being edited by Robert Green II and will be appear here.

Spread the word