Mexico’s new President, Andres Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), probably the only head of state to give two press conferences a day and then post them online, is accustomed to having his statements cause headlines. Last week it was a reporter’s question that caused a hot controversy, seemingly intended to drive a wedge between AMLO and one of his most important labor allies, the Sindicato Mexicano de Electricistas (Mexican Electrical Workers union, SME).

Reporter Rosa Elena Soto, of Acustik Noticias y La Neta Noticias, alleged corruption between Lopez Obrador's predecessor and the union, over contracts for operating the huge Necaxa hydroelectric power station. “Many of these contracts have indications that they were plagued by corruption,” she charged.

In his response, AMLO called the union “possibly the most democratic union in Mexico's history, until they viciously destroyed it in the neoliberal period.” Noting that its 44,000 members had been fired in 2009, he called for a solution to the conflict. Any corruption, he emphasized, wasn’t attributable to workers but to companies that took advantage of the situation. But López Obrador also called for consulting the discredited former leaders of the union, who had accepted government's payoffs after the firings.

This response provoked outrage from the union’s leaders. SME General Secretary Martín Esparza replied: “We walked miles and miles in demonstrations, faced with dignity those who fired the workers. We did not sell out, even as our families suffered, and we didn't just sit back with our arms folded and wait for answers. In fact, we proposed viable and novel solutions.”

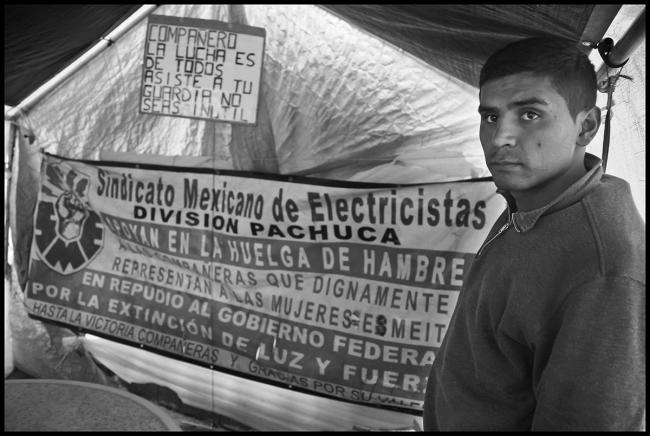

Leobardo Benítez Álvarez and other workers lived in a tent in front of the office of the Federal Electircity Commission on the Reforma in downtown Mexico City for a year to protest the firing 44,000 electrical workers and trying to smash their union. (Photo by David Bacon)

That solution is a cooperative that has taken over many of the facilities where SME members formerly worked, including the Necaxa power station in the reporter's question. This “novel solution” represents the union's hope of putting back to work the thousands of electrical workers thrown into the street a decade ago.

When López Obrador carefully noted the union's reputation, he was acknowledging the importance of its 100-year history on the Mexican left. The Mexican Electrical Workers Union, the oldest democratic union in Mexico, was founded in 1914 when the armies of Emiliano Zapata took Mexico City. Almost a century later, in 2009, the Felipe Calderón administration attempted to destroy the union and the nationalized company that employed its members. But thousands of the SME’s members refused to give up their union. Instead, they spent the next eight years “en resistencia” (in resistance).

This willingness to fight for principled labor policies is not only crucial to the country’s political left but has an impact across the border as well. Today, electrical workers in the U.S. work on an energy grid increasingly integrated with Mexico’s. To avoid the whipsawing and job competition familiar in industries like auto, U.S. unions will need Mexican partners with the kind of class-oriented unionism the SME has championed. That class-based unionism has a long history. In its new cooperative, that history is not only still alive, but has been adapted to the realities of an integrated economy dominated by pro-corporate reforms.

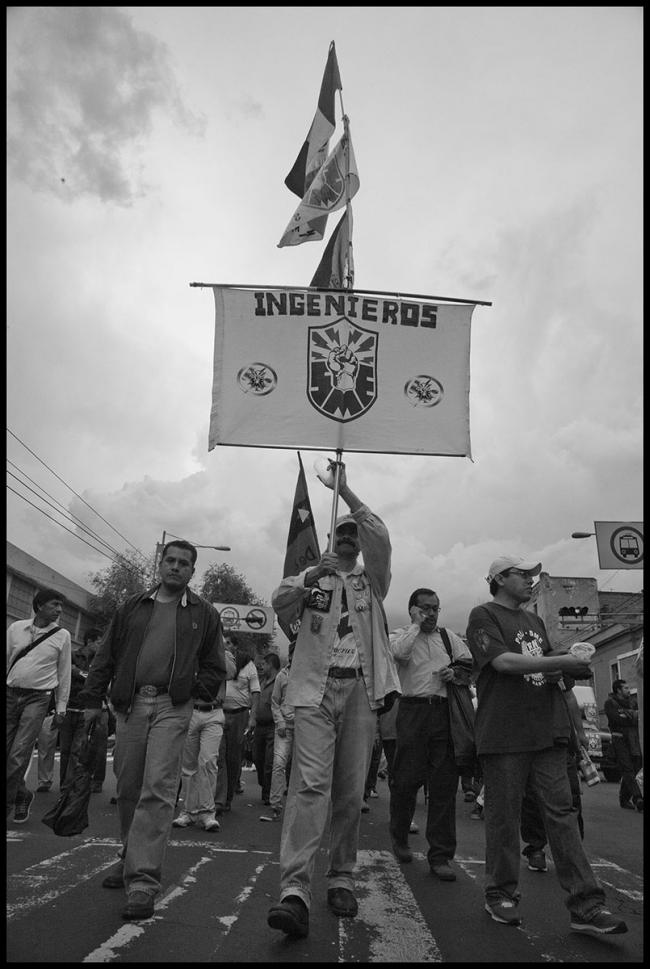

SME engineers march to protest their firing. (Photo by David Bacon)

The origins of the SME's class-based unionism

In 1898, the Compania Luz y Fuerza del Centro (the Power and Light Company of Central Mexico, LyF) was founded in Canada, and granted a concession by President Porfirio Díaz to generate, transmit, distribute, and sell electricity in central Mexico. In the middle of the Mexican Revolution, LyF workers organized the SME primarily because Mexican workers were paid much less than those working for the company from Canada and the United States.

In 1916, the SME organized Mexico’s first general strike. Union leaders were imprisoned and condemned to death, but their lives were ultimately spared after huge demonstrations. In 1936, the SME went on strike against the U.S., British, and Canadian owners of Luz y Fuerza. Mexico City went without electricity for ninety days, except for emergency medical services. The strike was successful and led to the negotiation of one of the most important labor contracts in Latin America. This contract preserved SME’s independence from the government, unlike other Mexican unions, and made it an important organization on the Mexican left.

In 1937, Amendment 27 of the Mexican Constitution made the oil and electrical industries the property of the state. Then, in 1949, the Comisión Federal de la Electricidad (Federal Electricity Commission, CFE) was established to provide power to all of Mexico—except for the area served by LyF. Nevertheless, private companies like Luz y Fuerza continued to operate under government concessions.

In 1960, the SME began to push for the nationalization of electrical power. The Mexican government subsequently purchased 90% of LyF shares, making it a state-owned and operated company. Then-President Adolfo López Mateos added a paragraph to Article 27 determining that the Mexican government has the exclusive right to provide electricity to the country.

The Sindicato Único de Trabajadores de Electricidad de la República Mexicana (Sole Union of Mexican Electricity Workers, SUTERM), headed by Rafael Galván, was established in 1972 for CFE workers. Galván, however, was expelled from the union for opposing government policy. He then organized the Tendencia Democrática del SUTERM, (Democratic Tendency of SUTERM), whose leaders were all fired. The union consequently became a pillar of support for Mexico’s governing party, the PRI. Since then, the two unions have represented the two poles in Mexican labor: an independent democratic organization with left politics, and a bureaucratized union tied to the PRI and the government.

An SME member protesting her firing. (Photo by David Bacon)

The SME contract with LyF carried strong protections, such as the guarantee of a safe workplace, vacation time, sick leave, and leaves of absence. A fund helped workers find adequate housing, and even build or buy a home. Workers also received an aguinaldo [an extra month’s salary distributed at the end of the year] and a savings fund in which the company matched workers' contributions.

“Basically, our contract meant that we had the minimum conditions for a decent life,” says SME’s External Affairs Secretary Humberto Montes de Oca. “It wasn’t some kind of privilege, but rights that cost a lot to win.” The contract set the standard for electrical workers—not just in Mexico—but throughout Latin America, Montes de Oca says. It also gave the SME the ability to mobilize workers in support of progressive politics, giving it an important presence on the left.

Fighting to Survive Neoliberal Reforms

SME’s progressive contract and politics made it a target of large corporations and their political allies, especially when the SME opposed privatization and corporate economic reform in the 1990s. In 1994, President Carlos Salinas de Gortari reversed the push towards nationalization of the electricity sector when he issued a decree allowing private companies to generate electricity and sell it to the CFE—despite the constitutional prohibition on doing so.

The first foreign electric generators, led by San Diego's Sempra Energy, began to build plants along the U.S. border in 2002. As foreign companies moved in, government managers of LyF stopped investing in the modernization of the generation and distribution systems for the publicly-owned utility. The company was forced to buy electricity at high prices from CFE and sell it at low prices to government and large- scale users. LyF's deficit ballooned, while the company's infrastructure deteriorated.

In the late ‘90s, President Ernesto Zedillo proposed an electricitya reform to open the electricity market to further private investment. He also cut the rate subsidy for the poor, asnd rates shot up 30%, notes Montes de Oca. The SME responded by forming the Frente Nacional de Resistencia a la Privatizacióon de la Industria Electrica (National Front of Resistance to the Privatization of the Electrical Industry) in 1999. In three weeks, it collected 2.3 million signatures on a petition opposing privatization., and Zedillo then abandoned his proposal.

But the next two administrations would seek to push similar reforms. In 2002, Vicente Fox proposed a similar, World Bank-backed reform. The backlash was strong: thousands of SUTERM workers marched alongside the SME in Mexico City, defying their own leadership and forcing Fox to withdraw his proposal. At that time, LyF had 5.7 million customers, serving an area with a total population of about 20 million, according to Montes de Oca.

The next administration under Felipe Calderón tried a different strategy to try to soften opposition to another privatization effort. Under Mexican labor law, the government has to certify the election of union leaders and can use this power to intervene in them. Calderón did just that by refusing to recognize the reelection of SME General Secretary Martín Esparza, provoking an internal struggle over the union’s leadership.

A week later, President Calderón declared Luz y Fuerza “non-existent” and ordered the army and police to occupy the generating plants and all other facilities. The SME was also declared “non-existent.” The government seized $80 million in union funds and tried to expel it from its union hall, where the SME's history is celebrated in a huge mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros. The union’s members defended the hall, but all 44,000 were ultimately fired. The CFE took over the operation of LyF facilities and SUTERM supplied the workers to replace the SME members.

The government offered severance pay to SME members who would renounce claims to their jobs. Facing a future with no job or income, about 28,000 accepted. The government promised jobs to former LyF workers to entice them to take the severance but never made good on its promise. More than 16,000 refused to take the payment, and declared themselves “in resistance.” With new, less experienced workers working the electrical grid, Mexico City suffered frequent service cuts and blackouts. Thirty scabs were killed by accidents on the job in the first two years afterwards.

In 2010, after staging hunger strikes in front of the CFE and the Mexican Congress, the SME declared a national strike and tried to put up strike flags on the former LyF facilities. Under Mexican law, when workers in a legal strike string the flags across the gates into the workplace, not even the owners and managers can enter, much less strikebreakers. Police, however, tear gassed and beat the strikers. Police arrested SME members and invaded activists’ homes, including that of SME General Secretary Martín Esparza.

Two years later, in 2012, the SME organized a hunger strike in El Zócalo, Mexico City’s central plaza. A Day of Indignation drew a million demonstrators. Supported by a solidarity campaign initiated by the AFL-CIO-allied Solidarity Center and the IndustriALL international labor federation, the SME negotiated a settlement with Interior Minister Francisco Blake Mora. The government agreed to reemploy the SME’s members and free 12 imprisoned leaders. Mora then died in a plane crash and the government backed out of the agreement.

The Peña Nieto administration introduced a constitutional amendment in 2013 to eliminate the exclusive right of the government to generate, transmit, distribute, and sell electricity. Once again, the SME entered negotiations for a settlement. In compensation for the $80 million in union funds the government had taken in 2009, the government agreed in 2016 that the SME could organize a cooperative, with the right to operate the former LyF generation plants and take over its former offices and other worksites.

Organizing electrical workers across borders

After NAFTA passed, electrical workers in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico began to see a future in which they would eventually be connected by a common electrical network and would face the same employers. Indeed, in 2001, Enron created 64 subsidiaries to operate within the Mexican power market, and its executives advised then-President Vicente Fox on energy policy. San Francisco-based construction giant Bechtel Enterprises partnered with Shell Generating Ltd. to set up Intergen Aztec Energy and built a plant near Mexicali, which generates 750 megawatts. Two-thirds of the power the plant generates is sold in Mexico and a third is exported to California. San Diego’s Sempra Energy Resources built another power station near Mexicali. The 600 megawatts it generates goes to the U.S. The gas for its boilers comes from the U.S. in a Sempra-built pipeline, making the plant the first true energy maquiladora.

Meanwhile, as private plant construction surged ahead, Mexico stopped almost all new construction of its own power plants. Twenty-three foreign companies were granted licenses after 2000. Even some leaders of Mexico’s ruling PRI party, including its chair Manuel Bartlett, became vocal opponents. “Look at the energy chaos in California,” he declared. “Do they want to sell the American failure to us?” After switching to MORENA, the party of López Obrador, Bartlett now heads the CFE.

Martín Esparza (Photo by David Bacon)

Below SME General Secretary Martín Esparza explains the challenges of the last years:

In reality, one purpose of Mexico's electricity reform is to permit the generation of electricity in one country (the U.S. or Mexico) in exchange for its sale and use in the other. Many multinational corporations have entered the markets. And because this year Mexico ratified the ILO Convention No. 98 about collective bargaining, unions can organize in those companies. So it’s extremely important that we have ties with unions in the U.S., to work together to organize and improve the conditions of the workers.

Yet these companies operate with no collective bargaining agreements, and avoid it by subcontractings. We want to force them to recognize unions and bargain. Our union has a national registro (legal status) that allows us to represent workers in any part of this industry, in any company. And while the transmission lines can only be operated by the Federal Electricity Commission [which has a company union, SUTERM] the government is not obligated to bargain only with it. The workers have the freedom to choose what union they want to belong to.

Right now the workers in SUTERM have a terrible contract. In the past, when the SME won important rights and benefits, all workers in the industry could ask for the same things, including workers in SUTERM. Now, because we lost our contract, workers in SUTERM are losing those benefits.

The corrupt Mexican governments of the past always support SUTERM and attacked us. We are expecting that this will change with the new administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. The new Labor Secretary, Maria Luisa Alcalde, has always supported democratic unions. We think the new government will support the freedom to organize and struggle, so we have to organize to help these workers win a good contract.

International solidarity is important for another reason also. The government is building transmission lines using direct current and new technology. Unions in the U.S. and Europe can help share the necessary skills and knowledge, to enable our members to work anywhere in the world.

The Luz y Fuerza Cooperative

Today, in the union's new Luz y Fuerza cooperative, some SME members have been able to return to work in the electrical sector. Some of them work for the cooperative itself, and others for a partnership called Fenix, between Mota Engil, a Portuguese construction company (51% of the shares) and the SME (49% of the shares). Fenix operates two generating stations, including the large Necaxa complex, and employs 49 people. Once it begins operating other stations returned by the government, the union hopes it will employ 500-600 people.

About 1,400 people currently receive some income from the cooperative. The other 15,000 people, including some who’ve already retired, are still “in resistance.” In the nine years since its members were fired, SME members have done many jobs, with some in the United States. Many returned to school and can now perform more sophisticated work, including as engineers. The union hopes they'll return to help bring the recovered plants on line, according to Montes de Oca.

Humberto Montes de Oca (Photo by David Bacon)

As Humberto Montes de Oca, SME Secretary for External Affairs, says:

We always sought a solution that would put us back to work in the electrical sector. The government even proposed training us as barbers, but we would not give up. The electrical industry has changed a lot, however, and the CFE is on the brink of bankruptcy. We can’t go back to where we were. So we had to look for ways to get back into the sector in concessions to operate hydroelectric plants, or in other kinds of work we’ve done in the past, from construction to fixing vehicles.

We had to create a new generating company that could recover the installations of the old company Luz y Fuerza. That is the cooperative. If the electrical industry went back to the public sector, that would certainly be better. We’d get our contract and our jobs back. But the cooperative is also an answer for us. In generation, we were forced into an alliance with a group of Portuguese investors. But we also have control of some facilities that can directly employ our members, without partners. These are small plants, but the construction of new plants that could generate more power. A lot depends on whether the new government decides to finance this project.

In 2019, providers other than the CFE will be able to purchase blocks of energy and sell it to consumers in Mexico City. When this happens, we are planning to set up a project called Subase. We already have trained people who've done this job for years. We know the management systems. That could reintegrate 2,000 workers.

Electricity rates have gone up 700%, and there’s great dissatisfaction with CFE's service provided. It cuts off service to people too poor to pay. The members of SUTERM working for the CFE just come and cut their power. People angry about this have been organizing with us in the National Assembly of Electricity Users. They’ve declared a strike in payments to the CFE. Membership in the Assembly is now up to 60,000, and we’ve filed a complaint with the Federal prosecutor for consumer affairs.

Eduardo García (Photo by David Bacon)

Despite an agreement with the government, regaining control of the facilities of the former company Luz y Fuerza was not automatic. In fact, workers had to force their way in, and then rebuild what they found, as the president of the cooperative, Eduardo García, explains:

We had to force our way into this worksite [speaking about the large facility of several acres where the coop’s offices are located]. We had a court order saying they had to turn it over, but the CFE refused to let us in. In our 103 years as a union, we’ve learned how to deal with things like that. We put ladders up against the wall, distracted the guards, and then opened up the main gate. We’ve learned in this country that workers’ rights can only be won through struggle and resistance, not because the government gives something to us.

After we recovered our workplaces, and went inside, we had to rebuild everything. It took a lot of work. We had to learn how to bid on jobs, and we are now offering over 500 different services, from cleaning offices to building generation stations. We have more than 400 engineers. We have about 4,000 people who can work on live lines, and we run generation plants, and install photovoltaic cells. We’re even setting up a dining hall because we have chefs in the union, and a textile department that makes our uniforms. We’re all cooperating so that we can go back to the kind of work we did before.

As the exchange in López Obrador's press conference makes clear, the relationship between these two old allies is not going to develop without obstacles and frustrations. SME members were among López Obrador's strongest allies when he was mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2005. When he ran for President in 2006, and was then denied victory by electoral fraud, SME members heeded his call to occupy Mexico City’s main thoroughfare, the Reforma, in tents for months. And although the SME, because of its rules about political independence, did not endorse his 2018 presidential campaign, the union’s members were overwhelmingly supportive.

In his speech to the Mexican Congress, and later to the public in the capital’s Zocalo, López Obrador, promised to halt the privatizations and reverse reforms he characterized as 36 years of neoliberal policies. Reestablishing the state-owned Luz y Fuerza is not likely, however. And as Montes de Oca points out, keeping the current electrical network operated by the CFE solvent and in the public sector will be a challenge.

Two members of the SME cooperative, Luz y Fuerza. (Photo by David Bacon)

SME members could be rehired by the CFE into the jobs they did before 2009, as the scuttled deal with Blake Mora would have provided. The new labor legislation already in the Mexican Congress, initiated by Lopez Obrador's party Morena, would allow the SME’s existence inside the CFE, perhaps eventually even challenging the SUTERM’s right to represent all workers in the enterprise. That would shift the politics in Mexican labor sharply to the left.

In the short term, however, the main issue will be the level of support the López Obrador administration will give to the Luz y Fuerza cooperative. Contracts to help build and operate solar and wind farms, and new direct-current transmission lines bringing the power to Mexican cities, would create many jobs for SME’s members. Putting up a roadblock to that was perhaps one motivation for the accusations of corruption in Rosa Elena Soto's question in the press conference, and for the controversy now grabbing headlines in the Mexican press.

David Bacon is a California writer and photographer, and former union organizer. He has written about Mexican labor and politics for 30 years. He is the author of The Children of NAFTA (UC Press, 2004), The Right to Stay Home (Beacon Press, 2013), and most recently In the Fields of the North / En los campos del norte (Colegio de la Frontera Norte and UC Press, 2017).

Spread the word