Eight years ago this month, I published in these pages an open letter to the next president titled, “Farmer in Chief.” “It may surprise you to learn,” it began, “that among the issues that will occupy much of your time in the coming years is one you barely mentioned during the campaign: food.” Several of the big topics that Barack Obama and John McCain were campaigning on — including health care costs, climate change, energy independence and security threats at home and abroad — could not be successfully addressed without also addressing a broken food system.

A food system organized around subsidized monocultures of corn and soy, I explained, guzzled tremendous amounts of fossil fuel (for everything from the chemical fertilizer and pesticide those fields depended on to the fuel needed to ship food around the world) and in the process emitted tremendous amounts of greenhouse gas — as much as a third of all emissions, by some estimates. At the same time, the types of food that can be made from all that subsidized corn and soy — feedlot meat and processed foods of all kinds — bear a large measure of responsibility for the steep rise in health care costs: A substantial portion of what we spend on health care in this country goes to treat chronic diseases linked to diet. Furthermore, the scale and centralization of a food system in which one factory washes 25 million servings of salad or grinds 20 million hamburger patties each week is uniquely vulnerable to food-safety threats, whether from negligence or terrorists. I went on to outline a handful of proposals aimed at reforming the food system so that it might contribute to the health of the public and the environment rather than undermine it.

A few days after the letter was published, Obama the candidate gave an interview to Joe Klein for Time magazine in which he concisely summarized my 8,000-word article:

“I was just reading an article in The New York Times by Michael Pollan about food and the fact that our entire agricultural system is built on cheap oil. As a consequence, our agriculture sector actually is contributing more greenhouse gases than our transportation sector. And in the meantime, it’s creating monocultures that are vulnerable to national security threats, are now vulnerable to sky-high food prices or crashes in food prices, huge swings in commodity prices, and are partly responsible for the explosion in our health care costs because they’re contributing to Type 2 diabetes, stroke and heart disease, obesity.”

Was it possible that the food movement — the loose-knit coalition of environmental, public-health, animal-welfare and social-justice advocates seeking reform of the food system — might soon have a friend in the White House?

This, after all, was not the only sign that Barack Obama recognized the need to reform industrial agriculture and stand up to Big Food. In his long-shot quest to win the Iowa caucuses, he courted the state’s small farmers, many of whom feel victimized by the oligopolies that dictate the prices and terms by which they’re forced to sell their crops and livestock. He also courted rural Iowans whose communities are increasingly befouled by the hog and chicken CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations) replacing the state’s family farms. Though CAFOs pollute the air and water like factories, they are regulated like farms, which is to say very lightly, when at all. Obama promised to change all that, vowing on the campaign trail to bring CAFOs under the authority of the federal Clean Air and Clean Water Acts and Superfund program “just as any other polluter.” He also promised to give communities “meaningful local choice about the placement, expansion and regulations of CAFOs.” To big pork and chicken producers, which had largely succeeded in gutting both local and federal authority over CAFOs, these were fighting words. And agricultural reformers cheered.

They also cheered when, at a 2007 agricultural meeting in Iowa, Obama declared that Americans had a right to know where in the world their food came from and whether it had been genetically modified. In ways small and large, Obama left the distinct impression during the campaign that he grasped the food movement’s critique of the food system and shared its aspirations for reforming it.

But aspirations are cheap — and naïveté can be expensive. A few days after the candidate’s interview with Time, Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa, a.k.a. the Senior Senator from Corn, blasted Obama for his heretical views on American agriculture, suggesting he was blaming farmers for obesity and pollution. A campaign spokesman quickly walked back Obama’s remarks, explaining that the candidate was merely “paraphrasing an article he’d read.” Big Food had spoken, and the candidate — an urban politician from Chicago — got the first of what would turn out to be many unpleasant tutorials on the industry’s sway in Washington.

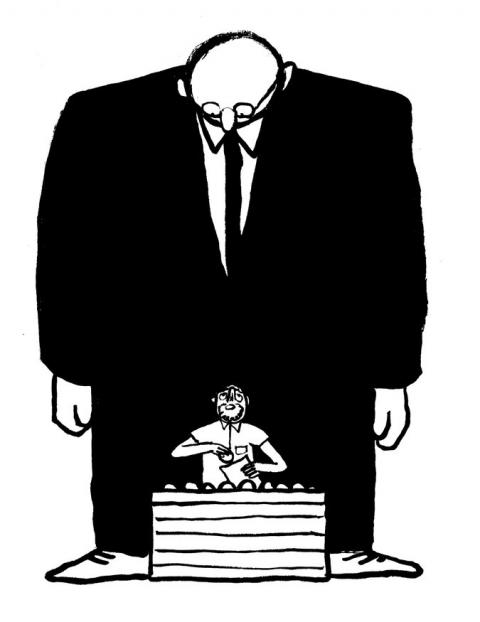

In order to follow the eight-year drama starring Big Food and both Obamas — for soon after the inauguration, the first lady would step in to play a leading role — it’s important to know what Big Food is. Simply put, it is the $1.5 trillion industry that grows, rears, slaughters, processes, imports, packages and retails most of the food Americans eat. Actually, there are at least four distinct levels to this towering food pyramid. At its base stands Big Ag, which consists primarily of the corn-and-soybean-industrial complex in the Farm Belt, as well as the growers of the other so-called commodity crops and the small handful of companies that supply these farmers with seeds and chemicals. Big Ag in turn supplies the feed grain for Big Meat — all the animals funneled into the tiny number of companies that ultimately process most of the meat we eat — and the raw ingredients for the packaged-food sector, which transforms those commodity crops into the building blocks of processed food: the corn into high-fructose corn syrup and all the other chemical novelties on the processed-food ingredient label, and the soy into the oil in which much of fast food is fried. At the top of the Big Food pyramid sit the supermarket retailers and fast-food franchises.

Each of these sectors is dominated by a remarkably small number of gigantic firms. According to one traditional yardstick, an industry is deemed excessively concentrated when the top four companies in it control more than 40 percent of the market. In the case of food and agriculture, that percentage is exceeded in beef slaughter (82 percent of steers and heifers), chicken processing (53 percent), corn and soy processing (roughly 85 percent), pesticides (62 percent) and seeds (58 percent). Bayer’s planned acquisition of Monsanto promises to increase concentration in both the seed and agrochemical markets.

Each industry sector is represented in Washington by one or more powerful lobbying organizations. The Grocery Manufacturers Association (G.M.A.) represents the household brand names, like General Mills, Campbell’s, PepsiCo, Nestlé, that make and market the packaged foods and beverages in the supermarket. The North American Meat Institute represents Big Meat, working alongside each animal’s dedicated trade association (the National Pork Producers Council, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association and the National Chicken Council). The American Farm Bureau Federation ostensibly speaks for the growers of the commodity crops. The National Restaurant Association is the voice of the fast-food chains. The euphemistically named CropLife America speaks for the pesticide industry.

These groups each have their own parochial furrows to plow in Washington, but they frequently operate as one — on such issues as crop subsidies, which benefit all, or the labeling of genetically modified food, which disadvantages all. In recent years the various sectors have been driven closer by the emergence of a common adversary: a food movement bent on checking their dominance in the marketplace and their freedom to operate with a minimum of oversight. So while it is something of a simplification, it does make sense to talk about Big Food as a single entity — and an impressively powerful one at that.

Soon after the inauguration, the Obamas gave Big Food a case of heartburn when, in the spring of 2009, Michelle Obama planted an organic vegetable garden on the White House lawn, a symbolic but nevertheless powerful act that thrilled the food movement. (Alice Waters had first proposed the idea of a White House victory garden to the Clintons, and the idea was picked up in 2008 in an online petition, as well as in my “Farmer in Chief” letter.) The first lady also helped establish a farmers’ market a block from the White House; a photo op featured her heaping a market basket with local produce and singing the praises of fresh vegetables.

Big Food had a big problem with the first lady’s food talk, and especially with one modifier: organic. In fact, she seldom if ever used that word to describe her garden, but the White House news release announcing the garden made much of the organic practices they were using — fertilizing with compost, using beneficial insects instead of chemicals to control pests and so on — so the press invariably referred to it as the White House’s “organic garden.”

CreditIllustration by Jean Jullien

A spokesman for the American Council on Science and Health, a chemical-industry front group, called the Obamas “organic limousine liberals,” warning that organic farming would lead to famine and calling on the first lady to use pesticides in her garden — evidently whether she needed them or not. The Mid-America CropLife Association wrote a letter to the president suggesting that, by planting an organic garden, his wife had unfairly impugned conventional agriculture. A minor skirmish, perhaps, but also a shot across the bow.

That summer, the new administration mounted what would turn out to be its most serious challenge to the food industry. In fulfillment of Obama’s pledge to America’s small farmers and ranchers, the administration began an ambitious antitrust initiative against Big Food, investigating the market power and anticompetitive practices of the poultry, dairy, cattle and seed industries. Attorney General Eric Holder and the chief of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, Christine Varney, joined with Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack in an unprecedented listening tour through rural America, holding a series of public hearings on concentration in the food industry over the course of 2010.

At considerable risk to their livelihoods, ranchers and farmers testified to the abuses they suffered at the hands of the small number of companies to which they were forced to sell, often on unfavorable terms. In many regions, the officials heard, there were so few buyers for cattle that the big four meatpackers were able to dictate prices, impose unfair contracts and simply refuse to buy from ranchers who spoke out. Chicken farmers testified about how they had been reduced to sharecroppers by the industry’s contract system. Companies like Tyson and Perdue make farmers sign contracts under which the companies supply the chicks and feed and then decide how much to pay for the finished chickens based on secret formulas; farmers who object or who refuse any processor demands (to upgrade facilities, for example) no longer receive chicks, effectively putting them out of business. Holder, Varney and Vilsack expressed sympathy, voiced concern, vowed action and promised the farmers who came forward that they would suffer no retaliation for their testimony. Varney even offered to give one skittish chicken farmer her phone number at Justice.

The Agriculture Department already had the authority to curb many of these abuses under the Packers and Stockyard Act of 1921, which established a powerful antitrust unit in the department now called the Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyard Administration, or Gipsa. But Gipsa was effectively shuttered during the George W. Bush administration; dozens of farmer complaints against the meatpackers were found stuffed in a drawer, according to an article in Washington Monthly by Lina Khan. In response to pressure from farmers to do something about anticompetitive practices in the meat industry, the 2008 farm bill — the gigantic piece of legislation that roughly every five years establishes the rules of the farming game in America — included a measure instructing the U.S.D.A. to issue new Gipsa rules and enforce them. In June 2010, Vilsack announced a set of regulations to “make sure the playing field is level for producers.” Specifically, the proposed rules made it easier for producers to sue packers for unfair or deceptive practices and protected them from retaliation.

Big Meat, in particular, was not happy. It opened its wallet, spending roughly $9 million on lobbying in 2010, not including political contributions to members of the agriculture committees in Congress. One of those committees called Edward Avalos, a U.S.D.A. undersecretary, to Capitol Hill to defend the new rules in a hearing at which the poor fellow was grilled mercilessly for doing his job. (The story is well told in Christopher Leonard’s recent book, “The Meat Racket.”) Vilsack apparently got the message; he consented to postpone the new regulations. This gave the industry time to mount a “grass roots” lobbying campaign against the Gipsa rules, in which contract chicken farmers were recruited by the National Chicken Council to send Congress letters drafted by lobbyists. Vilsack, in retreat, offered to scale back the new rules to make them more palatable. But the industry would accept nothing less than complete victory: It succeeded in killing any new curbs on its market power when the House Appropriations Committee stripped funding for Gipsa enforcement from the U.S.D.A.’s spending bill for 2012. And 2013, and 2014, and 2015.

But what about the listening tour and the public hearings? Even though the hearings had established a pattern of anticompetitive behavior, the entire antitrust effort was quietly and ignominiously dropped. No more was ever heard of it. The farmers who testified were left to fend for themselves in the marketplace. (As for dialing up Christine Varney? Forget it: She returned to private practice in 2011, seven months after the last public hearing.) Obama had launched the most serious government challenge to the power of Big Food since Teddy Roosevelt went after the Meat Trust a century ago, but in the face of opposition it simply evaporated.

A case can be made that Michelle Obama, with little more at her command than the power of persuasion and her personal example, has achieved more on food issues than the rest of the administration. (It helped that she chose to focus on issues that resonated with ordinary Americans concerned about their children and did it in a voice that never sounded elitist.) Among her most meaningful accomplishments: the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, which she made a priority and which raised nutritional standards for the meals served in the Federal school lunch program and eliminated the sale of junk food elsewhere in the public schools. At her urging, food companies have taken steps to make their products less unhealthful. Federal nutrition guidelines have been made clearer and more sensible. And her Let’s Move campaign has raised the public’s consciousness about the importance of food to our health and well-being, which has laid the groundwork for more far-reaching reform in the future.

In March 2010, Michelle Obama gave a speech to the G.M.A. that surprised many of the executives in the room with its sophistication and toughness. She issued a stern challenge to Big Food, doing it in such a way as to make clear she wasn’t about to fall for the industry’s usual bag of P.R. “health” tricks. “We need you not just to tweak around the edges,” she said, “but to entirely rethink the products that you’re offering, the information that you provide about these products and how you market those products to our children.” She continued: “What it doesn’t mean is taking out one problematic ingredient only to replace it with another. While decreasing fat is certainly a good thing, replacing it with sugar and salt isn’t. And it doesn’t mean compensating for high amounts of problematic ingredients with small amounts of beneficial ones — for example, adding a little bit of vitamin C to a product with lots of sugar, or a gram of fiber to a product with tons of fat doesn’t suddenly make those products good for our kids. This isn’t about finding creative ways to market products as healthy. As you know, it’s about producing products that actually are healthy.”

The speech got the industry’s attention. Sean McBride, a food-industry consultant who at the time worked for the Grocery Manufacturers Association, told Politico about the Obamas’ concern with the food system that “you had a number of companies who were scared to death.” But according to Scott Faber, then the chief lobbyist for G.M.A., several members of his group recognized an important opportunity when Michelle Obama came calling on the industry to “step up its game.” The obesity epidemic “had put a bull’s-eye on the food industry’s back,” Faber explained. Here was a chance to remove it, with the first lady’s help.

In response, the industry adopted a clever two-track strategy to deal with the challenge laid down by the first lady. On a very public track, industry leaders engaged the foundation that she formed, the Partnership for a Healthier America, in negotiating a series of private-sector partnerships — a series of voluntary efforts that the industry hoped would help avert new regulations — a possibility that Obama raised in her speech. Supermarket retailers pledged to promote more healthful foods in their stores, like fresh produce. A group of 16 leading food makers pledged to reduce the total number of calories in the food supply by a whopping 1.5 trillion. Food makers pledged to reduce harmful ingredients in processed food, like salt and sugar, while boosting healthy ingredients, like whole grains. In exchange for entering into these agreements, several industry partners were granted invaluable photo ops with the first lady. In the case of Subway and Walmart, she made appearances in their stores.

Michelle Obama has celebrated these partnerships as significant achievements, but do they match the ambitions of her 2010 speech, with its call for industry to do more than “tweak around the edges” and instead to “entirely rethink the products you’re offering”? Removing unhealthful ingredients from processed foods is undeniably a good thing. Yet making junk food incrementally less junky is a dubious achievement at best. It tends to obscure the more important distinction between processed food of any kind and whole foods. What began as a cultural conversation about gardens and farmers’ markets and real food became a conversation about improved packaged foods, a shift in emphasis that surely served the interests of Big Food. While it can be argued that this was simply a concession to reality — because most Americans eat processed foods most of the time — to give up on real food so fast was to give up a lot.

As for Big Food’s ballyhooed 2010 agreement with the first lady to remove 1.5 trillion calories from the American food supply by 2015, well, what does this even mean? Precious little, it turns out. The Healthy Weight Commitment partnership agreement stipulated an independent evaluation of the results, sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and recently completed. It concluded that total calories in the food supply were already declining by more than a trillion a year — soda sales, for example, have been plunging — and the evaluators determined that market trends would have guaranteed greater declines even in the absence of any pledge by the industry. The dean of the School of Nutrition at Tufts characterized the whole initiative as “an easily publicized but deceptive ‘sham’ pledge” and “an apparent industry charade” — at the public’s and the first lady’s expense.

Even as Big Food sought to publicly partner with the first lady in her war on obesity, it engaged in a much less visible campaign to forestall any new law or tax or regulation threatening its freedom to make and market junk food. Big Food’s biggest victory on an issue Michelle Obama cared about was its success in derailing voluntary guidelines for marketing food to kids. The proposed guidelines, which were developed by an interagency task force consisting of the Federal Trade Commission, the U.S.D.A., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the F.D.A., set standards for salt, sugar and fat in processed foods that, if exceeded, could not be marketed to kids — at least by companies that agreed to participate in the program. The draft set of guidelines, released in April 2011, were written in such a way that several classic kids’ foods like sweetened yogurt (which can have more sugar per ounce than Coca-Cola), canned soups (many of which are sodium bombs) and even Cheerios (also full of salt) would not pass muster as currently formulated. Though the recommendations did not have the force of law, they were nevertheless anathema to industry. “The guidelines were a turning point for us,” Scott Faber told me. The G.M.A. was now prepared to directly take on the administration — and the first lady.

At the time, the White House, spooked by the Tea Party election of 2010 (which cost the Democrats control of the House) and by charges from Republicans and business leaders that the president was unfriendly to business, had begun an effort to repair relations with corporate America. In January 2011, Bill Daley, the former commerce secretary and investment banker, was installed as a business-friendly chief of staff. That spring, the G.M.A. waged an aggressive lobbying campaign to water down the marketing guidelines, aimed at both Congress and the White House. In the months that followed, the G.M.A., along with leaders of food and media companies, was granted a meeting with Valerie Jarrett, a senior adviser to the president, in the White House to discuss the issue. Public-health advocates and congressional supporters of the guidelines were surprised that neither the first lady nor the president spoke out in support of them. “I’m upset with the White House,” Senator Tom Harkin, chairman of the Senate Health committee, told Reuters. “They went wobbly in the knees.”

The White House had left the administration’s own interagency task force to the mercies of a Republican-controlled House, which effectively killed off the voluntary guidelines. Faber, who as the G.M.A.’s chief lobbyist helped orchestrate this rout, told me he was “frankly surprised the administration never came back with a revised set of guidelines.” Evidently the White House had lost its stomach for this particular fight.

That wasn’t the only one, either. In the years after, Big Food scored a series of victories over even the most reasonable attempts to rein in its excesses. Remember the pledge to Iowans to regulate CAFOs (“just as any other polluter”) and stanch the flood of animal waste they were loosing on rural America? For the government to regulate CAFOs at all, it must first know where they are and how many animals they house, a survey the E.P.A. has been trying to conduct since 2008. But in July 2012, after lobbying by meat producers, the E.P.A. dropped its effort just to count the nation’s CAFOs.

CreditIllustration by Jean Jullien

Big Meat also prevailed when challenged on the misuse of antibiotics in animal agriculture — a problem that Margaret Hamburg, the F.D.A. chief, likened to having your “hair on fire,” since it is leading to antibiotic resistance and compromising the drugs we depend on. But when the F.D.A. finally acted in 2013, it came forth not with regulations but with a voluntary program, one that has so far failed to reduce the use of antibiotics in the meat industry. The food industry even managed to undermine the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, Michelle Obama’s signature legislation, which the Republican Congress is refusing to reauthorize.

But perhaps we will look back on Big Food’s single most important victory during the Obama years as one it didn’t even have to break a sweat achieving, since it involved an issue on which it wasn’t even challenged. The administration undertook an ambitious campaign to tackle climate change by stringently regulating industries responsible for greenhouse gases, notably energy and transportation. For whatever reason, though, the administration chose not to confront one of the largest emitters of all: agriculture.

Yet the future of food will be decided not only in the corridors of power, but in the wider culture as well, and here Big Food has a big and growing problem — one that some of its political victories have only exacerbated. For example, the industry’s $100 million fight to stop G.M.O. labeling has pitted many food companies against the overwhelming majority of their consumers, who tell pollsters they want their food labeled. This is a most uncomfortable position for consumer-goods businesses to find themselves in, which is why many of the G.M.A. member companies sought (unsuccessfully) to hide their involvement in the fight. Battling against transparency is bound to sow seeds of distrust, potentially undermining the most precious pieces of cultural capital Big Food owns: its brands.

These battles have exposed weaknesses in the facade of Big Food’s power, soft spots that some grass-roots food activists have recently figured out how to exploit. One example: Since the 1990s, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers has been organizing the tomato pickers of South Florida, some of the most underpaid and ill-treated workers in the country. In their decades-long quest to improve pay (by 1 cent per pound) and working conditions (until recently some Florida tomato pickers were effectively enslaved by their employers), the coalition tried every strategy in the book: labor strikes, hunger strikes, marches across the state. But the growers would not budge.

“Then we found the unlocked door in the castle wall,” Lucas Benitez, the farmworker who helped establish the coalition, told me. “It was the corporate brand.” Instead of going after the anonymous growers and packers, who had nothing to lose by rejecting their demands, the coalition trained its sights on the Big Food brands that bought their tomatoes: McDonald’s, Burger King, Chipotle, Subway, Walmart. In 2011 the coalition drafted a Fair Food Agreement guaranteeing a raise of a penny per pound and spelling out strict new standards governing working conditions. They then pushed the big brands to sign it, using the threat of boycotts, marches on fast-food outlets, even the public shaming of top executives and their bankers. One by the one, the Big Food brands have given in, signing the agreement and, for the first time, accepting a measure of responsibility for the welfare of farmworkers at the far end of their food chain. The coalition achieved victories that never could have been achieved in Washington.

Surely there is a lesson here for the food movement — a collection of disparate groups that seek change in food and agriculture but don’t always agree with one another on priorities. Under that big tent you will find animal rights activists who argue with sustainable farmers about meat; hunger activists who disagree with public-health advocates seeking to make soda and candy ineligible for food stamps; environmentalists who argue with sustainable cattle ranchers about climate change; and so on. To call this a movement is an act of generosity and hope. But whatever it is, it has been no match for Big Food, at least in Washington.

Whenever the Obamas seriously poked at Big Food, they were quickly outlobbied and outgunned. Why? Because the food movement still barely exists as a political force in Washington. It doesn’t yet have the organization or the troops to light up a White House or congressional switchboard when one of its issues is at stake.

“Show me a movement,” the president told Dan Barber, the New York chef and writer, who cooked a meal for the Obamas on the eve of the inauguration. The discussion had turned to the possibility of reforming the food system. Eight years later, it isn’t entirely clear that Obama has been shown that movement. You can see why the president might have concluded that it would have been foolhardy for his administration to get too far out ahead of the culture on food issues. And why he might have turned to Michelle Obama at that same meal and said, “You can talk about these issues,” as Barber recalls. “It’ll be a hell of a lot more effective than me.”

The power of the food movement is the force of its ideas and the appeal of its aspirations — to build community, to reconnect us with nature and to nourish both our health and the health of the land. By comparison, what ideas does Big Food have? One, basically: “If you leave us alone and pay no attention to how we do it, we can produce vast amounts of acceptable food incredibly cheaply.”

Big Food knows it has a serious story problem, and early in the administration it began an aggressive P.R. effort. The immediate impetus appears to have been the 2009 release of the Oscar-nominated documentary “Food, Inc.” (for which I was interviewed and served as a consultant). The film made the case that the entire food system, from the Midwestern monocultures of G.M.O. corn to the fast-food meals wrecking America’s health, was sorely in need of reform. In response to the film, and facing an administration that appeared sympathetic to such views, a coalition of agribusiness corporations, along with the Farm Bureau and various commodity groups got serious about defending the industrial food system and going after its critics. According to a September 2009 article in Agripulse, a trade publication, not only was the industry gearing up for “a pre-emptive strike against a long list of new regulations” expected from the new administration, but, just as important, it also felt the need to confront “people like Michael Pollan.”

“We’ve seen so many attacks,” Agripulse wrote. “We see Michael Pollan go on Oprah” — as I did after “Food, Inc.” came out. “What’s going to happen when those people ... start to have an impact in Washington on policies and regulations?” Thus spooked, a coalition of Big Ag companies and trade groups, including Monsanto, DuPont and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, hired Ketchum Communications, the New York P.R. firm, to organize a multimillion-dollar campaign. Ketchum promoted something called the U.S. Farmers and Ranchers Alliance, ostensibly a group of independent farmers and ranchers — though much of the funding came from agribusiness corporations — who would speak out, in public forums and on op-ed pages, to counter the writers and filmmakers who, at the time, had a big and largely uncontested microphone.

It was around this time that some of my speaking engagements at agriculture schools began falling prey to unexpected snafus and changes in plan. An invitation to speak at Washington State University in 2009, which had organized a community read of one of my books, was suddenly withdrawn, supposedly because of a budgetary crisis but according to media reports at the behest of a wheat grower on its Board of Regents. (When a prominent alumnus, a lawyer and food-industry gadfly named Bill Marler, stepped forward offering to cover my expenses, the school abruptly reversed course.) In 2010, an invitation to speak at Cal Poly, another ag school, was transformed into a debate after a donor to the school, the chairman of the biggest cattle feedlot in California, wrote to the president of the university threatening to withdraw his gift if I was allowed to speak without challenge. The University of Wisconsin, Madison, also made my book a community read and invited me to talk about it. To protest my presence, the Wisconsin Farm Bureau bused in several hundred farmers from across the state, all of them wearing the same T-shirt, printed with the legend “In Defense of Farmers.” Only the fabled niceness of Midwesterners saved me from a hail of rotten tomatoes that night.

Surely Big Food was overreacting to the threat posed by a handful of writers and filmmakers, yet the fact that they did suggests that, behind the industry’s wall of political power, there indeed lurks a vulnerability. That vulnerability is the conscience of the American eater, who in the past decade or so has taken a keen interest in the question of where our food comes from, how it is produced and the impact of our everyday food choices on the land, on the hands that feed us, on the animals we eat and, increasingly, on the climate. Though still a minority, the eaters who care about these questions have come to distrust Big Food and reject what it is selling. Looking for options better aligned with their values, they have created, purchase by purchase, a $50 billion alternative food economy, comprising organic food, local food and artisanal food. Call it Little Food. And while it is still tiny in comparison with Big Food, it is nevertheless the fastest-growing sector of the food economy.

While Big Food can continue to forestall change in Washington, that strategy simply will not succeed in the marketplace. There, Big Food is struggling to adapt to a rapidly shifting landscape it cannot control. That’s why it’s gobbling up organic and artisanal brands, hoping to learn the secret of their success — which, of course, is simply that they understand and respect the values of the new food consumer better than Big Food does. Some large food companies are voluntarily changing their practices in response to the concerns of these consumers, whether about antibiotics, animal welfare or the welfare of farmworkers. One future of food politics may lie in grass-roots campaigns targeted not at politicians in Washington but directly at Big Food and its consumers, taking aim at its Achilles’ heel: those precious brands.

For all the disappointments, the Obamas deserve credit for celebrating and nourishing Little Food. If nothing else, the spotlight of their attention helped elevate the idea of food as something worthy of public attention. As the Obamas prepare to leave the White House, Big Food can congratulate itself on retaining its political grip on Washington. It seems very unlikely that the next occupant of the White House is going to pose as stiff a challenge. Donald Trump professes to love fast food, and Hillary Clinton has longstanding ties to Big Food: Tyson was one of Bill Clinton’s first political patrons, and as a lawyer in Arkansas, Hillary Clinton served on the board at Walmart. (Though as a New York senator, she worked hard on behalf of small upstate farmers, so perhaps there is hope.) But like Goliath, Big Food can’t afford to be complacent about its size or power, not when the culture of food is shifting underfoot. Perhaps it is a sign of things to come that Scott Faber, the lobbyist who helped the industry navigate the first Obama administration, has left the G.M.A. to work for the Environmental Working Group, where he now plies his skills on behalf of the food movement’s David. Politics and policy in Washington seldom move before the larger culture does, but when that happens, it can sweep away everything in its path — Goliath included.

Michael Pollan is a contributing writer and the Knight professor of journalism at U.C. Berkeley, and the author, most recently, of “Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation.”

Spread the word