Lo—TEK. Design by Radical Indigenism

Julia Watson

Taschen

ISBN 978-3-8365-7818-9

Ever since smartphones hooked us with their limitless possibilities and dopamine hits, mayors and city bureaucrats can’t get enough of the notion of smart-washing their cities. It makes them sound dynamic and attractive to business. What’s not to love about whizzkids streamlining your responsibilities for running services, optimising efficiency and keeping citizens safe into a bunch of fun apps?

There’s no concrete definition of a smart city, but high-tech versions promise to use cameras and sensors to monitor everyone and everything, from bins to bridges, and use the resulting data to help the city run smoothly. One high-profile proposal by Google’s sister company, Sidewalk Labs, to give 12 acres of Toronto a smart makeover is facing a massive backlash. In September, an independent report called the plans “frustratingly abstract”; in turn US tech investor Roger McNamee warned Google can’t be trusted with such data, calling the project “surveillance capitalism”.

There are practical considerations, too, as Shoshanna Saxe of the University of Toronto has highlighted. Smart cities, she wrote in the New York Times in July, “will be exceedingly complex to manage, with all sorts of unpredictable vulnerabilities”. Tech products age fast: what happens when the sensors fail? And can cities afford expensive new teams of tech staff, as well as keeping the ground workers they’ll still need? “If smart data identifies a road that needs paving,” she writes, “it still needs people to show up with asphalt and a steamroller.”

Saxe pithily calls for redirecting some of our energy toward building “excellent dumb cities.” She’s not anti-technology, it’s just that she thinks smart cities may be unnecessary. “For many of our challenges, we don’t need new technologies or new ideas; we need the will, foresight and courage to use the best of the old ideas,” she says.

Saxe is right. In fact, she could go further. There’s old, and then there’s old – and for urban landscapes increasingly vulnerable to floods, adverse weather, carbon overload, choking pollution and an unhealthy disconnect between humans and nature, there’s a strong case for looking beyond old technologies to ancient technologies.

It is eminently possible to weave ancient knowledge of how to live symbiotically with nature into how we shape the cities of the future, before this wisdom is lost forever. We can rewild our urban landscapes, and apply low-tech ecological solutions to drainage, wastewater processing, flood survival, local agriculture and pollution that have worked for indigenous peoples for thousands of years, with no need for electronic sensors, computer servers or extra IT support.

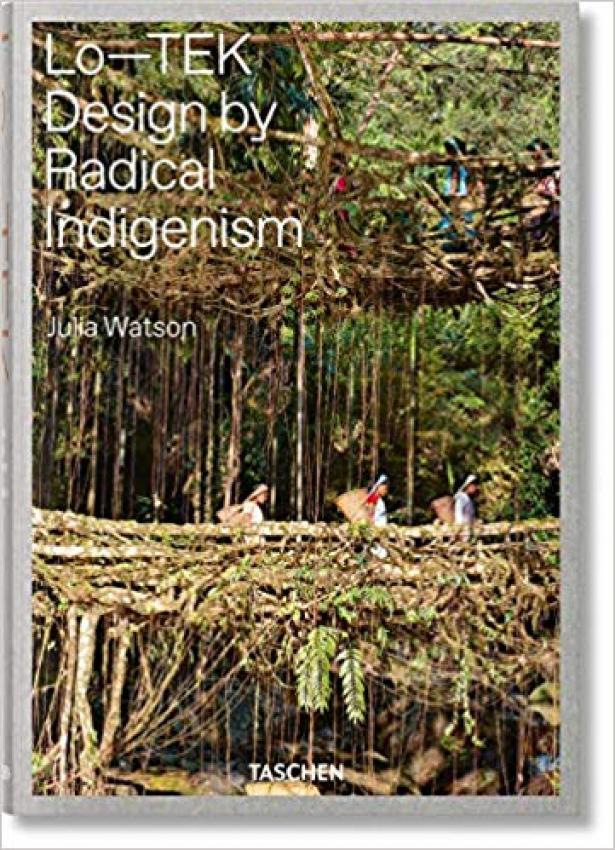

This month, Julia Watson, a lecturer in urban design at Harvard and Columbia Universities, launched her book Lo-Tek: Design by Radical Indigenism, with publisher Taschen. It’s the result of more than 20 years of travelling to research the original smart settlements, through an architect’s lens.

She visited the Ma’dan people in Iraq, who weave buildings and floating islands from reeds; the Zuni people in New Mexico, who create “waffle gardens” to capture, store and manipulate water for desert crop farming; and the subak rice terraces of Bali. Watson walked the living tree-root bridges that can withstand adverse weather better than any human-made structure, and that allow the Khasi hill tribe in Northern India to travel between villages during the monsoon floods.

“There are so many different ways you can rewild cities,” says Watson – and it’s not just a case of plonking an ancient system in a city, but rather adapting complex ecosystems for different types of places with their own unique requirements. Take a current proposal she is working on for the high-rise city of Shenzhen on the Pearl River estuary by Hong Kong. It was once a fishing village, then a textile town, “and it just skyrocketed,” says Watson. “All of the fishponds and polders and dykes and wetlands that absorb all the water in that delta landscape are being erased. So the city is developing in a way that’s erasing the indigenous resilience in the landscape.”

But you don’t have to erase to go forwards, she says. “You can leapfrog and embed local intelligence, using a nature-based traditional Chinese technology that’s climate resilient, ecologically resilient and culturally resilient. And we can make beautiful urban spaces with them as well.”

Kongjian Yu, a design professor at Peking University, agrees with this philosophy. Known as the “sponge cities” architect, Yu creates urban landscapes in China that passively absorb rainwater, using permeable pavements, green roofs and terraced wetland parks that flood during monsoon. If wetlands are situated upriver of the buildings, they will flood before the water reaches the city proper.

The parks have brought fish and birds back to cities, says Yu, “and people love it.” The projects, he says, “are performing well, and many of them have been tested for over 10 years, and can certainly be replicable in other parts of the world.” In fact, this month he has visited Bangladesh, ironically, “helping their ‘smart city’ project,” where he has convinced “the minister in charge that nature is smart, and our ancient wisdom tells us how to live with nature in a smart way.”

Copenhagen, too, has opted for a dumb – or, as local planners call it, “a green and blue” – solution to their increasing flood risks: namely, a series of parks that can become lakes during storms. The city estimated they would cost a third less than building levees and new sewers, and come with the added ecological benefits of rewilding. An abandoned military site was cleaned up in 2010 and rewilded into a nature reserve and common for grazing animals, the Amager Nature Centre – a vast park with not only happy people meandering and cycling around but insects, protected amphibians, rare birds and deer.

Or, as waters rise globally, we can learn from Makoko, the incredible city-on-stilts in Lagos that is home to 80,000 residents. Its “floating school” – sustainable and solar-fuelled – has captured the world’s imagination. Rotterdam has already introduced a floating forest and farm, and is developing plans for a sustainable floating city.

The Eastgate building in Harare has no air-conditioning or heating, yet stays regulated all year round using a design inspired by indigenous Zimbabwean masonry and termite mounds. Photograph: Ken Wilson-Max/Alamy

As for dumb transport, there can be no doubt that walking or cycling are superior to car travel over short urban distances: zero pollution, zero carbon emissions, free exercise.

And there’s a dumb solution to the spread of air conditioning, one of the greatest urban energy guzzlers: more plants. A study in Madison, Wisconsin found that urban temperatures can be 5% cooler with 40% tree cover. Green roofs with high vegetation density can cool buildings by up to 60%. Or you could just think like a bug: architects are mimicking the natural cooling airflows of termite burrows. Mick Pearce’s 350,000 sq ft Eastgate Centre in Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare, completed in the 1990s, is still held up as a paragon of dumb air conditioning: all it needs are fans, and uses a tenth of the energy of the buildings next door.

A few token green walls and trees won’t do it. Watson calls for a focus on permaculture: self-sustaining ecosystems. “If it’s an urban forest,” she says, “perhaps it’s in the centre of the city, perhaps it’s on the periphery, or it could be an interior environment – an atrium designed to have a complex ecosystem that’s also agriculturally productive.”

Could living root bridges similar to those used by the Khasi hill tribe be grown in urban settings? Photograph: Amos Chapple

There are hundreds of nature-based technologies that have never been explored. For example, Watson envisions stunning urban uses for the living root bridges of the Khasi hill tribe: “They could be grown to reduce the urban heat island effect by increasing canopy cover along streets, with roots trained into trusses that integrate with the architecture of the street – in essence, removing the distinction between tree and building.” They could even retain their original use during seasonal floods – living, physical bridges over the water.

In April, Greta Thunberg and Guardian columnist George Monbiot made a rallying video calling for more trees and wetlands and plant cover to tackle the climate crisis. Cities can be part of this push.

The idea of smart cities is born of what Watson describes as “the same human superiority-complex that thinks nature should be controlled”. What’s missing is symbiosis. “Life on Earth is based upon symbiosis,” Watson says. She suggests we replace the saying “survival of the fittest” with “survival of the most symbiotic”. Not as catchy, perhaps. But smarter.

Spread the word