Occasionally comments on the articles in this series question why we discuss cases decided decades ago. Our purpose is to raise awareness of the ways in which the National Labor Relations Act has been "judicially amended" to hurt workers' rights.

As a result of judicial amendments, many today see the law as powerless. But the NLRA would not be powerless if it were interpreted as written and as Congress intended. The law still has the power to transform labor relations and give employees fair treatment, if only we will defend that power.

These judicial "interpretations", many made long ago when unions were stronger and union membership was much higher, contributed to the decline of unionization and persist in their devastating effects in today's economic climate. The erosion of NLRA rights through past and current "interpretations" continues to deprive workers of their rights and weaken unions. Today's article discusses two recent decisions that erode employee rights.

Last week, we discussed the 1991 decision in Lechmere, which narrowed the NLRA's definition of employee to bar employees who did not work for Lechmere from coming onto Lechmere's shopping center property to talk to Lechmere's employees about the benefits of unionizing.

Two new court of appeals cases keep employees in the dark about their rights by striking down the NLRB's requirement that employers post notices telling employees about their rights under the National Labor Relations Act.

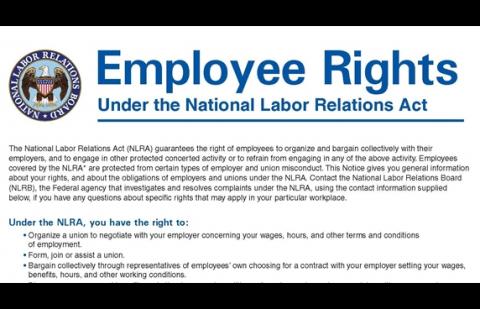

In 2011, the National Labor Relations Board, which enforces the National Labor Relations Act, issued a rule requiring employers to post a notice of employees' NLRA rights. There is no question that the NLRB has the legal power to make a rule requiring notice postings. The law clearly authorizes the NLRB to issue "such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the provisions of this Act." The proposed notice advised employees of their NLRA rights to organize unions and give mutual aid to other employees.

The notice was carefully drafted not to be one-sided, and it identified illegal conduct by both employers and unions. The purpose of the notice was clearly to educate employees about their rights.

The rule was immediately challenged by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, the National Association of Manufacturers and the Chamber of Commerce. Both the District of Columbia Court of Appeals and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the employer groups that the Board could not require employers to post this notice.

Both courts held that the NLRB did not have the authority to require employers to post a government notice to educate employees about their rights. However, the law expressly gives the NLRB the authority to make rules to carry out the law, and Congress charged the NLRB with the responsibility to enforce employees' NLRA rights. If employees do not know what their rights are, they cannot know when their rights are being violated.

The DC court found that the law violated the employer's free speech rights. Although some people claim that S8(c) of the NLRA gives employers a right of free speech, in fact, the law says nothing of the sort. All 8(c) says is that speech - and not just speech by employers - does not violate the NLRA as long as the speech does not threaten employees or promise a bribe: "The expressing of any views, argument, or opinion, or the dissemination thereof, whether in written, printed, graphic, or visual form, shall not constitute or be evidence of an unfair labor practice under any of the provisions of this Act, if such expression contains no threat of reprisal or force or promise of benefit."

Posting the notice does not prevent employers from making anti-union statements and or forcing their employees to listen to anti-union speeches. The notice does not impact such employer speech at all.

As a result of the gross misinterpretation of 8(c), free speech protections are stretched to protect employers and to prevent employees from learning about their legal rights. Once again, as in Lechmere, the courts have distorted the law to keep employees from getting information about their rights.

Contrast these cases with what happens to unions. The NLRB regularly forces unions to speak against their will. Unions must give employees formal notice that they don't have to pay union dues and must tell employees how to object to dues payment. Unions must also give employees detailed information about how the union spends its money to help employees with legal challenges to dues payment funded by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Fund.

And the same organizations that argued that the NLRB did not have the authority to issue the rule informing employees of their rights made the opposite argument about a rule the NLRB proposed twenty years ago to notify employees that they could refuse to pay full union dues.

Under the courts' "interpretation" of the NLRA, employees get information about not paying union dues, but are denied information about their NLRA rights and the benefits of unionization and making common cause with employees of other employers.

It is hard to understand why employers would challenge these notice postings and why they would fight them up through the courts of appeals. The cost of each case must be many thousands of dollars, and notice postings about other employee legal rights have been standard for decades. Employers do not post these notices willingly, but they accept that the law requires them to inform employees about their rights.

Why are employers afraid of this law? What would happen if employees could easily learn about their rights to join unions? Could we see a resurgence of employee power that would let employees share in the wealth employers gain from the workers efforts? Copyright, Truthout. Used with permission from the authors.

Spread the word