One Florida man’s unemployment claim could help take down a unicorn.

In April, Darrin McGillis filed for unemployment benefits from Uber, claiming that he was unable to continue driving for the company after his vehicle was damaged. Uber is already facing a handful of lawsuits alleging that drivers should be classified, treated and paid as employees, but McGillis effectively jumped the line. With his claim approved by the state, he is effectively Uber’s first employee driver — and a forerunner of likely more legal trouble to come for the growing app-based service economy that relies on legions of underpaid and underprotected contract workers in order to boost their profits.

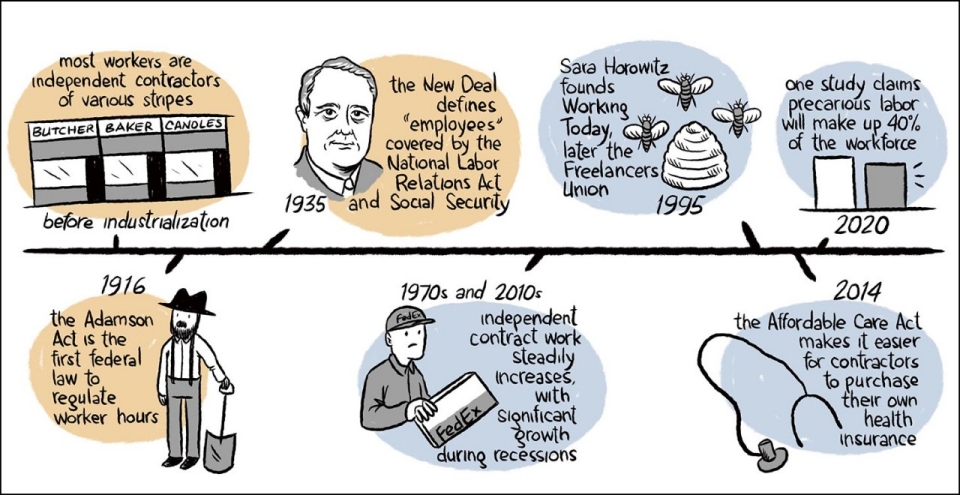

The companies of the gig economy, the on-demand economy, the 1099 economy — whatever you want to call it — have proved the most financially successful and most ethically and legally vexing of Silicon Valley’s recent startup surge. The apps may be new, but the contract work arrangement keeping these companies humming is hardly a unique or recent innovation. Hiring contractors to lower tax and legal liabilities has been a business strategy for decades. Taxi drivers were freelancers long before Uber disrupted personal vehicle travel, and they joined blue- and white-collar freelance workers across a variety of industries, from home health aides to truck drivers to engineers.

Potential class-action lawsuits like the ones pending against Lyft and Uber in California may chasten the fast-growing app-based service economy and raise awareness of worker misclassification. But the other millions of freelancers who bear the higher cost of independence with few if any of the protections that come from having a staff job will be as precarious as ever without reforms.

It’s difficult to quantify freelance work when no one seems to agree what qualifies as such. The Freelancers Union claims there are 43 million independent workers in the U.S., while the Bureau of Labor Statistics counts only 14 million. Depending on whether you include temps, on-call workers and part-time workers, these numbers can change greatly — 15 to 35 percent of the labor force. Regardless of the criteria, this population is steadily increasing.

One reason is companies like Uber. A freelance labor model allows companies to keep tax costs down and prevents workers from unionizing, since they are not protected by the 1935 National Labor Relations Act. Since 1987, the Internal Revenue Service has used a 20-point checklist to determine whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor, but the list still leaves loopholes and room for interpretation. Long before the sharing economy became San Francisco’s fever dream, federal and state agencies were cracking down on employee misclassification. A Gawker staffer made waves when she successfully received unemployment after being laid off, despite having been considered a freelancer for the news and gossip website. Not long after, workers won lawsuits against FedEx, Lowe’s and a long list of strip clubs. A suit against Google is pending.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Freelancers Union and other organizations say most contract workers are wholly satisfied with their freelance arrangements, according to their informal surveys. Proponents of the shift away from traditional employment claim freelancing’s growing popularity is due to young people embracing entrepreneurial work as opposed to traditional careers. There remains a prevailing sense that independent work is the true American dream — even though it will probably prevent you from achieving that other true American dream, homeownership, because banks tend to turn down mortgage applications from the self-employed.

Last year more than 23 million people declared self-employment income, with median earnings totaling well under $25,000, compared with median employee income of more than $28,000. Corporate entrepreneurship is rewarded with lower tax rates, but the self-employed enjoy none of those benefits, instead paying an additional 7.5 percent in income tax compared with employees. They cannot qualify for an earned income tax credit. They have no guarantee of equal protection under laws mandating minimum wages, sick leave or family leave, nor do they have protection against workplace discrimination, harassment or injury, unless they prevail in a lawsuit.

Uber and other companies may mischaracterize the nature of their workers’ independence, but many other contractors clearly don’t meet the Internal Revenue Service’s definition of “employee.”

This loophole is not in the spirit of upholding hard-fought labor protections or fostering American entrepreneurship. The contract arrangement that supposedly empowers millions of American workers is actually crippling them. While misclassification lawsuits may do much to help workers at some companies, they do nothing to reform employment law written and implemented in a different era of work.

Uber faces a strong case from thousands of their “freelance” workers who look just like employees. But the company is right about one thing: Our laws weren’t written with this economy in mind. As long as there is money to be saved by shifting risk and responsibility to workers, corporations will do it. Laws protecting workers must be uncoupled from employers. Even if work is flexible, rights never should be.

[Susie Cagle is a journalist and an illustrator in Oakland, California. She has reported on politics and technology recently for The Guardian, Medium, Wired.com and other publications. She can be reached via Twitter @susie_c.]

Spread the word