The Chicago Board of Education’s vote on Wednesday to convert three public elementary schools into “turnaround schools” run by the non-profit Academy for Urban School Leadership (AUSL) was no surprise to most parents and teachers.

The board has consistently voted to close schools or turn them over to private management—laying off most of the staff in the process—despite overwhelming opposition, anxiety and outrage expressed in heartfelt testimony by parents, teachers, students and elected officials at scores of public meetings.

While the concept of turnaround schools was first instituted under former Mayor Richard M. Daley, critics see the use of turnarounds as a signature of Mayor Rahm Emanuel and his aggressive privatization agenda. Parents and experts framed the recent vote as part of a larger trend wherein Emanuel, who appoints the school board, has disregarded public opinion to push through his privatization plans. The mayor has met more resistance from the teachers union and parents, however, than he may have expected. He was widely seen as “losing” the standoff with the teachers union that culminated in their seven-day strike in 2012 and a new contract for the teachers. Schools CEO Jean-Claude Brizard, a prominent proponent of charter schools and privatization, resigned in the wake of the strike.

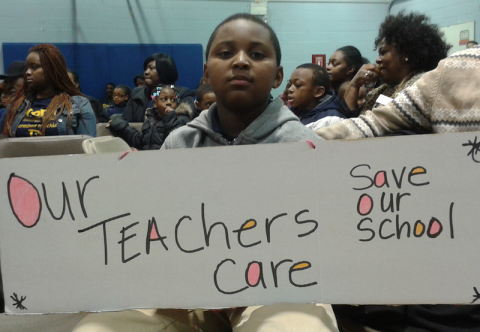

Even before the April 23 meeting, the board members should have been well aware that public sentiment stood firmly against “turning around” McNair Elementary, Gresham Elementary and Dvorak Technology Academy, all of which are in predominantly African-American neighborhoods. During public meetings at each school in recent weeks, community members berated AUSL officials, calling them “traitors” to the Black community, and pleaded with them to save the jobs of the principals and teachers. The tenor of these meetings echoed scores of hearings held about the plan to close almost 50 public schools in 2013. It was evident this month that to many parents and students, being “turned around” is nearly equivalent to being closed. While the school remains open after a turnaround, students and parents said that without the teachers and staff that they have grown to know and love, the school isn’t the same.

Parents reiterated the same points at the April 23 meeting, but all five of the school board members present voted in favor of the turnaround proposals. (The board has seven members total, but can hold votes with five.)

AUSL already runs 29 Chicago schools with more than 17,000 students. Now it will take over the three elementary schools in the fall, and 147 employees, including 76 teachers, will lose their jobs.

The school district says that the teachers will be allowed to reapply for their jobs and that about 60 percent of teachers laid off from turnaround schools receive positions somewhere in the Chicago public-school system by the next fall. But these jobs can be anywhere in the city, offering little consolation to parents who emphasized how teachers at neighborhood schools are like family to the students, especially since multiple generations have attended the same schools and even had the same teachers.

“There’s not a day that goes by my kids don’t want to go to school,” said Dvorak parent Candace Stigler at the board meeting on April 23, noting that AUSL’s promises of trips to Dave & Buster’s and Medieval Times restaurants are meaningless to her. “It takes a village to raise a child. … Dvorak is our village.”

Gresham parent Anthony Jackson addressed Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett directly. “Let me first tell you all, Ms. Byrd-Bennett,” said Jackson, wearing an I Love Gresham T-shirt, “the parents at Gresham, we took a vote about whether we want AUSL to come into our school or not. … Overwhelmingly 188-4, we do not want AUSL at our school. Secondly, no one consulted with the parents in the community. You do not understand an impoverished community, first of all—you don’t come from that. Your children don’t go there. To blame the teachers, it’s not right!”

As is often the case with schools that are closed, privatized or subject to sweeping reforms, all three schools are in poor neighborhoods—Dvorak and McNair on Chicago’s West Side and Gresham on the South Side. All three have had consistently low scores on standardized tests and have been placed on probation by the district for between six and 14 years. But parents say that teachers at the schools are dedicated, caring and skillful, and shouldn’t be punished for problems that stem from a lack of resources.

Gresham principal Dr. Diedrus Brown—herself a graduate of Chicago Public Schools—noted at the board meeting that Gresham’s test scores have fluctuated according to how much funding the school has received. Gresham’s budget was cut in 2013, and the school was forced to lay off three teachers and three staffers.

“I saw what happened at the school when we were given extra money,” Brown said. “Then you destabilized our school for the past two years by taking money away. … I lost programs, I lost positions. … What AUSL gets in terms of finances—give some of that back to the neighborhood schools. It’s Chicago Public Schools, not Chicago Private Schools.”

Brown and others say it is unfair that turnaround schools get $300,000 in startup funding, plus, for five years, $420 per student more than other CPS schools receive.

Dion Stone, a parent and Local School Council member at McNair, had prepared remarks for the April 23 board meeting. But after hearing glowing testimony from several principals and parents at other AUSL schools, Stone scuttled his planned statement and spoke spontaneously.

“I thought they’ve got a lot of nerve,” he said of the AUSL representatives. “Talking about what they can offer, the programs they have and their test scores. With their big budget they can offer all of that,” he said—referring to soccer and cheerleading teams, excursions to Dave & Buster’s restaurant and other perks trumpeted by AUSL representatives.

“Our teachers don’t have working computers. They have to bring their own laptops to school, buy their own printer paper,” Stone continued. “And even with the diminished budget we have, our test scores have been rising, in some cases competing, in some cases beating AUSL.”

The Chicago Teachers Union has long charged that the city has been deliberately starving neighborhood schools like Gresham, Dvorak and McNair of resources, in order to help justify either closing them or turning them over to private management. In this year’s budget, schools across Chicago saw funding cuts of 10 to 25 percent.

After the vote, CTU president Karen Lewis released a statement that the schools had been “set up for failure," which read in part:

Today’s hostile takeover of three of our neighborhood school communities by the mayor’s handpicked Board of Education makes it quite clear that there is a war on older, African-American teachers and administrators, as well as the school communities in which they serve. … This dubious, corporate reform model has proven to do little but take over schools discredited by CPS and then, after receiving millions of dollars in support, take credit for the sudden but short-lived academic success among students.

Denise Little—the Chief Officer of Networks for Chicago Public Schools, part of a five-person cabinet the school district created in late 2012—would likely disagree. She began the April 23 meeting by reciting statistics about AUSL school performance, including that AUSL schools improve more on standardized tests than the average improvement rate.

“Students at AUSL schools have the opportunity to learn in safe, supportive environments,” Little said. “AUSL has had a profound impact on academic performance and school culture.”

But critics point to uneven performance in the turnaround schools managed by AUSL. While test scores in these schools increased during the first years under the group’s management, they stagnated soon afterwards. As of last year, 11 of the 12 schools taken over by AUSL between 2006 and 2010 had composite ISAT scores below the CPS district-wide average, as Curtis Black reported for the Community Media Workshop. Two AUSL-operated schools in the low-income area of North Lawndale have actually seen drops in their composite test scores of late. And while 33 Chicago elementary schools with student poverty rates above 95 percent achieved above-average ISAT reading scores in 2012, none of them were AUSL schools, according to a study by Don Moore of Designs for Change.

Moreover, Lewis and others at the meeting said that the “culture” at AUSL schools is often unstable and confusing for students, since they are dealing with new teachers and staff and a new principal. After AUSL takes over a school it hires replacement teachers and staff—who are members of the Chicago Teachers Union, but union leaders still describe the practice as undercutting union teachers’ rights and protections—and the new teachers are more likely than usual to leave themselves within two or three years. A January report by Catalyst Chicago magazine said that the turnover had led to “what students and staff described as a chaotic environment.”

Frustration and anger was palpable as parents and students left the meeting. Security officers surrounded one man who called out, “Denise Little, you can expect a visit, we’re going to your house, baby!”

Though Mayor Emanuel wasn’t at the board meeting, he was very present in the minds of parents and other critics—including several who invoked the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, the elite private institution Emanuel’s kids attend.

“You’re taking the money, you’re bleeding the school of resources, then you expect [the teachers] to be magicians and produce top-of-the-line children competing with Lab schools and all that,” said Jackson, growing teary as he talked about how Gresham teachers helped his son transition out of special education. “Please, board members, do not turn Gresham around. Give us the funds and I know the teachers will show you all they are capable of producing schools like the Lab School.”

This report was made possible by a generous grant from the Voqal Fund.

Portside is proud to feature content from In These Times, a publication dedicated to covering progressive politics, labor and activism. To get more news and provocative analysis from In These Times, sign up for a free weekly e-newsletter or subscribe to the magazine at a special low rate.

Spread the word