One of the most surprising results to come out of a survey released this week by the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) was in response to a question buried in the “general health” section.

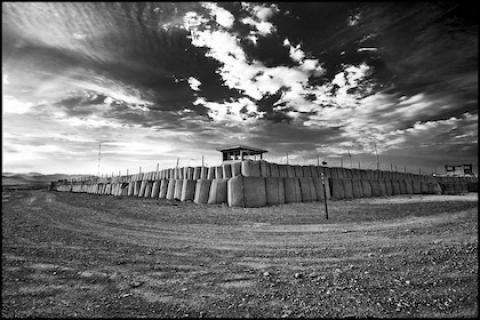

It was a question about exposure to “burn pits,” open-air fields where the US military burned water bottles and plastic-foam cups, as well as human and medical waste (which sometimes included hypodermic needles and, some troops report, amputated limbs).

The waste was generally lit on fire with jet fuel, and the flames often reached two or three stories high. In IAVA’s survey of some 2,000 US service members who had combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, three-quarters reported being exposed to burn pits while deployed. Of those exposed to burn pits, more than half – 54 percent – say that they “feel they have symptoms associated with that exposure.”

The effect of burn pits on the health of US troops is “arguably the iceberg of Iraq and Afghanistan public health,” argues Phil Carter, director of the Military, Veterans, and Society Program at the Center for a New American Security in Washington.It is a public health concern that the Department of Veterans Affairs has been grappling with for some time, with an approach that in many respects has mirrored the VA’s approach to Agent Orange victims in the Vietnam War, Mr. Carter says.

Some veterans have complained that the burn pits released carcinogens and other particulates into the air that led to respiratory conditions and, in some cases, leukemia.

In 2009, the Army released a study of air quality in US war zones that concluded that while levels of particulate matter near the burn pits were “extraordinarily high” by American standards, there were no “statistically significant” associations between the pits and cardiovascular or respiratory conditions.

Lawmakers asked the Government Accountability Office to review the Army’s findings for “significant methodological problems.” The GAO found, among other things, that the air-quality samples were collected during the rainy season, when particulate matter is less prevalent.

The US military has replaced most burn pits with incinerators, but in 2014 the special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction found that prohibited material – which, through a 2009 law, includes munitions, asbestos, tires, mercury, batteries, and aerosol cans – was still being burned in open-air pits from 2011 to 2013.

The VA has established an “Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry” for troops, though the VA website says, “at this time, research does not show evidence of long-term health problems.”

Even so, the VA says, “veterans who were closer to burn pit smoke or exposed for longer periods may be at greater risk,” and adds that “health effects depend on a number of other factors, such as the kind of waste being burned and wind direction.”

The burn pit registry “will make it easier to monitor health and ensure they won’t have to fight for the care they deserve if they need it,” Rep. Carol Shea-Porter (D) of New Hampshire told the Monitor.

Even so, lawmakers have vowed to follow up on the IAVA report. “Some service members are still being exposed in Afghanistan,” says Representative Shea-Porter. “I will continue working until none of our troops are unnecessarily exposed to toxic smoke.”

[Anna Mulrine is a staff writer for the Christian Science Monitor]

Spread the word