As most of us sat at home during the past year, seeking safety from the pandemic and isolated from each other, we had little to protect us from the onslaught of historic national traumas and anxieties. We watched in horror as over half a million Americans died, millions lost their livelihoods while others had to face the virus at work, an unarmed Black man was slowly murdered by a policeman on camera, and our President encouraged a white rightwing insurrection. All of this is superimposed on the global existential crisis of climate change and the economic abandonment of many places across the country. If years can be ranked by their impact on the mental health and well- being of people, 2020-2021 would easily be near the top of the list.

Even before this terrible year, the nation’s community health and mental health services were in crisis. Funding and access were always limited, and providers struggled to address the “deaths of despair” and ongoing challenges of myriad psychiatric disorders burdening our communities. There was no give in the system before the pandemic. There is even less now.

For working-class Americans, the absence and limitations in mental health services has spawned a culture of self-help and mutual aid outside of formal services, especially for individuals with substance use disorders (see Jennifer Silva’s book We‘re Still Here: Pain and Politics in the Heart of America). Twelve-step programs are the backbone of this culture. Many have found solace in AA or NA meetings, sharing their stories and their aspiration to heal together. When the pandemic hit, they moved online. These meetings carry the seeds of a new approach to care and caring that goes beyond the traditional individual clinical model.

In the past year, we have been inspired by the work of Dr. Adalberto Barreto of Fortaleza, Brazil, who proposes a model of community-based emotional and social support he calls “Solidarity Care.” Unlike the individualized and commodified settler colonialist and neoliberal frameworks of psychopathology and management of mental distress and illness, Solidarity Care emphasizes the human investment of each participant in a network — in their own individual wellness, the wellness of each other, and the wellness of the community. Based on the liberatory pedagogical theories of Paulo Freire and the systems theory of Gregory Bateson, Solidarity Care asserts that each individual has a wealth of experience to share with their community, and in return can rely on their community for contributions of wisdom and perspective. Horizontality of relations is central to this approach. The knowledge or professionals or experts is not deemed more valuable or valid than that of other participants. Within this community therapy framework, a facilitator approaches their work as a member and participant of the community instead of as a separate and external entity.

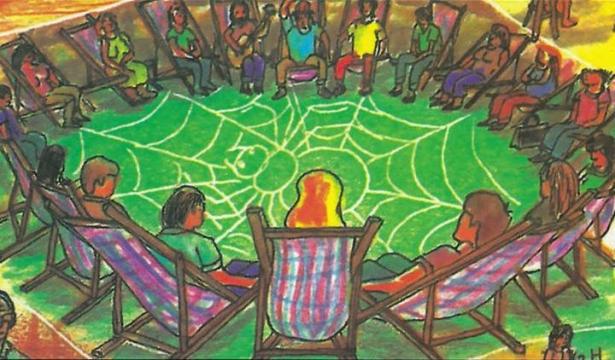

Based on these concepts, Barreto and the residents of the Quatro Varas favela developed an innovative and community-participatory response to their overwhelming needs for mental health care. Terapia Comunitaria Integrativa (Integrative Community Therapy or ICT), is a unique large group open dialogic therapeutic process. It requires only short-term training, can accommodate groups from 10-200 people, and can be performed successfully in an online format. It involves a five-step participatory structure that invites people to share their experiences of suffering and how they have overcome them. The primary benefits are emotional literacy, community building, promoting a sense of “shared suffering,” providing a space of inclusion and diversity, sharing experiences to promote healthy coping strategies, and creating and reinforcing social/support networks. By emphasizing community-building in a shared environment, ICT creates a forum for solidarity, collective healing, and proliferation of resiliency. Participants are encouraged to rely on their internal wisdom, the wisdom of the community, and the wisdom of their ancestors.

ICT does not simply embrace diversity of class, race, religion, gender, and sexuality. It requires it. Diversity of experience enhances the richness and variety of community- sourced solutions to everyday emotional problems. Unlike existing support networks like NA and AA, among others, ICT decentralizes pathology and emphasizes the need for community connection for all people, not just the mentally ill. Within ICT rounds, there is no distinguishing between individuals with a diagnosis and those without. ICT rounds are offered weekly and are open to anyone at any time, with no requirement for future participation.

Finally, a central principle of Barreto’s model is that it is free for all participants. By obtaining funding at the national level, Barreto has moved this model of care away from the fee-for-service medical industrial complex and challenged common reservations regarding scalability due to accessibility and cost.

In the past year, we have begun to bring Integrative Community Therapy to the US, offering the first English language training in this practice. We now have 35 ICT facilitators available nation-wide. In order to create an ICT infrastructure, we must continue to expand our networks and facilitator trainings. While we have found homes within local networks of mutual aid, we face ongoing questions of resources and a hesitation to invest in a non-pathology-based therapeutic model. In order to build a Solidarity Care-based system, we must challenge capitalist models of mental health funding. We must emphasize prevention and people-based primary mental health intervention. This will require community-based service providers to increase their investment in task-sharing and peer support services. Over time, we hope to build a sustainable movement of Solidarity Care-based services to provide safe and reflective spaces for poor and working-class people to develop their internal and interpersonal emotional skills, reinforce the social tissue, and support collective emotional and mental wellbeing through ongoing crises.

Solidarity Care reverses the historic pattern of the West bringing knowledge to the Global South, decolonizing the mental health services system. Models like this have the potential to fill an ever-expanding gap in the social safety net and to restore the social fabric that binds us. By integrating a model of emotional collectivity based in emotional literacy and mutual support, created in one of the most socioeconomically deprived regions of the world, we may find a new way to heal what ails us.

Alice F. Thompson is a fourth-year medical student at the Geisinger Commonwealth Medical School in Scranton, Pennsylvania and Program Director of the Visible Hands Collaborative.

Kenneth S. Thompson is a community and public health psychiatrist in Pittsburgh.

Spread the word