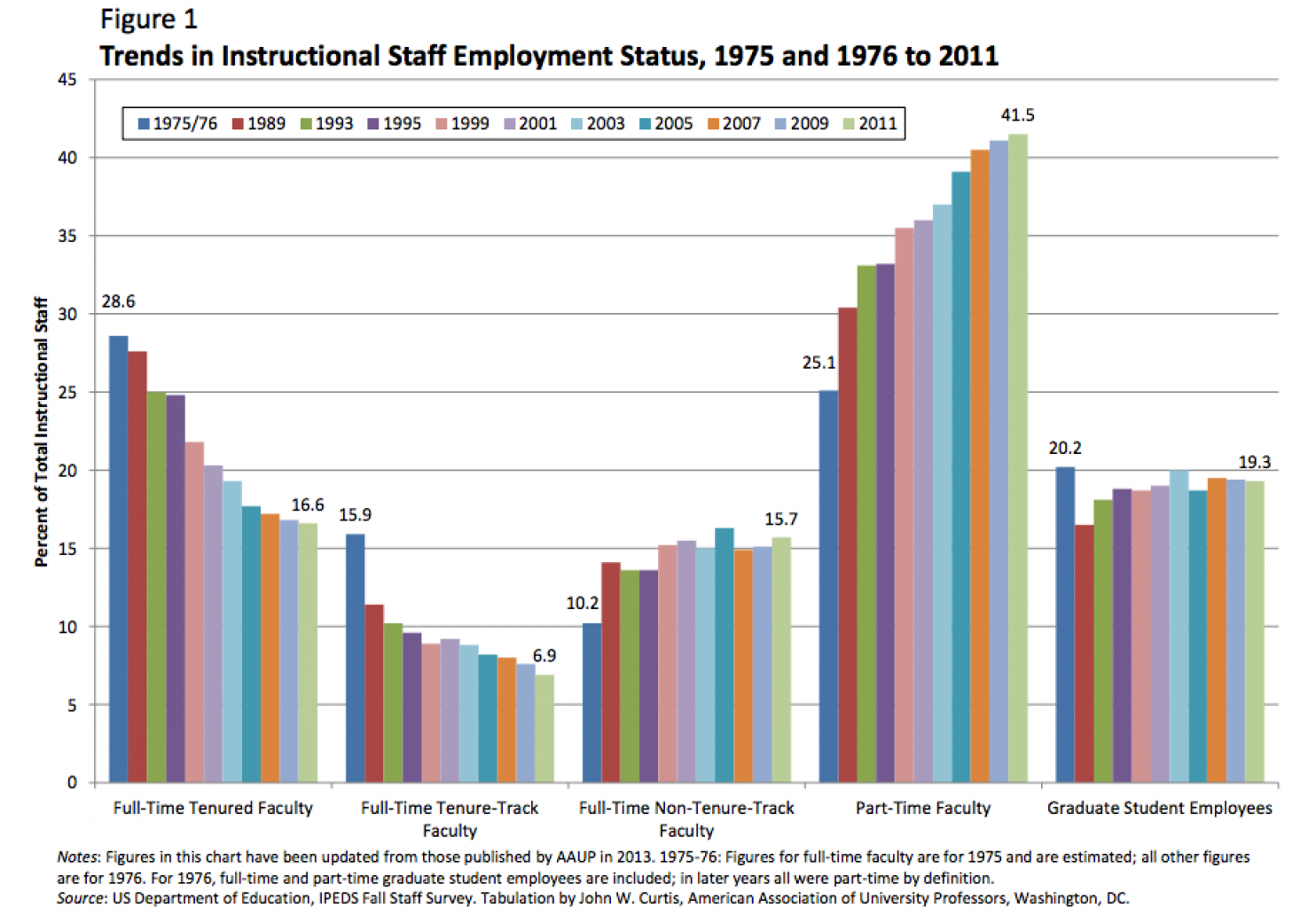

It's been true for a long time now that academia - or at least the part of it that teaches students - relies heavily on the labor of adjunct faculty. As the number of tenured professors has fallen, universities have filled more than half of their schedules with teachers who work on contract. And no wonder: They'll work for less than half what a full-time professor makes, at a median wage of just $2,700 per course, with scant benefits, if any.

Now, a union that's been rapidly organizing adjuncts around the country thinks that number should quintuple. Last night, on a conference call with organizers across the country, the SEIU decided to extend the franchise with a similar aspirational benchmark: A "new minimum compensation standard" of $15,000. Per course. Including benefits.

Since getting into the game a few years ago, the Service Employees International Union has won elections covering about 24,000 contingent faculty across 25 campuses. That's fitting, considering that the union specializes in organizing low-wage sectors, like property maintenance and home health care - as well as fast-food workers, where it's run a high-profile campaign for a $15 an hour wage.

A minimum wage for adjuncts?

At the moment, the $15,000 number sounds even more outlandish than $15 did when fast food workers started asking for twice the federal minimum wage. But organizers argue that if you're teaching a full load of three courses per semester, that comes out to $90,000 in total compensation per year - just the kind of upper-middle-class salary they think people with advanced degrees should be able to expect. (Most adjuncts teach part-time, which would put them at $50,000 or $75,000 per year.)

"It's not a path to competitiveness to pay knowledge workers bottom-level wages," says Gary Rhoades, head of the Department of Educational and Policy Studies at the University of Arizona, who has assisted in various adjunct organizing efforts, including the SEIU's. "The question of what they should be paid is taking away from the fact that they are paid way too little, and here's a target we're going to go for."

credit: Washington Post

So what does the idea of a "national campaign" really amount to, in substance? SEIU says the $15,000 number isn't necessarily a firm target in contract negotiations at the schools where it represents adjuncts. That's a huge bump, and it's highly unlikely any university would grant it any time soon.

Rather, it'll be more of a "rallying cry" for organizing and bargaining campaigns. The union will provide people with budget analysis tools to make the case on their own campuses, building up to a national action of some sort on April 15 (which is separate from a national walkout scheduled for Feb. 25).

The national push on adjunct pay

Although the SEIU only has signed contracts at a handful of campuses, the early returns are positive. At Tufts, for example, adjuncts recently won a salary schedule that will build up to a minimum of $7,300 per course in 2016, plus benefits. In Washington, D.C., with contracts at three universities and negotiations underway at two more, the union is closest to being able to win a city-wide contract that would cover teachers equally as they float between campuses.

Of course, SEIU isn't the only union that represents part-time faculty. The National Education Association, American Federation of Teachers, and American Association of University Professors have folded adjuncts into their locals on many campuses - the AFT alone has 80,000 contingent faculty members, and says it will be participating in a National Adjunct Awareness Week later this month..

But the professorial unions have struggled with the perception that part-timers are a threat to full time jobs. That sometimes prompts adjuncts to go an independent route with the SEIU, which isn't coordinating with the other higher education unions in its push for a $15,000-per-course standard.

"When I started, there was a sense among some tenured faculty that contingent faculty were not our friends," says Stephanie Luce, a professor of labor studies at the City University of New York, remembering her time organizing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. "On both sides there was a mistrust. So there's definitely been a tension."

Still, all of them agree that adjunct faculty wages need to increase - in part because it might lessen the incentive for universities to replace full-time faculty with contractors. And adjunct advocates point to a steep rise in administrator salaries and multi-million dollar construction projects as evidence that it's possible to compensate the teaching workforce better without hiking tuition.

"I think it's perfectly possible to raise wages without cutting jobs, if you're doing this as part of your long term planning," Luce says. "It would be a good thing to redistribute priorities on university campuses."

Meanwhile, there are other things adjuncts can bargain for that cost less than an increase in their compensation: Longer contract terms, for example, that allow them to retain access to university resources for more than a semester at a time. Unions have also tried to give adjuncts more of a voice in university governance.

A livable wage target, though, is perhaps the most galvanizing force. "I think we need a bold demand that captures the imagination," said Kim Geron, vice president of the California Faculty Association, on yesterday's SEIU call.

[Lydia DePillis is a reporter focusing on labor, business, and housing. She previously worked at The New Republic and the Washington City Paper. She's from Seattle.]

Spread the word