For nearly thirty-five years, Gil Green was my mentor, surrogate father, personal hero, favorite teacher, and perhaps the single biggest political influence of my life. He is the person I have most tried to emulate in terms of personal integrity and mental rigor.

When Che Guevara was murdered in Bolivia in 1968, Fidel Castro proposed to the Cuban Young Pioneers that they try to “live like Che.” I always thought of Gil as just the sort of U.S. revolutionary that young people should model themselves after—that they should live like Gil.

Even into his late 80s, Gil was still the perennial Young Communist, more imaginative and creative, more distrustful of authority, more resistant to posing or pinning medals on his own chest, than any other radical of whatever age I have come across. Of its many flaws, I always thought that one of the most serious suffered by the leadership of the U.S. Communist Party—one that led to its self-immolation—was that it taught generations of young members to shun the man who was unquestionably the greatest youth leader in its history.

When Gil moved to Ann Arbor to live out his final years in an assisted living facility near Dan, his oldest son, I sorted the papers he left behind in his Chelsea apartment. Among them was a note I found in three separate places, as if Gil really wanted to remember it. It was a portion of a letter from Che to a friend: “The first thing that a revolutionary who is writing history must do,” wrote Che, “is to stick to the truth like a finger in a glove. You did this, but the glove was a boxing glove, so it’s no good.… My advice: re-read the article, take out all that you know is not true, and be wary of all that you are not sure of.”

Gil took Che’s guidance to heart. I suspect it was advice Gil—many year’s Che’s senior—was dishing out before he ever knew of Che. Gil always had difficulty with those of his coworkers who were omniscient. If they never made mistakes, how could they deal with the real problems facing any revolutionary organization? I remember one meeting where Gil said as much: “Look, Comrades, I know how to fry an egg, but I’ll be damned if I know how to unfry one. And that’s the problem we face.”

With little formal education, Gil was a true intellectual, one of the few I have ever known in years of crisscrossing the country’s university campuses and camping out in their libraries. Also left behind in his apartment were some notebooks from his prison years. These contained reams of typed, single-spaced notes and quotations, not only from V. I. Lenin and Georgi Plekhanov, but also from John Donne, Henry George, Immanuel Kant, and Leo Tolstoy. There were others still from and about Michael Harrington, Eric Hobsbawm, and Santiago Carillo. Other notebooks from Leavenworth contained lectures on philosophy, history, and economics that he gave to his fellow prisoners. (Over the years, I met a handful of his ex-prisoner friends, including two reformed bank robbers and a couple of leaders of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party who fired shots into the halls of Congress to bring attention to the colonial status of their island nation.)

Whenever he decided to write a book, Gil approached the subject like a general marshaling all his resources before going into battle. I remember, for example, when he started to write his book about the new-at-the-time crisis facing the labor movement with deindustrialization, the shift from manufacturing to service industries, and the globalization of capital and markets. (This was in 1975, twenty years before the AFL-CIO began to address the crisis.) Gil started by sending out letters to trade unionists he knew from his Young Communist and Communist International days, workers who now led their unions in Italy, Japan, Portugal, Great Britain, and Argentina. He spent several weeks at the Tamiment Library at New York University and the New York Public Library, studying government statistics, reading the available periodicals and books from many points of view—most of them antagonistic to his own—and from many countries. He interviewed scores of labor activists from different movements. And, as with everything Gil wrote, he never criticized a position without giving the reader the best arguments of the person he would then challenge.

Gil was never embittered, despite the abuse he suffered for his beliefs—persecution and imprisonment by his country, insult and denigration by those who called themselves his comrades. I was always struck by his courage, integrity, and devotion to principle. He gave thirteen years of his life on trial, in “the underground,” and in prison for his beliefs, and a year after emerging from prison suffered the loss of his wife.[1] or a man so devoted to his family, this is a story worthy of a telling by Honoré de Balzac or Victor Hugo.

An FBI bulletin published in the early 1950s called on “alert citizens and law enforcement agencies to assist in locating Green” and gave the following description: “Green is a quiet, convincing speaker and is not given to outbursts of emotion except on rare occasions. His appearance is neat and he frequently wears brown suits and flashy ties. He likes to chew gum and smoke cigarettes occasionally.… has worked as a writer, lecturer, electrician and machine shop worker.”

Gil became J. Edgar Hoover’s “most wanted man in America” until voluntarily surrendering to authorities in February 1956. He had three years added to his sentence for contempt of court in jumping bail, but the U.S. Supreme Court later ruled that a sentence for more than one year for contempt was unconstitutional without a jury trial.

I remember when, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern), the Bulgarian Communist Party hosted a week of celebrations of Georgi Dmitrov, the leader of the Comintern who pioneered the United Front Against Fascism. From the United States, they invited Gil, who had actually known Dmitrov. But the U.S. Communist Party did not like this idea, so they prevented him from attending. Instead, the party sent three others who “worked alongside Dmitrov,” although one never left the United States during Dmitrov’s lifetime, and another was a teenager during the Comintern years. They did not realize that the Dmitrov Archives had already recorded several hours of interviews with Gil.

In a January 1994 letter to his friend Milt Wolff—the last commander of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion in Spain—Gil wrote:

You ask about my politics. That’s an understandable question after all that has occurred in the world. Well, I’m still a believer in socialism, although no longer a member of the Communist Party. I find it too stodgy, too set on proving that everything done in the past was correct and that nothing has occurred in the world that requires some reexamination and rethinking. I don’t feel that old that I must freeze my views to what they were yesterday without taking into account compelling new evidence that not everything I believed in yesterday had stood the test of time. And it’s not easy to make such an admission after a near lifetime of affiliation to the CP [Communist Party] as though it were a church.

Gil was hardly a dogmatic religious follower. He was too democratic in nature and spirit. He felt as close to and comradely toward coworkers in other movements who disagreed with him as he did with those who presumably shared his worldview.

For a man of his accomplishments, experiences, and knowledge, he was uncommonly modest. Not only did he not require self-promotion, he disdained it. He was constitutionally incapable of fostering a coterie of boosters and was appalled by those who did.

Gil’s integrity and courage were an embarrassment to many of his comrades because it forced them to face their own lack of them. Many times, he stood up and others wished they had as well. But they had not. Gil was often the recipient of “congratulations in the cloakroom” for having the courage of others’ convictions. There were also complaints after Gil would speak his mind, often the only one, in a meeting. There was the weary “there he goes again,” or the tactical estimate: “Why did he do that? This is the wrong fight at the wrong time.” The right fight being the one waged only when you were certain of victory, or at least knew it would not cost you. And those were the complaints from those who knew Gil was right, not from his opponents.

I often tried to get Gil to piece together how he came to be the way he was. He would usually laugh at such a question, but he would drop a few pieces of information when he was not being pressed. He grew up in Chicago’s Westside Jewish ghetto, the same neighborhood where my father, only a year younger than Gil, was raised. His mother took home work as a seamstress. His dad died when Gil was nine, so he was forced to become a premature adult, with two younger brothers.

Gil could not understand why there was such disparity in Chicago between the wealth of Fields and Wrigley and McCormick, and the poverty of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Roosevelt Road, where he lived. Like many of his generation, he read Jack London and Emile Zola. This was before television and when few had radios. On summer nights, Gil would listen to open-air speakers on Roosevelt Road.

A piano teacher named Leibich, a socialist, loaned Gil books from his personal library and took him to a Young Communist League meeting when he was a teenager. Most of the people at the meeting were in their 20s and spoke a foreign language they called “Marxism.” Someone reported back from a “congress,” but Gil was certain it was not a reference to the legislature in Washington DC. The discussions often went over his head. When the young Communists talked about “orientation,” Gil wondered if this had something to do with Asia. These early lessons may explain why Gil never fell back on the laziness of jargon.

The first demonstration he ever participated in was in support of Augusto Sandino fighting against the U.S. marines’ occupation of Nicaragua. Gil remembered a quarrel in the ranks of the marchers over slogans—some said “Stop the Bloodshed” while others to the left were for more blood.

In 1924—the year of Lenin’s death, Robert Marion La Follette’s Progressive run for president, the founding of the Daily Worker—Gil joined the Communist Party. He was 18. In the party, he met Lillian Gannes, who would become his wife and mother to his three children. (In 1928, the party sent him to Massachusetts to work for the Young Communist League in New Bedford where textile workers, mainly young women, were on strike but had no organization. One of these young women, Helen, would forty years later become Gil’s second wife.)

After the successful San Francisco General Strike of 1934, led by Harry Bridges and the trade union left, a born-again John L. Lewis and a very few like-minded American Federation of Labor (AFL) leaders decided to form the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), organizing the mass-production industries. With no recent experience in organizing, however, Lewis sent work to the Communist Party leaders William Z. Foster and Earl Browder, saying that the infant CIO needed some good young organizers. The party, in response, turned to the Young Communist League. Gil was by now the League’s national organizer and was instrumental in putting together the militants who built what were to become the United Auto Workers, the United Steel Workers, and the CIO.

In 1968, because of his opposition to the Communist Party’s support for the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Gil resigned from the party’s executive body, its Political Bureau, to which he had been elected for thirty years. He was 62 years old and newly unemployed. For many years, Gil had been an advisor and active supporter of various Black caucuses in the labor movement. Jim Haughton, a friend of his who headed up the construction workers’ organization Harlem Fightback, told Gil to go down to the World Trade Center, then under construction, one Monday morning. Hundreds of laborers were about to be hired. So, Gil got in line. Most of the others in line were Black or Latinx and much younger than him. When asked his age, Gil lied by twenty years. They asked what he was doing there. “I told them I used to be a laborer,” he said, “and that I had an ill wife to take care of. They asked to feel my muscles, and after doing so, they were apparently satisfied. So, I was hired and worked thirty to forty stories above the ground.”

Soon after he went to work on the Twin Towers, Gil also took up jogging. He was 68 and I was half that age when he introduced me to this particular form of torture. But we got a lot of visiting done, endlessly round the track and later sitting in the steam room at the McBurney YMCA. (In the winters, Gil would sometimes leave the Y after running a couple of miles, and head up to Central Park for an hour of ice skating.) That is probably where I learned most of what Gil was willing to tell about himself.

Some of my favorite memories were from the times we spent together in Havana and Moscow. There were three different occasions where, by sheer coincidence, we traveled separately but hooked up in these cities. We would spend time walking along the Malecon in Havana, or along Gorki Street where Gil would point out the old Lux Hotel in which Comintern guests were housed. On these walks, Gil would tell “tales out of school” about party leaders that he somehow did not feel free talking about back home. And, as much a spring as he had in his step on the streets of New York, it increased by half in Havana.

After Gil died, his son Ralph told me about a conversation he had just had with Solly Wellman, a friend of Gil’s dating back to the Young Communist League and a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain, who lived in the same retirement community where Gil spent his last months. Solly told Ralph that he would always love Gil because he pointed the way to the defeat of fascism.

In the early 1930s, Gil was head of the Young Communist League, an affiliate of the Young Communist International in Moscow. In August 1934, a number of conservative individuals and mainstream religious and service organizations decided to convene an American Youth Congress. This was in the midst of the Great Depression, when most young people were unemployed. The American Youth Congress was announced as open to all youth organizations. Gil applied for membership on behalf of the Young Communist League and was rejected on the grounds that it would not accept a Communist representative.

Like its parent organization, the Comintern, which coordinated the work of the Communist Parties around the world, the Young Communist International had a delegate stationed in the United States who saw his role as keeping the U.S. Young Communist League on the “right path.” In this case, the right path, it was advised, meant steering clear of the American Youth Congress that was dominated by “bourgeois and petit-bourgeois” organizations. Gil had a different idea of the right path. He met with several of the organizations convening the Youth Congress, as well as with Eleanor Roosevelt who was to be a keynote speaker and was helping guide the preparations for the congress. Gil insisted that the Young Communist League was a bona fide youth organization and should be included. At the congress’s opening session—with about four hundred delegates present—the YMCA representative proposed to the chairwoman that the congress leadership be elected. When she rejected the proposal, there were calls for her to step down. In the debate that ensued, these calls became a majority and she and her entourage left the congress. Nearly all the organizations—and Mrs. Roosevelt—remained. A democratic structure was agreed on, and the Young Communist League was included not only in the American Youth Congress throughout the 1930s, but also in its leadership. I first heard this story before I ever met Gil. It was told to me by James Wechsler in 1962, who was then editor of the (then liberal) New York Post, and who worked with Gil in the American Youth Congress.

A few months after the convening of the American Youth Congress, Gil was summoned to Moscow for a special meeting of the Young Communist International. He had no idea what the meeting’s purpose was, but he knew it must be important. On his arrival, Gil found out that the Soviets had called the meeting to discuss the “deviation” of the U.S. and French Young Communists. The Young Communist International Executive had drafted a resolution condemning the U.S. and French Young Communist Leagues, and demanding that they change their policies. The resolution accused the two of participating in a mixed-class movement that would only dull working-class consciousness. Gil and Raymond Guyot, the French delegate, fought the resolution. Gil had never met Guyot before, but they got along beautifully. Both stood their ground and they became lifelong friends. After some three weeks of debate, Vasili Chemodanov, the Soviet secretary of the Young Communist League, proposed a final meeting; unless Gil and Guyot agreed to the resolution, it would be sent to the U.S. and French Youth Communist Leagues with a demand urging their removal from leadership. Gil and Guyot refused to budge.

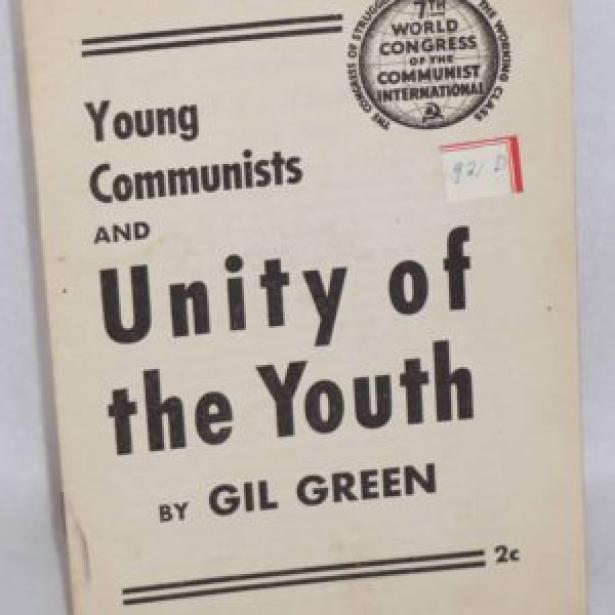

At the concluding debate, Chemodanov stood up and announced that he wished to withdraw the Soviet resolution: “Comrades Green and Guyot are right, and we are wrong.” The background to this change in position was that Dmitrov, who had been on trial for his life in Leipzig, Germany, was freed and came to Moscow, where he assumed his position as Secretary of the Comintern. After his German experiences, Dmitrov argued that the policy of the German Communists had been fundamentally wrong, that it had actually aided fascism’s rise to power, and that it should have been urging unity not only with the German socialists but with all German antifascist forces. Dmitrov began to conduct this fight in the Comintern and in the Soviet Party. When the Young Communist International initiated its resolution against Gil and Guyot, they were unaware of the shift occurring within the Comintern itself. When the Comintern asserted its new position, the Young Communist International withdrew its resolution. Gil did not learn of all this until later, but it was the conclusion of this fight that allowed the Comintern to convene its Seventh World Congress, which called for the United Front Against Fascism. This, in turn, set the stage for the international volunteers in the Spanish Republic and for the antifascist resistance movements in Europe. In the preface to his thesis on the United Front, Dmitrov credited the U.S. and French Young Communist Leagues with pioneering the policy, and he nominated Gil and Guyot as the two youth representatives on the Comintern Executive Committee.

A postscript to this story: Raymond Guyot became a leader of the French resistance and, following the war, was elected a deputy and then a senator in the parliament, and eventually the foreign minister of the French Communist Party.

Another postscript: I was in Moscow at the same time as Gil in 1974. Joseph Stalin had been dead for over twenty years, and the terror no longer existed. All around Moscow, Gil noticed posters announcing a posthumous commemoration of the life of Vasili Chemodanov, the Soviet Young Communist International leader, on his seventy-fifth birthday. The event had already taken place by the time we were there, but Gil learned that the huge hall had been full. Chemodanov’s children and grandchildren were present, and the speeches by those who knew him were of course highly laudatory. A movie was shown of Chemodanov addressing the Sixth Congress of the Young Communist International. But there was one aspect of this emotional event that was odd: not a speaker mentioned how Chemodanov had died. Yet, everyone present knew he had been executed in Stalin’s reign of terror. In fact, this is why they were commemorating his life decades late, but it was still considered inappropriate to mention how his life ended.

The failure to speak truth not only to power but to one’s comrades can be deadly. It was a flaw Gil never exhibited.

The politics Gil fought for in 1934 informed his entire life. For the thirty years following his release from prison, Gil argued against the sectarianism of the Communist Party. I remember him countless times saying, “You can’t have a united front with yourself. A united front means you’ve got to unite with others who in one way or another may disagree with you, who don’t accept you as their leader, but who are ready to join with you on what your objectives are at that particular moment.”

Even in his 60s, for example, Gil attended every single convention of the Students for a Democratic Society. He told an interviewer, “I thought there was something new arising there, something important. And the thing is that a hell of a lot of the Students for a Democratic Society kids were sons and daughters of former party members. It was an interesting phenomenon to see a new generation, whose parents I knew, come forward. The fact is that today there are plenty of working-class youth that go to college. I never finished high school, but my oldest son is a professor at the University of Michigan. Things change. Isn’t that what Marx was all about?”

Left behind in his Chelsea apartment was a note from his granddaughter, Sonya, who had graduated from Brown University and had just moved to New Mexico:

Dear Grandpa, I was so happy to get your letter. It was wonderful to hear that you love me just as much as I love you. I think you are so wonderful and brave. I feel so proud and honored that a man as dedicated and heroic as you is my grandfather. I think of you often, of your struggles and determination, of your will and commitment, of your profound intelligence, and I feel new energy within me. I feel so proud and strong to be your granddaughter. I want you to know how deeply I love you and how completely incredible I think you are. You are such a heroic figure in my life. So much of what I do is inspired by you. I love you, Grandpa, with every bit of my heart.

I don’t suppose many grandparents get this kind of love letter.

Gil, of course, was not my father. But I was always happy to know that I was one of his “kids.”

Afterword: Gil Green and Monthly Review

Given the political differences between Monthly Review’s editors and the U.S. Communist Party’s leadership at the time of the magazine’s founding in 1949, it is no surprise that Gil Green had little association with them. However, Green came to an eightieth birthday celebration for Harry Magdoff in 1993.

It was one of those rare events that marshaled a broad cross-section of what, even then, was called the “old left.” They included old New Dealers, civil libertarians, various affiliated and unaffiliated Marxists and socialists, and even a scattering of liberals. Harry knew most of them from his days as a New Deal activist and the 1948 Henry Wallace campaign, not to mention the New York radical milieu in which he thrived. Green’s presence was mildly surprising, although it should not have been given his party activism and especially his decades-long role as its youth leader.

What did surprise the celebrants was Green’s open affection for those he knew and even his willingness to discuss his past differences with them. In his remarks, he talked about how much of the history of the previous half-century Monthly Review had been right about, and the party had not. He also mentioned things that he thought the party had gotten right and Leo Huberman, Paul Sweezy, and Magdoff had not understood (as he gently put it).

He remembered how, when Monthly Review first appeared, the Communist Party’s National Committee was furious about its criticism of the Soviet Union and directed members to ignore it. So it was that comrades had no idea what Monthly Review was saying until Green quietly, and with his own money, became a charter subscriber and made sure copies were in the party library. As the laughter died down, Gil said he was glad to have helped launch the magazine. While Gil had recently left the Communist Party, his instinct for radical activism—and his playful sense of humor—had not.

—John J. Simon

Notes

1. Along with eleven other top party officials, Gil was indicted in July 1948 under the Smith Act (“conspiracy to teach to advocate the violent overthrow of the government”) and convicted and sentenced to five years imprisonment following a lengthy 1949 trial. Together with three codefendants, Gil became a fugitive from justice following the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the verdict in 1951. They were tasked with leading the Communist Party while the others served out their sentences. Two of the four were captured, but Gil and Henry Winston remained underground.

[Michael Myerson is an author and lifelong activist for civil rights, peace, and labor rights. He lives in the Hudson Valley.]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word