Growing up in Stone Mountain, Georgia, Kara Walker could not avoid the imagery of the Civil War. A tribute to Confederate leaders—Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson—is carved into the side of Stone Mountain itself, and every Independence Day, families gather at that side of the mountain to watch a fireworks display. Stone Mountain was also a gathering site of the second Ku Klux Klan. Those who have studied Walker’s biography know her move from California to a newly desegregated, but still very divided, Georgia in the 1980s heavily influenced her life and her art.

Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) is based on the romantic depiction of the conflict captured in the pages of Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War. In this exhibition, Walker enlarges illustrations from the original volume and stencils large black figures on top of them. The stencils are not very detailed, but those familiar with Walker’s work will be reminded of the somewhat comical and grotesque ways she shapes these figures in her silhouettes. Walker’s pieces have the same titles as the original images, which implies she’s correcting history; by adding to the original work and keeping the name the same, she tells the story of the Civil War from the slave’s perspective.

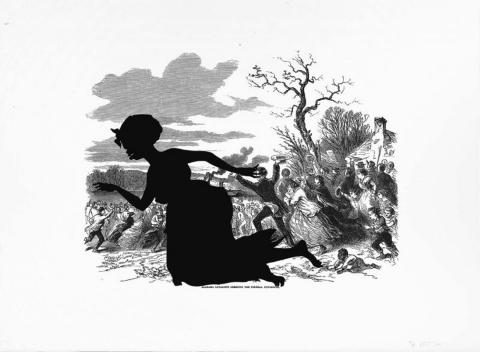

The first image of the exhibition, “Alabama Loyalists Greeting the Federal Gun-Boats,” depicts whites and African-Americans moving as a group toward gun-boats. Walker overlays a stencil of a female slave running, which kicks off the narrative that viewers follow throughout the exhibition. The scene takes place in Confederate Alabama, where some slaves might have been interested in greeting these gun-boats carrying firearms to protect the Confederacy. But the insertion of a stencil of a female runaway slave invokes the spirit of Harriet Tubman, the Underground Railroad “conductor” who guided as many as 300 enslaved people to freedom. Tubman’s presence in this exhibit is necessary, as she’s known to be the only woman to lead an armed military operation during the Civil War. The raid on the Combahee River in South Carolina resulted in the liberation of more than 750 enslaved people. With this image, Walker’s tale about slaves’ role in the Civil War begins.

Further along in the exhibition, stencils overlaid on the enlarged illustrations begin to tell a story about the fate of enslaved people during this period. Most of the illustrations that Walker chose to enlarge and use in this collection are of the places where battles were held. While the Civil War was a conflict between the Union and the Confederacy about slavery, the slaves were not exactly the forethought. Walker includes stencils of slaves with hoes, axes, and cotton bags as a means of identifying their value in this conflict. The fates of thousands of people were at stake if either side won, but there wasn’t a solid plan for what the slaves would do with their lives if they were actually freed.

The war’s outcome meant drastically different things for whites and African-Americans. While there were two armies fighting, African-Americans could be identified as a third party whose preferences weren’t considered. In “Signal Station, Summit of Maryland Heights,” there’s an image of a large pot-bellied slave with one boxing glove looking down on a smaller, more natural-looking figure with two boxing gloves. “Signal Station” recognizes the conflict between slaves about their freedom, something a lot of Civil War scholarship ignores. Freedom was a dream for some, but for others, it might have been a nightmare.

While the Confederate army fought to maintain the institution of slavery, scholars contend that it might not have been just for economic stability. Some people genuinely believed African-Americans needed to be controlled. Laws that forbade African-Americans from owning guns, for fear of an uprising, prevented slaves from joining Confederate soldiers on the battlefields until it was too late. Meanwhile, the Union enlisted fugitive slaves as spies and 200,000 African-Americans served in the Army and Navy combined.

Walker’s annotations of the Harper’s illustrations remind visitors that African-Americans also lost life and limb in the fight for their freedom. That fight, however, didn’t yield the freedom they had wished for. African Americans, to this day, endure race-based brutality from law enforcement and weapon-carrying neighbors. Though her work is intertwined with the imagery of the past, Walker’s work, at this museum at this moment in history, reflects the tensions of the present day as well.

F Street NW and 8th Street NW. Free. (202) 633-1000. americanart.si.edu.

Spread the word