Policymakers Should Expand Child Tax Credit in Year-End Legislation To Fight Child Poverty

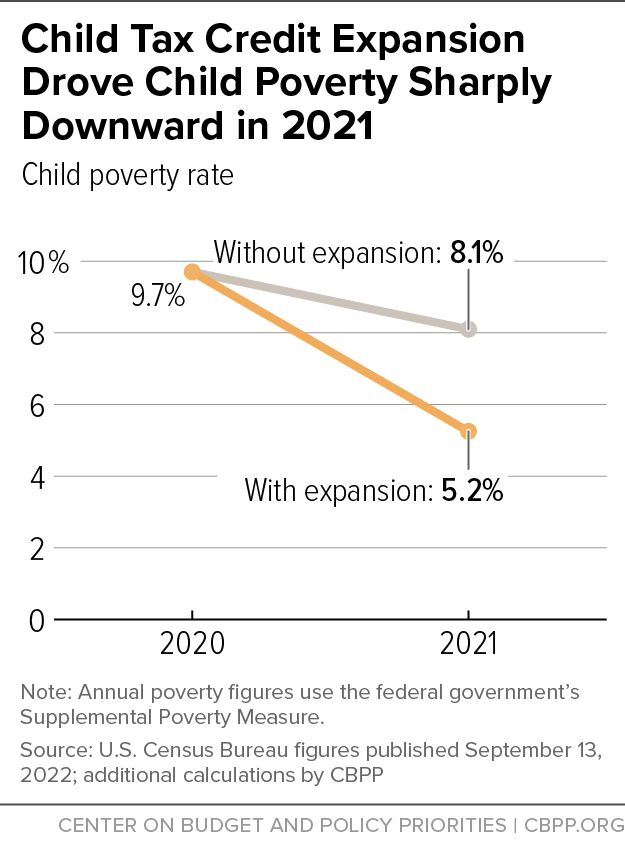

The Child Tax Credit expansion drove child poverty sharply downward in 2021. Combined with other relief efforts, the expansion helped lower child poverty by more than 40 percent between 2020 and 2021, reaching a record low of 5.2 percent, Census Bureau data released last week show. The credit’s expansion expired at the end of last year, but policymakers can renew this successful poverty-fighting policy in year-end bipartisan tax legislation.

There is pressure on Congress from business interests to delay a corporate tax increase; Congress should not consider any business tax breaks without also expanding the Child Tax Credit.

The new Census data are the clearest evidence to date of the expanded Child Tax Credit’s success. Without the expansion (but with other relief measures in place), the child poverty rate would have dropped from 9.7 percent in 2020 to 8.1 percent in 2021, according to the Census Bureau data. But with the American Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit expansion, the rate fell to 5.2 percent, keeping some 2.1 million additional children out of poverty.

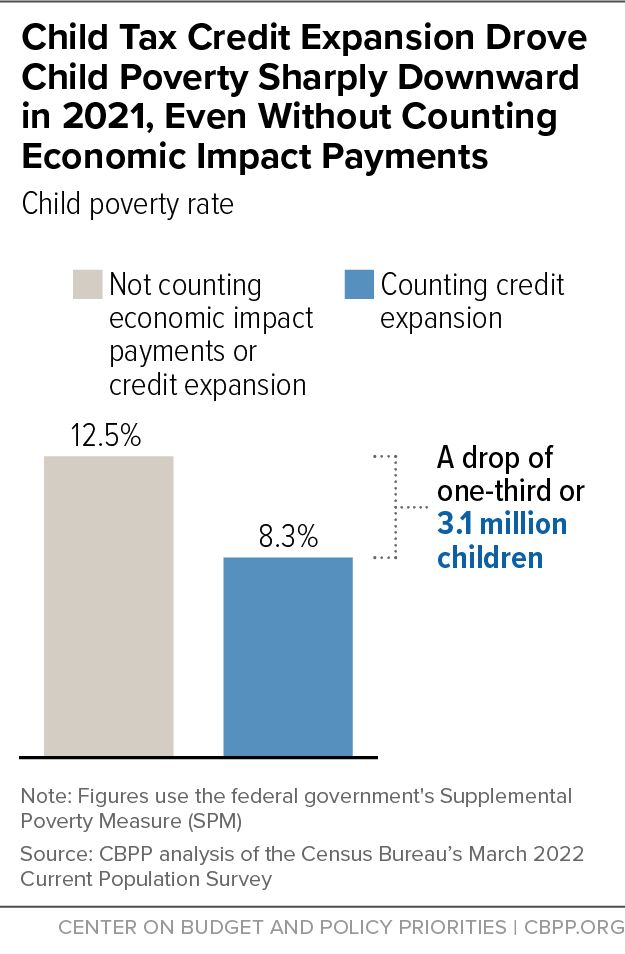

An expansion of the Child Tax Credit, particularly for low-income families who today receive less than the full credit, is even more important going forward because other relief measures — such as economic impact payments — that also boosted families’ incomes during the COVID-19 pandemic have expired.

Congress and the Biden Administration now face a stark choice: whether to expand the Child Tax Credit or allow all of the gains against child poverty made over the last two years to evaporate, with millions of children needlessly falling back below the poverty line. Research has found that additional income from policies such as the Child Tax Credit improve the health, educational achievement, future earnings, and lifelong prospects of children in low-income families. The new Census data underscore that this policy success — if policymakers act — could change the future for millions of children in our country.

Year-End Opportunity for Bipartisan Progress

Year-end legislation will need to be bipartisan, and there is bipartisan support for expanding the Child Tax Credit.

Democratic champions have noted the strong poverty impacts of the expansion and have renewed their commitment to expand the credit, which has also been a top priority of the Biden Administration. And some Republicans, who expanded the Child Tax Credit in 2017 in their tax cut bill as well as in the 2001 tax cut bill, have also shown signs of interest in expanding the credit. Senator Mitt Romney recently proposed an expansion of the Child Tax Credit and Senator Marco Rubio, who with Senator Mike Lee was central to the inclusion of an expansion in the 2017 tax law, also released a Child Tax Credit expansion plan with Representative Ashley Hinson.

There is a possible path for bipartisan year-end legislation. As they have in prior bills this year, corporate lobbyists are pressing Congress to delay a tax increase enacted in the Trump 2017 tax law related to the tax treatment of research and experimentation (R&E) expenses before the end of the year. In 2017, to reduce the cost of cutting the corporate tax rate to 21 percent, congressional Republicans required businesses, beginning in 2022, to deduct the costs of their R&E investments (or “amortize” them) over five years instead of deducting the full costs immediately. At the time, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that this would raise $120 billion over ten years.

If Congress now wants to reverse this policy — and return the tax treatment of R&E investments to immediate expensing — then it should simultaneously reverse a corresponding amount of the deep cut in the corporate tax rate. But that is unlikely to happen in year-end bipartisan legislation. Meanwhile, corporate interests are expected to continue to press aggressively for a delay of the R&E provision, which would mean yet another corporate tax cut.

Policymakers should not put corporate interests ahead of the interests of children. That means that this corporate tax cut related to R&E expenses — or any other business tax cut — should not move without an expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Some policymakers have already made clear that they do not support moving ahead with a corporate tax break without an expansion in the Child Tax Credit. For example, in response to the Census report, Senators Bennet, Brown, and Booker and Representatives DeLauro, DelBene, and Torres said that Congress should not enact corporate tax provisions in year-end legislation without also expanding the Child Tax Credit.

A Record Reduction in Child Poverty

The child poverty rate fell to a record low in 2021, the Census Bureau announced on September 13. The rate fell by 4.5 percentage points, from 9.7 percent to 5.2 percent — the largest year-to-year drop ever. The rate is a record low not only in Census figures that start in 2009 but in analyses of historical data assembled by Columbia University back to 1967.

In 2021, two policies in particular drove down child poverty — the expanded Child Tax Credit and the third round of economic impact payments. In the last two recessions, the federal government used broad based stimulus payments to help households weather the economic downturn and to boost demand to help the economy recover.

If the Child Tax Credit had not been expanded (but with the economic impact payments and other policies in place), the child poverty rate would have stood at 8.1 percent. With the Child Tax Credit expansion also in place, the child poverty rate fell to 5.2 percent. (See Figure 1.)

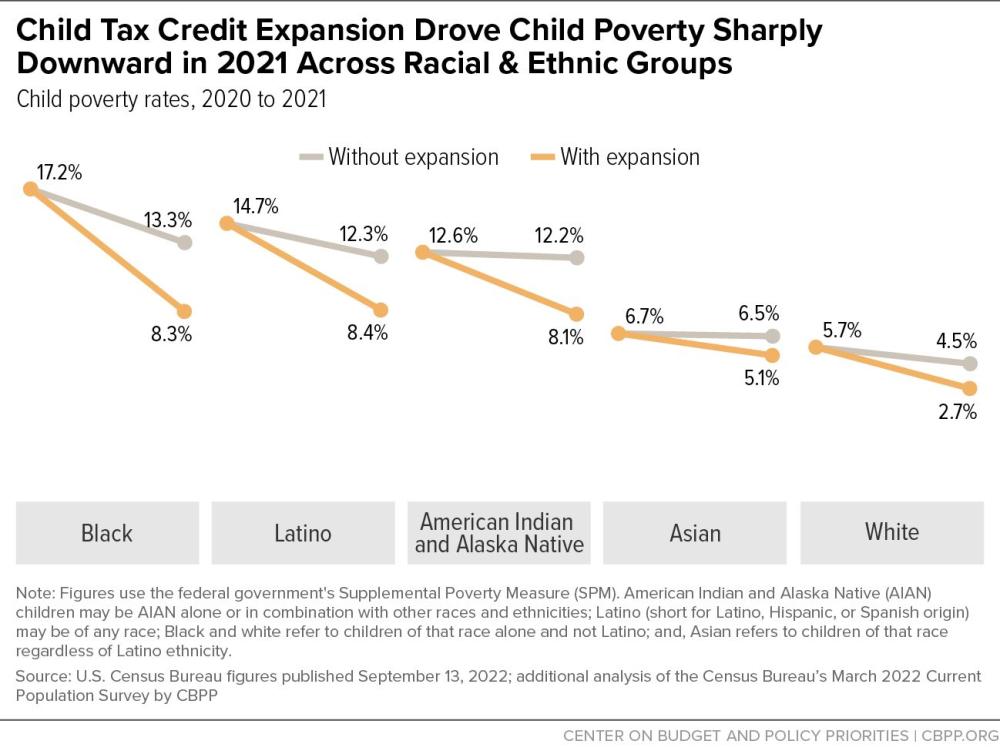

Without the Child Tax Credit expansion, some 2.1 million more children would have been in poverty in 2021 — including 752,000 Latino children, 649,000 white children, 524,000 Black children, 89,000 American Indian and Alaska Native children, and 56,000 Asian children, based on Census estimates of families’ taxes. Moreover, the Child Tax Credit expansion improved conditions for children of all races and ethnicities and narrowed differences in poverty rates between them. (See Figure 2.)

Since economic impact payments are not being considered as an ongoing policy, another way to look at the data is to consider what the child poverty rate would have been in 2021 if there were no economic impact payments and no expansion in the Child Tax Credit. Without both of these policies, child poverty would have stood at 12.5 percent. Adding in the expanded Child Tax Credit (without the economic impact payments) would have reduced the number of children in poverty by 3.1 million and reduced the child poverty rate to 8.3 percent, itself a historic low, a reduction of one-third. (See Figure 3.)

How the Child Tax Credit Expansion Helped Families

The Rescue Act made the full Child Tax Credit available to children in families with low earnings or that lack earnings in a year, and it increased the credit’s maximum amount to $3,000 per child and $3,600 for children under age 6. It also extended the credit to 17-year-olds. The increase in the maximum amount began to phase out for heads of households making $112,500 and married couples making $150,000.

For example, a single mother of a toddler and a second grader, who earns $14,000 a year providing in-home care to older people (with work hours that fluctuate significantly from month to month), received a Child Tax Credit of $1,725 in 2020. Under the Rescue Plan for 2021, this family received a $3,600 credit for the toddler and $3,000 for the second grader, for a total of $6,600 delivered in stabilizing $550 monthly amounts during the second half of 2021. That was a gain of $4,875 relative to 2020. Millions of such families benefitted from the Rescue Plan’s expansion.

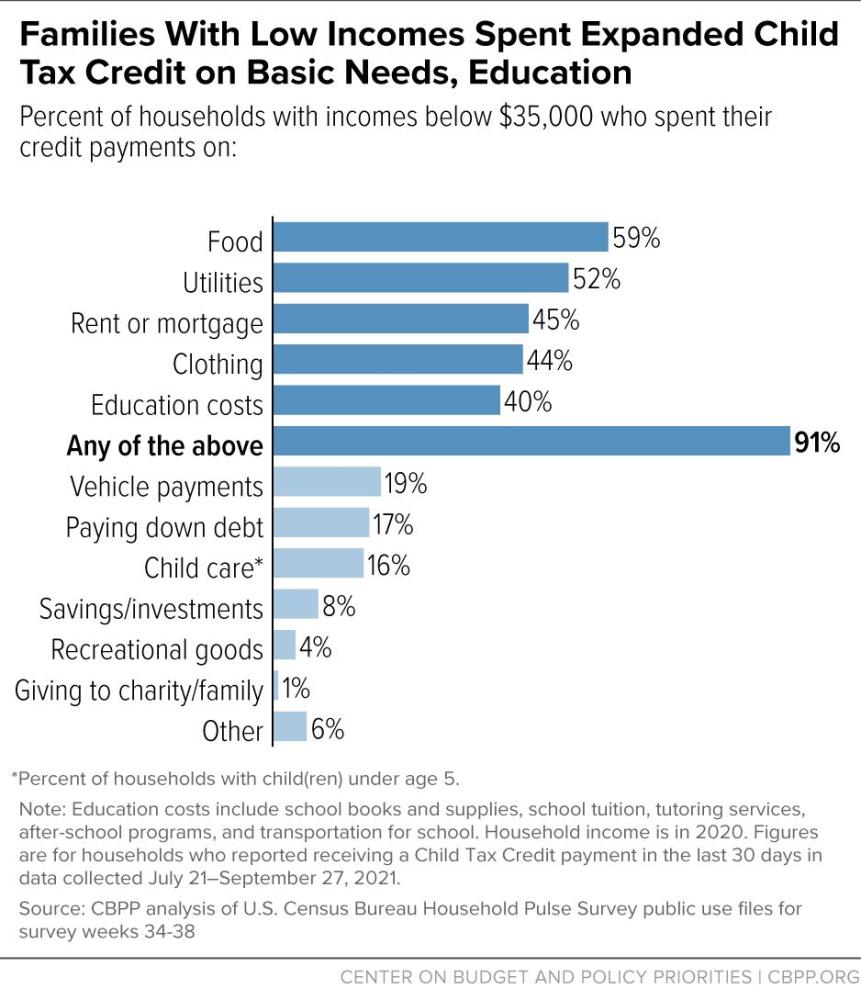

The Census Bureau provided real-time data on how parents were spending these monthly deposits and what this meant for children. Food topped the list of how families with low incomes used this money. (See Figure 4.)

As a result, for example, in the month and a half after the federal government began issuing monthly payments of the expanded Child Tax Credit, the share of adults living with children reporting that their family didn’t have enough to eat in the past seven days fell significantly. The prevalence of food insecurity among households with children fell substantially, from 14.8 percent in 2020 to 12.5 percent in 2021, and nearly 2.5 million fewer children lived in households that experienced food insecurity. The share of households where children were food insecure reached a two-decade low in 2019 (6.5 percent of households with children) but increased significantly early in the pandemic, rising to 7.6 percent of households with children in 2020. However, this measure returned to the pre-pandemic low in 2021 (6.2 percent).

For children, poverty can mean unstable housing, frequent moves, inadequate nutrition, and high levels of family stress, and other problems. These in turn have been linked with lower reading and math scores, more emotional and behavioral problems, fewer years of completed education, lower earnings, higher likelihood of being arrested, and poorer health in adulthood, a 2019 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report on reducing child poverty found. “he weight of the causal evidence indicates that income poverty itself causes negative child outcomes, especially when it begins in early childhood and/or persists throughout a large share of a child’s life,” the report concluded.

By contrast, boosting children’s inadequate family incomes with an expanded Child Tax Credit and reducing poverty over the long term would mean better lifetime health, improved educational attainment, and higher earnings and better economic circumstances as adults.

Contrary to predictions that the credit would trigger major declines in parental employment, the number of working-age adults working a large share of the year rose by similar amounts for those with and without children. The number of adults aged 18 to 64 who worked full time, year-round rose by 10 million in 2021 — the largest such increase since at least the 1980s — Census reported, and analysis of the survey data indicates that the rise in the share working full time, year-round was about as large among adults in families with children under 18 (up 5.8 percentage points) as without children (up 5.2 percentage points). Similarly, the share working the equivalent of at least half the year (1,000 hours) rose as much among those with children as those without children.Although most parents received the Child Tax Credit payments starting in July, there was no obvious sign of a relative decline in either of these measures of parents’ employment.

Without action to expand the Child Tax Credit (and with the expiration of various relief measures), child poverty is likely to return to about the same level as it was pre-pandemic — pushing millions of children back into poverty. This presents Congress and the Biden Administration with a stark policy choice to make this year — they can take steps to expand the Child Tax Credit and make sustained progress in reducing poverty, or they can see all of the gains made in recent years evaporate.

End Notes

Kalee Burns, Liana Fox, and Danielle Wilson, “Expansions to Child Tax Credit Contributed to 46% Decline in Child Poverty Since 2020,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 13, 2022, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/record-drop-in-child-poverty.html.

Senators Bennet, Brown, Booker, DeLauro, DelBene, and Torres, “Bennet, Brown, Booker, DeLauro, DelBene, Torres Statement on Extending the Expanded Child Tax Credit Before Year End,” September 13, 2022, https://www.bennet.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2022/9/bennet-brown-booker-delauro-delbene-torres-statement-on-extending-the-expanded-child-tax-credit-before-year-end.

Chuck Marr et al., “Romney Child Tax Credit Proposal Is Step Forward But Falls Short, Targets Low-Income Families to Pay for It,” CBPP, July 6, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/romney-child-tax-credit-proposal-is-step-forward-but-falls-short-targets-low; Senator Mitt Romney, “Romney, Burr, Daines Announce Family Security Act 2.0,” June 15, 2022, https://www.romney.senate.gov/romney-burr-daines-announce-family-security-act-2-0/.

Senator Marco Rubio, “Rubio Introduces Pro-family Plan for a ‘Post-Roe’ America,” September 15, 2022, https://www.rubio.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?id=194A5B28-01BB-478C-83BD-6D5923D43DB9.

Senators Bennet, Brown, Booker, DeLauro, DelBene, and Torres.

American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children may be AIAN alone or in combination with other races and ethnicities; Latino (short for Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish origin) may be of any race; Black refers to children of that race alone and not Latino; and, Asian refers to children of that race regardless of Latino ethnicity. The figure for Black children rises to 600,000 when Black children identified as Latino are included. Burns, Fox and Wilson op. cit. for estimates of children identified as Latino, white, Asian, and Black (including those identified as Latino) and CBPP analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2022 Current Population Survey for estimates of children identified as non-Latino Black and American Indian and Alaska Native.

Daniel J. Perez-Lopez, “Household Pulse Survey Collected Responses Just Before and Just After the Arrival of the First CTC Checks,” Census Bureau, August 11, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/economic-hardship-declined-in-households-with-children-as-child-tax-credit-payments-arrived.html; Zachary Parolin et al., “The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material Hardship,” NBER Working Paper No. 29285, September 2021, www.nber.org/papers/w29285; Paul R. Shafer et al., “Association of the Implementation of Child Tax Credit Advance Payments With Food Insufficiency in US Households,” JAMA Network Open, Vol. 5, No. 1, January 13, 2022, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2788110.

Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2021,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, September 2022, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/104656/err-309.pdf.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, National Academies Press, 2019.

CBPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s March Current Population Survey data. For further discussion, see https://twitter.com/TrisiDanilo/status/1572269274605166594.

Chuck Marr is the Vice President for Federal Tax Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. From 1999 through 2004, he was Economic Policy Advisor to Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle and Senior Advisor for Budget Policy at the National Economic Council from 1997 through 1999 during the second term of President Clinton. Tax policy was a key area of responsibility in both these positions. In addition, earlier in his career he worked on the staffs of the Senate’s Budget and Banking committees. Prior to joining the Center in March of 2009, he was a senior political strategist in the Washington Research Group of Lehman Brothers and Barclays Capital, where he analyzed the impact of public policy on financial markets. He has also taught as an adjunct professor at Georgetown University.

Marr has a BA in Economics from the University of Rochester and an MBA in Finance from Columbia Business School.

Danilo Trisi is the Director of Poverty and Inequality Research. His work primarily focuses on trends in poverty, deep poverty, income inequality, the labor market, and the effectiveness of economic security programs.

Since joining the Center in 2007, Trisi has played a vital role in expanding the Center’s data analysis capacity. He has deep expertise in analyzing a variety of national survey data, administrative record systems, and micro-simulation data concerning economic well-being, racial and other disparities, and the influence of tax and transfer policies. He provides support to many of the Center’s cross-cutting research projects such as the design of policies to help eligible families more easily access medical and nutrition assistance and assessing the impact of public policies on immigrants and other vulnerable populations.

Prior to joining the Center, Trisi worked as a Program Associate at USAction, providing research and field support for their federal budget and tax campaigns. He was also a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education.

Trisi holds a Ph.D. from the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy, a master’s degree in Latin American Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and a bachelor’s degree from Pomona College.

You can follow him on Twitter @TrisiDanilo.

Arloc Sherman is Vice President for Data Analysis and Research at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Sherman’s work focuses on family income trends, income support policies, and the causes and consequences of poverty. He has written extensively about the effectiveness of government poverty-reduction policies, the influence of economic security programs on children’s healthy development, the depth of poverty, tax policy for low-income families, welfare reform, economic inequality, material hardship, parental employment, and the special challenges affecting rural areas.

He is a member of the Census Bureau National Advisory Committee on Racial, Ethnic, and Other Populations and was a member of the National Academy of Sciences Committee on National Statistics Panel to Review and Evaluate the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation's Content and Design. Prior to joining the Center in 2004, Sherman worked for 14 years at the Children’s Defense Fund and was previously at the Center for Law and Social Policy. His book Wasting America’s Future was nominated for the 1994 Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

Kris Cox is Deputy Director of Federal Tax Policy with the Center's Federal Fiscal Policy division. She previously provided management and research oversight to country teams across West, East, and Southern Africa as a Regional Director for Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA). Prior to that she opened IPA's office in Rwanda, where she spent over three years managing randomized controlled trials to evaluate the impact of social programs designed to assist the global poor across a variety of sectors, working closely with policymakers and non-governmental partners. Cox worked at the Center from 2007 to 2010 as a Research Associate with the Federal Fiscal Policy division. Prior to that she taught civic literacy skills to low-income parents as a Public Allies AmeriCorps member at Imagine Chicago. She holds a Master in Public Policy degree from the Harvard Kennedy School and a Bachelor of Arts in Mathematics and History from the University of Virginia.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Who We Are

We are a nonpartisan research and policy institute that advances federal and state policies to help build a nation where everyone — regardless of income, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, ZIP code, immigration status, or disability status — has the resources they need to thrive and share in the nation’s prosperity.

What We Do

We combine rigorous research and analysis, strategic communications, and effective advocacy to shape debates and affect policy, both nationally and in states.

We work closely with a broad set of national, state, and community organizations to design and advance policies that promote economic justice; improve health; broaden opportunity in areas like housing, health care, employment, and education; and lower structural barriers for people of color and others in communities that continue to face systemic barriers to opportunity.

We promote federal and state policies that will build a stronger, more equitable nation and fair tax policies that can support these gains over the long term. We also show the harmful impacts of policies and proposals that would deepen poverty, widen disparities, and worsen health outcomes.

We work on policy implementation at the federal, state, and local levels to maximize the positive impact of policies and bring the lessons learned on the ground back to the policymaking process in Washington and state capitals.

Our work — rooted in sound research and original data analysis, informed by our extensive knowledge of policy and how programs operate on the ground, and strengthened by our collaboration with a broad range of partners — is trusted by a wide range of researchers, policymakers, and media.

Our History

In 1981, Robert Greenstein founded the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) to analyze federal budget priorities, with a particular focus on how budget choices affect people with low incomes. In our early years, the Center focused on federal budget and tax issues, nutrition programs, and income assistance. Our work has broadened considerably over time and now includes research and advocacy on a wide range of issues including health care, housing, and the economic and health security of immigrants.

Recognizing the critical role that state policy plays in economic and health security, we began extensive work on state-level policies in the 1990s. We founded — and continue to coordinate and foster — the State Priorities Partnership, a network of high-impact policy and advocacy organizations that now stretches across more than 40 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. Sharing with the Center a strong emphasis on designing and promoting policies that foster economic, health, and racial justice, these independent nonprofit organizations collaborate with a host of partners in their states to shape policy debates.

Our Impact

Over the last four decades, the Center has played a significant role, in collaboration with partners around the country, in major advances in economic and health security policies nationally and in states.

We have helped protect and expand health coverage for millions of people, extend and expand refundable tax credits that lift millions above the poverty line, and strengthen nutrition, housing assistance, and income support to help people afford basic needs. These policies improve people’s near-term well-being; promote equity across lines of race, ethnicity, immigration status, and gender; and have long-run payoffs for them and the country as a whole.

When the Center was founded in 1981, economic security programs lifted just 20 percent of people who would otherwise be poor above the poverty line. Prior to the pandemic in 2019, that figure had more than doubled to 46 percent; economic security programs lifted 34 million people above the poverty line that year, reducing the poverty rate from 22.8 percent to 12.2 percent. In 2020, during the pandemic and its economic fallout, economic security programs and temporary COVID-19 relief measures increased the number of people kept above the poverty line substantially to 53 million. Advances in economic security programs have reduced poverty across racial and ethnic groups while also narrowing disparities significantly, though large gaps remain.

Similarly, expansions we helped to drive in Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) subsidized coverage through federal and state marketplaces have changed the landscape of health coverage. In the early 1980s, Medicaid was small, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) didn’t exist, and most people in low-paid jobs had no access to affordable coverage unless their employer provided it. Prior to the pandemic, some 81 million people — 25 percent of the U.S. population — received coverage through Medicaid, CHIP, or the ACA marketplaces.

State Priorities Partnership groups have secured important policy advances across the country. Among other victories, over the past several years, Partnership groups have helped to raise or protect roughly $40 billion in state revenue to support a range of investments, such as in education, health care, and infrastructure; have contributed to adoption of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in a number of states; and have worked toward new or expanded state refundable tax credits in more than a dozen states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia, expanding state earned income tax credits by more than $1 billion and increasing their reach to millions more households.

The Center is also helping to build the next generation of state policy leaders through the State Policy Fellowship program. This program brings dynamic emerging leaders who know the challenges faced by communities of color, LGBTQ people, immigrants, tribal communities, and low-income families to Partnership groups and the Center by offering them two-year paid positions as policy analysts, as well as a host of other supports, training, and networking opportunities.

Spread the word