“Whites Only Within City Limits After Dark” reads the faded road sign, an artifact on display at the Tubman African American Museum in Georgia. The sign was found outside one of Connecticut’s sundown towns.

Sundown towns were municipalities that prevented African-Americans or other minorities from lingering after dark.

Beginning in the 1890s, New England’s small towns and rural communities drove African-Americans into urban ghettoes, Loewen contends.

Small towns kept out not just black people, but Jews, Catholics, Greeks, Italians, Indians, even trade unionists and gays. They used violence and intimidation and restrictive covenants and mortgage practices

Great Migration

Some New England counties drove out their entire African-American populations. From 1890 to 1940, many African Americans who lived in rural areas of New England had to move to cities.

From 1890 to 1930, the U.S. black population increased 60 percent. Between 1915 and 1930, more than a million African-Americans moved from the South to the North. And yet entire counties in New England became whiter.

In Maine, for example, only two of the state’s 16 counties had fewer than 10 blacks in 1890. By 1930, Maine had five.

Writes Loewen, in Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, 14 Maine counties had at least 18 African Americans. By 1930, only nine did. Five black people lived in Lincoln County in 1930, where 26 had lived in 1890. Hancock County had 30,000 people in 1930, but only three were black. Forty years earlier, there had been 56.

Vermont had no all-white counties until 1930. New Hampshire had no all-white counties in 1890, but two in 1930.

Rise of the Klan

Keeping out African-Americans happened well before the 19th and 20th century. In 1717, Town Meeting in New London, Conn., voted against free blacks living in the town or owning land anywhere in the colony.

But in the 1890s, racism deepened in the North as memories of the Civil War faded. Waves of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from Canada and southern Europe moved into Yankee mill towns. The influx of immigrants sparked the revival of the Ku Klux Klan — and created sundown towns.

In the early 1920s, the Klan began to hold regular meetings and cross-burnings in small towns in eastern and central Massachusetts. A Klan rally near Montpelier, Vt., in 1925 drew 10,000.

The Klan in London, Ontario

The Klan spread rapidly in Maine, with 15,000 showing up at the state convention in 1923. The KKK held its first daylight parade in the United States in Milo, Maine, in 1923, and others soon followed.

In 1925, The Washington Post estimated New England had more than a half-million Klansmen, with 150,141 in Maine and more than 370,000 across the other New England states.

Though Klan membership fell almost as quickly as it grew in New England, the KKK left a legacy of sundown towns. Their history is rarely told.

Tales of Sundown Towns

Loewen collected anecdotes about places where minorities were afraid to spend the night.

- Italian stonecutters who quarried in Portland, Conn., were told to be on the other side of the Connecticut River by sundown. The bridge would then stay open at night so no one could pass over it.

- One resident of the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy, Mass., remembers an incident from the mid-1950s: “My father, a jazz musician, had some of his musician friends over one night for some jamming. Most of the musicians involved were black. The next day, a delegation of neighbors…came by to register their disapproval that my father had blacks in their neighborhood after dark.”

- A similar story was told about Burlington, Conn. An African-American family friend from Waterbury came over to play cards. “He always made a habit of leaving before sunset and if he could not, he would spend the night on the couch. … earlier years, whenever he would drive in or out of town, the police would stop and harass him, detain him for questioning, or pull him over and run his license and plates. Comments were made to the effect that being a black man in Burlington after dark, he couldn’t be up to any good…”

Starting in the 1930s, the Negro Motorist Green Book guided African-American travelers away from sundown towns. Black travelers typically carried blankets, food and cans of gasoline in their cars to avoid embarrassment, or worse.

Restrictive Covenants

In 1905, restrictive covenants began appearing in property deeds. They typically stated, “No portion of these premises shall ever be sold to or occupied by anyone other than members of the white or Caucasian race.” Then they often added, “Nothing in the foregoing shall preclude live-in servants.”

A 1940 deed for a development called High Ledge Homes in West Hartford, Conn., said, “No person of any race except the white race shall use or occupy any building on any lot.” The deed allowed one exception for people of a different race: the owner’s employees.

Similarly, Manchester-By-The-Sea in Massachusetts only allowed blacks and Jews to live within its borders if they were servants.

Government-Supported Sundown Towns

The federal government encouraged sundown towns through discriminatory mortgage practices. Between 1934 and 1968, 98 percent of loans approved by the federal government in Connecticut went to white, non-Hispanic borrowers.

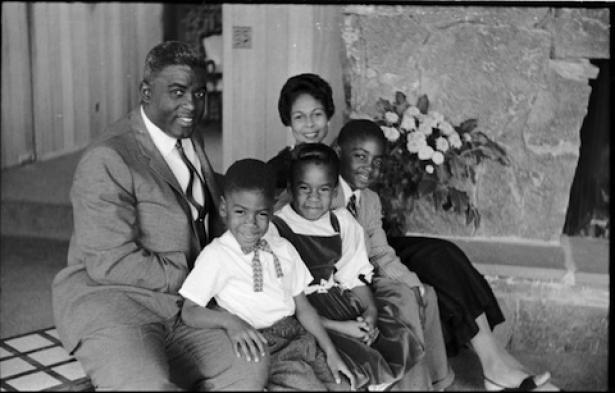

In 1954, baseball great Jackie Robinson bought a house in Stamford, Conn., but only with help from prominent white people. He proved the exception in suburban New England.

In Nahant, Mass., a property deed written in the 1920s contained language forbidding the owner to sell the house to Greeks or Jews. (Nahant, ironically, now has the densest population of Greek descendants in New England.)

Anti-Semitism

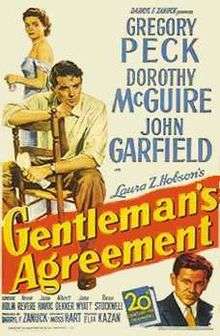

A film that exposed Darien as one of Connecticut’s sundown towns.

In 1922, the Sharon, Conn., chamber of commerce distributed a leaflet asking homeowners not to sell to Jews. Another realtor in Greenwich, Conn., sent a similar memo. It said, “From this date on, when anyone telephones us in answer to an ad in any newspaper and their name is, or appears to be Jewish, do not meet them anywhere.”

Darien, Conn., did not let Jews spend the night within its borders. The 1947 film Gentleman’s Agreement , co-starring Paul Revere’s descendant Anne Revere. exposed the practice. Gregory Peck played a reporter pretending to be Jewish to write a story on anti-Semitism.

The Civil Rights movement then started to change all that with laws against racist policies. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited housing discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, family status or national origin.

But attitudes didn’t necessarily change.

In 1973, all-white Ashby, Mass., voted at Town Meeting 148 to 79 against inviting people of color into town.

Photos: Darien, Conn., via Wikimedia. This story about sundown towns was updated in 2020. With thanks to Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism by James Loewen.

Spread the word