A retired Air Force auditor — we’ll call him Andy — tells a story about a thing that happened at Ogden Air Force Base, Utah. Sometime in early 2001, something went wrong with a base inventory order. Andy thinks it was a simple data-entry error. “Someone ordered five of something,” he says, “and it came out as an order for 999,000.” He laughs. “It was probably just something the machine defaulted to. Type in an order for a part the wrong way, and it comes out all frickin’ nines in every field.” Nobody actually delivered a monster load of parts. But the faulty transaction — the paper trail for a phantom inventory adjustment never made — started moving through the Air Force’s maze of internal accounting systems anyway. A junior-level logistics officer caught it before it went out of house. Andy remembers the incident because, as a souvenir, he kept the June 28th, 2001, email that circulated about it in the Air Force accounting world, in which the dollar value of the error was discussed.

Wanted to keep you all informed of the massive inventory adjustment processed at on Wednesday of this week. It isn’t as bad as we first thought ($8.5 trillion). The hit . . . $3.9 trillion instead of the $8.5 trillion as we first thought.

The Air Force, which had an $85 billion budget that year, nearly created in one stroke an accounting error more than a third the size of the U.S. GDP, which was just over $10 trillion in 2001. Nobody lost money. It was just a paper error, one that was caught.

“Even the Air Force notices a trillion-dollar error,” Andy says with a laugh. “Now, if it had been a billion, it might have gone through.”

Years later, Andy watched as another massive accounting issue made its way into the military bureaucracy. The Air Force changed one of its financial reporting systems, and after the change, the service showed a negative number for inventory — everything from engine cores to landing gear — in transit.

This suspicious number is still there. You can see a sudden spike in the Air Force’s working-capital fund’s stagnant spare-parts numbers. It was $23.2 billion in 2015, $23.3 billion in 2016, $24.4 billion in 2017, and then suddenly $28.8 billion in September 2018.

That doesn’t mean money was lost, or stolen. It does, however, mean the Air Force probably has less inventory on hand than it thinks it does.

Now retired, Andy sometimes visits his neighborhood library, which uses RFID smart labels, or radio frequency identification, allowing it to know where all its books are at all times.

Meanwhile, the Air Force, which has a $156 billion annual budget, still doesn’t always use serial numbers. It has no idea how much of almost anything it has at any given time. Nuclear weapons are the exception, and it started electronically tagging those only after two extraordinary mistakes, in 2006 and 2007. In the first, the Air Force accidentally loaded six nuclear weapons in a B-52 and flew them across the country, unbeknownst to the crew. In the other, the services sent nuclear nose cones by mistake to Taiwan, which had asked for helicopter batteries.

“What kind of an organization,” Andy asks, “doesn’t keep track of $20 billion in inventory?”

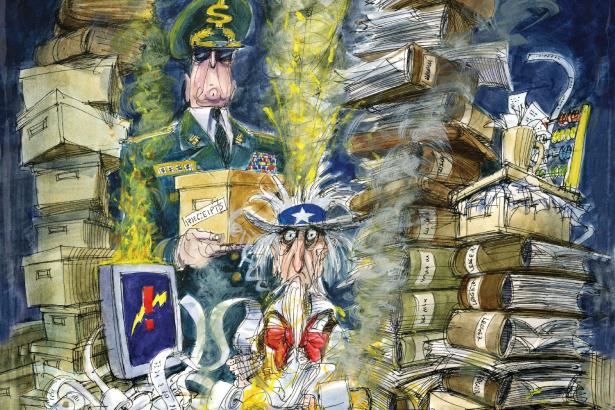

Despite being the taxpayers’ greatest investment — more than $700 billion a year — the Department of Defense has remained an organizational black box throughout its history. It’s repelled generations of official inquiries, the latest being an audit three decades in the making, mainly by scrambling its accounting into such a mess that it may never be untangled.

Ahead of misappropriation, fraud, theft, overruns, contracting corruption and other abuses that are almost certainly still going on, the Pentagon’s first problem is its books. It’s the world’s largest producer of wrong numbers, an ingenious bureaucratic defense system that hides all the other rats’ nests underneath. Meet the Gordian knot of legend, brought to life in modern America.

AT THE TAIL end of last year, the Department of Defense finally completed an audit. At a cost of $400 million, some 1,200 auditors charged into the jungle of military finance, but returned in defeat. They were unable to pass the Pentagon or flunk it. They could only offer no opinion, explaining the military’s empire of hundreds of acronymic accounting silos was too illogical to penetrate.

The audit is the last piece in one of the great ass-covering projects ever undertaken, also known as the effort to give the United States government a clean bill of financial health. Twenty-nine years ago, in 1990, Congress ordered all government agencies to begin producing audited financial statements. Others complied. Defense refused from the jump.

It took a Herculean legislative effort lasting 20 years to move the Pentagon off its intransigent starting position. In 2011, it finally agreed to be ready by 2017, which turned into 2018, when the Department of Defense finally complied with part of the law ordering “timely performance reports.”

Last November 15th, when the whiffed audit was announced, Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan said it was nothing to worry about, because “we never expected to pass it.” Asked by a reporter why taxpayers should keep giving the Pentagon roughly $700 billion a year if it can’t even “get their house in order and count ships right or buildings right,” Shanahan quipped, “We count ships right.”

This was an inside joke. The joke was, the Pentagon isn’t so hot at counting buildings. Just a few years ago, in fact, it admitted to losing track of “478 structures,” in addition to 39 Black Hawk helicopters (whose fully loaded versions list for about $21 million a pop).

That didn’t mean 478 buildings disappeared. But they did vanish from the government’s ledgers at some point. The Pentagon bureaucracy is designed to spend money quickly and deploy troops and material to the field quickly, but it has no reliable method of recording transactions. It designs stealth drones and silent-running submarines, but still hasn’t progressed to bar codes when it comes to tracking inventory. Some of its accounting programs are using the ancient computing language COBOL, which was cutting-edge in 1959.

“These systems,” as one Senate staffer puts it, “were not designed to be audited.”

If and when the defense review is ever completed, we’re likely to find a pile of Enrons, with the military’s losses and liabilities hidden in Enron-like special-purpose vehicles, assets systematically overvalued, monies Congress approved for X feloniously diverted to Program Y, contractors paid twice, parts bought twice, repairs done unnecessarily and at great expense, and so on.

Enron at its core was an accounting maze that systematically hid losses and overstated gains in order to keep investor money flowing in. The Pentagon is an exponentially larger financial bureaucracy whose mark is the taxpayer. Of course, less overtly a criminal scheme, the military still churns out Enron-size losses regularly, and this is only possible because its accounting is a long-tolerated fraud.

We’ve seen glimpses already. The infamous F-35 Joint Strike fighter program is now projected to cost the taxpayers $1.5 trillion, roughly what we spent on the entire Iraq War. Overruns and fraud from that program alone are currently expected to cost taxpayers about 100 times what was spent on Obama’s much-ballyhooed Solyndra solar-energy deal.

Meanwhile, the Defense Department a few years ago found about $125 billion in administrative waste, a wart that by itself was just under twice the size of that $74 billion Enron bankruptcy. Inspectors found “at least” $6 billion to $8 billion in waste in the Iraq campaign, and said $15 billion of waste found in the Afghan theater was probably “only a portion” of the total lost.

Even the military’s top-line budget number is an Enron-esque accounting trick. Congress in 2011 passed the Budget Control Act, which caps the defense budget at roughly 54 percent of discretionary spending. Almost immediately, it began using so-called Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), a giant second checking account that can be raised without limit.

Therefore, for this year, the Pentagon has secured $617 billion in “base” budget money, which puts it in technical compliance with the Budget Control law. But it also receives $69 billion in OCO money, sometimes described as “war funding,” a euphemistic term for an open slush fund. (Non-defense spending also exceeds caps, but typically for real emergencies like hurricane relief.) Add in the VA ($83 billion), Homeland Security ($46 billion), the National Nuclear Security Administration ($21.9 billion) and roughly $19 billion more in OCO funds for anti-ISIS operations that go to State and DHS, and the actual defense outlay is north of $855 billion, and that’s just what we know about (other programs, like the CIA’s drones, are part of the secret “black budget”).

In a supreme irony, the auditors’ search for boondoggles has itself become a boondoggle. In the early Nineties and 2000s, the Defense Department spent billions hiring private firms in preparation for last year. In many cases, those new outside accountants simply repeated recommendations that had already been raised and ignored by past government auditors like the Defense inspector general.

After last year’s debacle, the services are now spending even more on outside advice to prepare for the next expected flop. The Air Force alone just awarded Deloitte up to $800 million to help the service with future “audit preparation.” The Navy countered with a $980 million audit-readiness contract spread across four companies (Deloitte, Booz Allen Hamilton, Accenture and KPMG).

Taxpayers, in other words, are paying gargantuan sums to private accounting firms to write reports about how previous recommendations were ignored.

It’s all a Catch-22 story about a country trapped in an endless cycle of avoidable financial disaster. Each time we try to fix leaks, we end up back where we started, staring at even bigger numerical representations of failure.

For instance, part of what inspired original investigations into defense finances were infamous stories in the 1980s and early Nineties about the military charging $640 for toilet seats, $436 for hammers, etc. A chief crusader was a young Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley, who was so determined to hear such tales from famed military whistle-blower Franklin C. “Chuck” Spinney — one of the first military analysts to go public with accusations of waste and procurement fraud — that early in 1983 Grassley drove to the Pentagon in an orange Chevette to see him.

The DoD refused to let Grassley see Spinney. Grassley got him to testify on the Hill six weeks later.

“The following Monday, his photo was on the cover of Time magazine,” Grassley recalls. The March 1983 cover asked, are billions being wasted?

With the deadline looming to pass a spending bill to fund the government by week's end, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, and other senators gather for weekly strategy meetings on Capitol Hill in WashingtonCongress Budget Battle, Washington, USA - 05 Dec 2017

“A long time after I leave the Senate, [Pentagon spending] will be the same problem,” says Senator Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa. Photo credit: J Scott Applewhite/AP/REX/Shutterstock

It seemed like a breakthrough. Spinney’s tales of waste became symbols that aroused the imagination of both the left and the right, who each saw in them their own vision of government run amok.

But 35 years later, Chuck Grassley, now 85, is still sending letters to the Pentagon about overpriced parts, only this time with more zeros added. The Iowan last year asked why we were spending more than $10,000 apiece for 3D printed airborne toilet-seat covers, or $56,000 on 25 reheatable drinking cups at a brisk $1,280 each (apparently an upgrade to earlier iterations of $693 coffee cups, whose handles broke too easily). The DoD has since claimed to have fixed these problems.

Asked if he was frustrated that it’s the same stories decades later, Grassley says, “Absolutely.” He pauses. “And a long time after I leave the Senate, it’ll likely still be the same problem.”

Three decades into the effort to pry open the Pentagon’s books, it’s not clear if we’ve been going somewhere, or we’ve just been spending billions to get nowhere, in one of the most expensive jokes any nation has played on itself. “When everything’s always a mystery,” says Grassley, “nothing ever has to be solved.”

THIS STARTED with an accident.

“The only reason the audit is happening,” says Sheila Weinberg, CEO of the watchdog group Truth in Accounting, “is because an accountant got sent to Congress.”

In 1985, a brusque Italian-Albanian named Joe Dio-Guardi ran as a Republican for a House seat in New York’s 20th District.

DioGuardi was the son of an immigrant grocer. Before he went on to a Jesuit education at Fordham, his schooling came in the aisles of his father’s store. “I was trained in stock,” DioGuardi says today. “You learn value if you end up chasing someone down the streets of the Bronx if they steal a box.”

In his teen years he went on to be a waiter at Westchester country clubs. He’d watch chefs steal steaks out of the kitchen at the end of every year, knowing that “these rich people . . . if there was a deficit, they would just kick it in at the end of the year.”

From waiting tables he went on to spend 22 years as an accountant at Arthur Andersen, among other things diving into New York City’s financial collapse in the Seventies. He recalls the city still listed buildings that had burned down as current assets. “I learned a lot about the difference between public and private accounting,” he remembers.

In the mid-Eighties, he ran as a Republican for Congress in a Westchester district. It was considered a safe blue seat, with Democrats outnumbering Republicans. He calls himself “the accidental congressman,” because “if my party knew I would win, they wouldn’t have put me up. I was a sacrificial lamb.”

But in a preview of cross-party populist currents, he did win, in part by highlighting his working-class ethnic background, trumpeting his accounting credentials, and sounding bipartisan themes about cleaning up corruption. He promised to “illuminate the dark fiscal corners” of the federal bureaucracy.

In Washington, DioGuardi was horrified by the federal government’s “smoke and mirrors” budgeting. He told fellow Republicans the techniques Congress used would get private-sector officers “sent to jail.”

“Joey the Waiter,” who is 78 today, still has the same tough-talking New York personality he had as a candidate. It’s easy to laugh imagining how his insistent Bronx demeanor was received by some of his more upper-crust and genteel colleagues back then. It would explain why he was first ignored when he began writing legislation to force the government to undergo the kind of auditing that’s mandatory in the private sector.

But when the savings-and-loan crisis plunged America into a financial scare in the late Eighties, “fiscal responsibility” became a political catchword. Instantly, “Joey the Waiter” was in demand. “Suddenly, everyone was like, ‘Where’s that bill DioGuardi wrote?’ ” he recalls.

He found diverse allies in a pair of Democrats, Sen. John Glenn and Rep. John Conyers. Together they authored what would ultimately be called the “Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990.”

The legislation forced government agencies to name a CFO, conduct audits and create “modern federal financial management structure.” Twenty-three agencies, from Defense to Labor to State, were ordered to begin submitting “department-wide annual audited financial statements” by 1994.

Although there were regulations over the years requiring various forms of financial reporting, nothing like a full-scale federal audit had ever been attempted. Incredibly, from an accounting perspective, the U.S. government had remained essentially virgin territory for centuries.

As far back as 1787, the Constitution mandated “a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.” But no independent examiner had ever fully checked the government’s books. By the late Eighties and early Nineties, hundreds of billions of tax dollars were being spent annually, and no one really knew where. To DioGuardi, the situation was outrageous.

“It’s a constant principle in history, from the Medicis to today,” says DioGuardi. “If no one’s watching the money, there will be bankruptcies.”

THE CFO Act at least introduced the idea that someone was supposed to be watching. By 1997, Cabinet-level departments like Labor, Agriculture and Commerce were submitting financial reports. In the first year, only six were able to pass. Within a few years, however, most were in compliance. By 2013, Defense was the only federal agency that had not submitted a financial statement.

One of the main reasons the military wasn’t submitting numbers was it didn’t have them. The Pentagon every year employs an accounting shortcut that should make more sense to civilians at this time of year, because it’s similar to what the roughly six percent of Americans who cheat on taxes do annually.

Taxpayers who think they’re owed deductions, but don’t have the receipts to back up their expenses, will sometimes take a rough guess, maybe based on what their prior-year deductions were. Then they file returns infected with guesses, “plugged” in to look like deductions counted up honestly.

The Pentagon does basically the same thing, only on a galactic scale. At the end of every year, it submits a “Budget execution request” that includes complete month-by-month statements of that year’s spending.

The White House will then take these numbers and use them to project a defense budget for the following year. The president submits that budget to Congress, which in turn will actually appropriate the money. Almost without exception, the Pentagon ends up getting a raise. For 2019, Donald Trump submitted a budget that asked for $716 billion, or $82 billion more than the Department of Defense received the previous fiscal year.

The system makes sense, except for one problem: The financial reports the Pentagon submits are faked.

The Defense Department, for the most part, does not know how much it spends. It has a handle on some things, like military pay, but in other places it’s clueless. None of its services — Navy, Air Force, Army, Marine Corps — use the same system to record transactions or monitor inventory. Each service has its own operations and management budget, its own payroll system, its own R&D budget and so on. It’s an empire of disconnected budgets, or “fiefdoms,” as one Senate staffer calls them.

Instead of using a single integrated financial accounting system that would maintain a global picture of its finances at all times, the Pentagon built another bureaucracy to pile atop the others, called the Defense Finance and Accounting Service, or DFAS. Created by then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney in 1991, DFAS is in charge of collecting financial reports from all the different fiefdoms at the end of each month. DFAS is like a tribune traveling on horseback at month’s end, collecting a pile of scrolls from each castle.

In 2013, Reuters published a brutal exposé showing how DFAS accountants conducted a mad scramble at the end of each month to try to piece together records of transactions to justify spending. But in thousands of cases a month, no records existed. “We didn’t have the detail,” one accountant explained.

Complicating matters is the fact that money is allocated to the military on different schedules. If Congress gives the Navy $53 billion for operations and maintenance, as it did this year, the service is expected to spend all that money that year. Such expenses — payroll is another — are called “one-year money.” Meanwhile, research and development might be “two-year money,” and contracting might be “five-year money.”

Aerial View of the Pentagon from a commercial airliner taking-off from Reagan National Airport outside Washington, DC.Aerial Views of the Pentagon, Washington DC, USA - 17 Feb 2017

There have been multiple cases involving officials taking advantage of flaws in the Pentagon’s system over the years. A civilian secretary bilked the Air Force out of $1.4 million for more than a decade before anyone noticed. Photo credit: REX/Shutterstock

If the Pentagon doesn’t spend all the money in exactly the amounts Congress says it can spend, in the time ordained by Congress — if it doesn’t spend all its one-year money in one year, all its five-year money in five years and so on — the military is supposed to give its unspent money back to Congress.

But the military is never really on time, and constantly commingles its various pots of money. Grassley in the late Nineties found out the military was using a computer program called MOCAS, or Mechanization of Contract Administration Services, to help speed this commingling. Whenever the Pentagon had bills to pay, instead of just drawing the money from the right account, MOCAS would sometimes try to spend “old money” first, i.e., from whatever funds were about to expire.

It’s illegal for any government agency to spend money appropriated for one purpose on a different program. But the military — either hilariously or horribly, depending on your perspective — created a program that algorithmically produced such violations

of the law. They weren’t minor violations: Grassley has fought for years against such automatic payments, saying bureaucrats use them to “avoid violations of the Antideficiency Act — a felony.” Last year’s audit found the Antideficiency Act was one of five laws the agency violated.

MOCAS still exists, but it’s unclear how or if it’s been updated. In any case, Defense still lacks rec-ords showing that it’s paying for the right programs from the right accounts. Out of terror that it might have to return money as a result, the DoD orders its accountants to make numbers fit.

Those DFAS accountants in the Reuters exposé were told by superiors that if they couldn’t find invoices or contracts to prove the various services spent their one-year money and two-year money and five-year money on time, they should execute “unsubstantiated change actions,” i.e., lie.

The accountants systematically “plugged” in fake numbers to match the payment schedules handed down by the Treasury. These fixes are called “journal voucher adjustments” or “plugs.”

As a result, those year-end financial statements will look like they match congressional intentions. In truth, the statements packed with thousands of plugs are fictions, a form of systematic accounting fraud Congress has quietly tolerated for decades.

The fake-number system is such long-accepted practice that it’s acquired numerous dull-sounding names. You’ll see the invented numbers called “forced-balance entries” by the General Accounting Office (which is run by Congress), “adjustments not adequately supported” by the Defense inspector general, and “journal vouchers” or “JVs” or “workarounds” by the Pentagon’s own comptroller general. On the Hill, everyone refers to “plugs.”

There are innocent explanations for plugs, although even the best excuse is still incompetence. For example, if the Navy buys a helicopter from the Army (which is the “item manager” in charge of monitoring all rotary-wing aircraft), it will show up as an expense on the books of both services. Although the money has been spent only once, both the Army and the Navy will report the expense.

Instead of canceling out such intramural accounting discrepancies, which is what would happen at any chain of doughnut shops, the Department of Defense never bothered to fix its accounting rules. With hundreds of different acronymic systems, a single error might generate bogus numbers exceeding the transactions’ original value.

This is a generous explanation for news of the sort released by the inspector general in 2016 showing the Army — with an annual budget of $122 billion — generated accounting plugs 54 times that amount, a full $6.5 trillion worth, in 2015 alone.

When civilian analysts see these numbers, they always first assume they’re typos, because no company could survive such gargantuan accounting snafus.

“When I saw that 6.5 trillion number for the first time, I thought it had to be a mistake,” says Michigan State University professor Mark Skidmore, who in 2017 led a study that discovered $21 trillion in plugs over a 17-year period. “I thought it was maybe 6 billion. But it’s really 6 trillion.”

As these stories leaked out to the public, the huge numbers became (mostly misunderstood) talking points on social media. New Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for instance, cited Skidmore’s study and tweeted that two-thirds of a $32 trillion proposed price tag for Medicare for All “could have been funded already” by the Pentagon.

Ocasio-Cortez didn’t have it quite right. Skidmore’s $21 trillion figure doesn’t mean that much money was wasted, or is sitting in a Swiss account somewhere. The Pentagon didn’t even receive that much money during the time period in question.

Moreover, some of the plugs are adjustments upward and some downward. If they were ever netted out — no one has ever tried — the size of the accounting hole might be smaller.

However, according to Andy and others, the $21 trillion figure may undercount the accounting errors in the system, as some plugs are both automated and unidentified. What’s clear is that the ubiquitous plugging and quantity of bad numbers in the Pentagon’s books are so massive that it will take a labor of the ages to untangle.

All of this is difficult to follow, but the key is that when a suspicious number pops up anywhere in the military’s multiple accounting silos, it typically isn’t investigated, but simply fixed on paper and sent on its way. In a private company, if inventory numbers suddenly jumped by a few billion dollars in one month, auditors would swarm warehouses in search of the problem.

The military can’t say the same. This was one of the things auditors found last year, that the Pentagon lacked “policies and procedures to confirm the existence of government property in possession of contractors.” This is a fancy way of saying the Pentagon doesn’t send inspectors to make sure Lockheed-Martin or Boeing or whoever still have parts they say they’re repairing or maintaining.

This, ultimately, is the conclusion of the audit. We don’t have anything like a full picture of what waste and abuse might be hidden under those plugs, though we have an idea (see sidebar).

We do, however, know the Pentagon’s books are so choked with bad data that discovering abuses in real time is virtually impossible. Compound that with decades of cuts to the Pentagon’s staff of criminal investigators and you have an open invitation to crime. Invoices could be systematically inflated for decades and no one would know. As Andy the Air Force accountant puts it, the system is “desensitized to fraud.”

IF YOU ASK congressional staffers why the plugging system is permitted, they just shrug. Congress really has only two ways to respond when the DoD breaks the law. Elected officials can shout and criticize the Pentagon, or withhold funds. The former is not terribly effective, and the latter has so far proved politically impossible.

“No other federal agency could get away with this,” is how one Senate staffer puts it.

The military has been told repeatedly to stop plugging and develop more rational accounting systems. In case after case, reforms compounded problems.

One of the first fixes was aimed at the infamous toilet seats and hammers. The General Accounting Office in 1992 issued a report blasting the military for “poor cost estimating” and suggested changes. The result was the invention of a creature called the “prime vendor,” basically a middleman with the power to set prices and choose subcontractors.

This system only inflated prices. By 2004, Defense was spending $7.4 billion annually on prime-vendor purchases, after spending $2.3 billion in 2002.

Knight-Ridder newspapers got wind of this and in 2005 reported the military was now buying 85-cent ice trays from prime vendors for $20 apiece. Within a month, a refrigerator for a C-5 airplane was being dragged on the floor of a House hearing and a Navy admiral named Keith Lippert was being asked by California’s Duncan Hunter — not exactly a pillar of rectitude himself — to explain why he’d bought nine fridges from a prime vendor for $32,642.

Over the years, this pattern repeated itself. An attempt to standardize the military’s payroll and personnel records system, called DIMHRS, took 12 years and cost more than $1 billion before being scrapped. In 2005, the Air Force set out to buy a standardized computer system from Oracle called the Expeditionary Combat Support System. It took seven years and more than $1 billion for that plan to be scrapped. John McCain joked about ECSS, “At least they got the toilet seat. Out of this, they got nothing.”

This same motif held with regard to the military’s promises about “audit readiness.” The Pentagon initially said it would be ready to be audited by 1997. After that date passed with a yawn, Pentagon officials made a series of bold promises.

In 2003, Defense comptroller Dov Zakheim told the House Budget Committee, “We anticipate having a clean audit by 2007.” Soon after disavowing that promise, he said, “The further we dug . . . the more difficulties turned up.”

In 2005, the Pentagon began supplementing its verbal promises with reports called the Financial Improvement and Audit Readiness (FIAR) plan. This report basically told you every year that we were getting closer to sorting all this stuff out. Some excerpts:

December 2005: “Progress has been achieved.” September 2006: “Progress has been made.” September 2007: “Progress has been made in several areas.” March 2008: “Substantial progress has been made.” March 2009: “Significant progress has been made, but much needs to be done.”

President Donald Trump speaks at a hanger rally at Al Asad Air Base, Iraq, . President Donald Trump, who is visiting Iraq, says he has 'no plans at all' to remove US troops from the countryTrump Iraq - 26 Dec 2018

President Donald Trump speaks at a hanger rally at Al Asad Air Base, Iraq. Photo credit: Andrew Harnik/AP/REX/Shutterstock

The Pentagon had been attempting to conduct department-wide audits dating back to 1996. By the mid-2000s, perhaps 100 auditors from the DoD inspector general, plus a hundred or more from the various services, were annually trying to create a single financial statement, despite an almost complete lack of audit-trail information. They made some helpful recommendations, but would never get very far before concluding an audit was not possible.

“We were trying to make chicken soup out of chicken shit,” says an auditor, with a sad laugh.

After nearly 15 years of such exercises, Grassley grew so furious that he introduced an amendment ordering the Pentagon to stop trying to audit itself until it was capable of doing something useful. The amendment passed and lived on as Section 1003 of the 2010 National Defense Authorization Act.

The 2010 NDAA amendment also ordered the Pentagon to actually be ready by 2017. “It was, ‘Start over and get it done,’ ” says Grassley now.

The Grassley amendment stopped the annual mobilization of hundreds of auditors, but didn’t stop the audits completely. The two competing laws — the CFO Act and the 2010 NDAA — created a literal Catch-22, with the services both ordered and not ordered by law to complete audits of themselves.

The services tried to spend their way out of the problem. Incredibly, they began competing to see how much they could blow on audit-readiness programs. In 1997, the Army splurged at least $4 billion on the Global Combat Support System, which the Center for Public Integrity said was designed to centralize a dozen different outmoded accounting systems. The smaller Marine Corps developed its own system with the same name, and dropped $1 billion.

The GAO in 2009 then issued a report complaining $6 billion had already been spent in audit preparation. According to the GAO, it took that much money to get the Pentagon to a place where it could accurately track incoming appropriations.

In 2011, then-Defense comptroller Robert Hale confessed to Congress, “We don’t really fully understand in the Department of Defense what you have to do to pass an audit for military service, because we have never done it.”

Translation: Despite having 60,000 financial-management employees who’d had 21 years to wrap their heads around the task of producing financial statements, Hale admitted none had taken the plunge: “You can’t learn to swim on the beach.”

Speaking of beaches, Hale said he hoped to use the Marine Corps as an accounting “beachhead,” because it was ahead of the other services in terms of auditability. But a 2011 “trial audit” of the Marines ended in catastrophe. The inspector general found it couldn’t account for $2 billion in expenditures. It sounds worse when you consider they were only auditing a $4 billion portion of the Marines’ budget.

The Marines doubled down. In 2014, the Pentagon announced the Corps passed an audit for 2012. The event was so momentous, they marked the occasion in the Pentagon’s Hall of Heroes. Then-Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel was presented with a framed certification of the “clean” opinion. Hagel, a consistent ally of defense, beamed as he said, “We don’t spend a lot of time using big megaphones to tout our great accomplishments. . . . We get the job done.”

But word began to spread that the Marine audit was again a con job. “It was an intellectual exercise in cheating and deception,” says Grassley, whose office was in the middle of the effort to get the inspector general’s office to re-examine the results. Within a year, the inspector general withdrew its approval. “Our opinion on the FY 2012 United States Marine Corps,” it said, “is not to be relied upon.”

Even worse, it then came out that the inspector general’s office was sending emails down the

chain, pressuring auditors to agree with an outside auditing firm, which already had a record of flawed audits of the Marine Corps. This should have been a red flag, according to retired military auditor Jack Armstrong.

“Why wouldn’t you want to train a very close eye when you’ve already had suspicions about the quality of their work?” says Armstrong.

Then-Defense Department comptroller Mike McCord was philosophical about the Marine fiasco. “It’s a learning experience,” he said.

AFTER ALL OF these false starts, it soon became clear that the only way to get the Pentagon to actually fix itself would be if Congress stopped sending money. Starting in 2012, a succession of legislators in both the House and Senate, including Tom Coburn, R-Okla.; Barbara Lee, D-Calif.; Ron Wyden, D-Wash.; Rand Paul, R-Ky.; Bernie Sanders, I-Vt.; and John McCain, R-Ariz., tried to introduce amendments yanking funding if the Pentagon didn’t correct itself.

“None have made it into law,” says Mandy Smithberger of the Project on Government Oversight.

A major problem is campaign finance reform. Ask Hill staffers why it’s hard to pass any bill that even contemplates withholding funding for the Pentagon, and they say you’ll run smack into a bipartisan batch of refuseniks who’ve been gorging on defense-sector campaign contributions, thanks to their status on committees like Armed Services or Appropriations.

“You can’t get the Pentagon to take an audit seriously unless you threaten to stop funding, and you can’t stop funding without campaign finance reform,” says one Hill staffer.

Unfortunately, the annual audit has now created a secondary cash flow for the accounting firms, which have formally entered the family of permanent high-end military contractors like Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Boeing and Raytheon.

The money now flows out in two directions. One estimate puts the annual cost for accounting at about a billion: $400 million a year for the audits by firms like Ernst & Young, and about $600 million for firms like Deloitte to fix problems identified by said audits.

The Pentagon can keep accountants busy forever simply doing the taxonomic job of describing its inauditability. The Defense Department employs 3 million people, has 280 ships, nearly 16,000 planes and 585,000 “facilities” in at least 80 countries. You’ve heard of “too big to fail” — the DoD’s universe is too big to count. “Impossible. . . . We can’t do it. . . . It’s too big,” one exasperated DoD official complained.

“They’re telling us it’s going to get worse before it gets better,” is how one Hill staffer puts it.

If auditors ultimately make sense of all their work, it’s worth it. But they could easily just keep inching toward compliance forever. “For a billion dollars a year,” says Grassley, “you ought to see progress.”

In April 2016, U.S. Comptroller General Gene Dodaro testified before the Senate that the Pentagon had spent up to $10 billion to modernize its accounting systems. Those attempts, he said, had “not yielded positive results.”

Two years later, Sens. Grassley and Sanders, along with Wyden and others, were asking Dodaro in a letter why no progress had been made toward getting those systems in place. “Are you going to finish it in my lifetime?” a Hill staffer is said to have demanded in a meeting with Dodaro. He got no answer.

Sanders last year introduced an amendment to ding the Pentagon for 0.5 percent of its funding until it passes (not takes, but passes) an audit. He failed, but is going to keep trying. For his office, the Pentagon audit issue is as much about misplaced social priorities as it is about waste and mismanagement.

“Over and over again, we’ve been told we cannot afford to guarantee health care as a right, make public colleges tuition-free, or seriously address any of the needs of the working class,” Sanders says. “When it comes to the massive waste, fraud and abuse at the Pentagon, there’s a deafening silence.”

Both Sanders and Grassley have been tilting at the Pentagon windmill for decades now, from opposite ends of the political spectrum. For Grassley, there is a sense of exhaustion.

Asked how much progress has been made toward creating a workable accounting system at the Pentagon, he says, “At my level, I would have to say zero.” He pauses. “Based on the track record, it seems like they don’t want to fix it.”

All this history sums up the conundrum. A Republican waste-hawk like Grassley laments the inability/unwillingness of the Pentagon to implement a modern, corporate-style, unified accounting system, and is convinced there will never be a clean audit until one is developed.

Meanwhile, a progressive like Sanders, who is anxious to dial back Pentagon spending as part of a general rethink of our national priorities, laments the inability/unwillingness of Congress to take the real steps needed to enforce compliance. The system of campaign contributions that keeps key committees captive probably locks this problem in place, until there’s reform on that end.

Both senators, unfortunately, have legitimate concerns. The twin obstacles to a true audit — one logistical, one political — are reasons few on the Hill feel confident a clean opinion is coming anytime soon. As one Hill staffer puts it, “DoD loves to find inefficiencies. It just means more they can spend.” He adds, “Every year, you know they’re going to get that $700 billion. That’s not going to change.”

Until someone passes a law with real teeth, that really threatens cuts of military appropriations, the most likely eventuality is the Department of Defense continuing to take and flunk audits at great expense in perpetuity. At best, each year we may end up getting a conclusion like this one about the 2018 audit, from the Pentagon’s inspector general. “The most important outcome . . . was not the overall opinion,” the IG wrote, “but that . . . the DoD makes progress.”

It’s impossible to overstate the enormity of the problem the DoD’s stalled audit poses. The fact that it can’t pass audit means the entire government is in the same boat. Until the Pentagon gets a passing grade, the whole United States will annually receive what’s called a “disclaimer of opinion” on its finances, which is accounting-ese for “Incomplete.”

DioGuardi, who set all this in motion 30 years ago, says no publicly traded company could issue a bond without passing an audit first. But the U.S. issues hundreds of billions in bonds, despite the gaping hole in its books caused by the endless unresolved problem at the Department of Defense. “From an accounting point of view,” he says, “it’s a horror story.”

“Ernst & Young will eat them alive,” says Andy. “It’s so much worse than people think.”

Just over 50 years ago, Dwight Eisenhower gave his famous farewell address warning of the power of the “military-industrial complex.” The former war commander bemoaned the creation of a “permanent armaments industry of vast proportions,” and said the “potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Eisenhower’s warning is celebrated by the left as a caution against the overweening political power of warmakers, but as we’re now seeing, it was predictive also as a fiscal conservative’s nightmare vision of the future. The military has become an unstoppable mechanism for hoovering up taxpayer dollars and deploying them in the most inefficient manner possible. Schools crumble, hospitals and obstetric centers close all over the country, but the armed services are filling warehouses for some programs with “1,000 years’ worth of inventory,” as one Navy logistics officer recently put it.

It’s the ultimate example of the immutability of the American political system. Even when there’s broad bipartisan consensus, and laws passed, and both money allocated for changes and agencies created to enact them — if the problem is big enough, time bends toward corruption, and chaos always outlasts reform. Eisenhower couldn’t have predicted how right he was.

Matt Taibbi is a contributing editor for Rolling Stone and winner of the 2008 National Magazine Award for columns and commentary. His most recent book is ‘I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street,’ about the infamous killing of Eric Garner by the New York City police. He’s also the author of the New York Times bestsellers 'Insane Clown President,' 'The Divide,' 'Griftopia,' and 'The Great Derangement.'

Spread the word