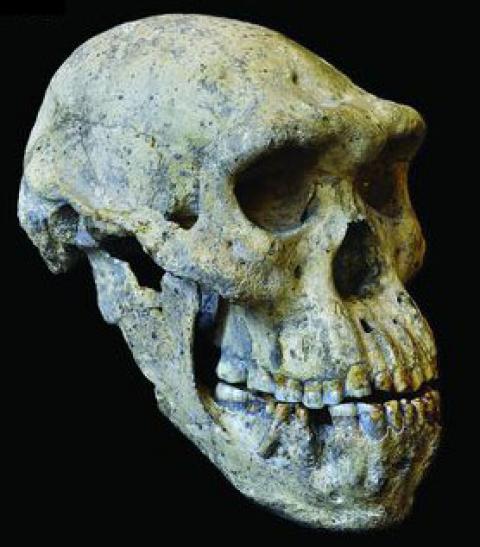

A new paper on the newest skull from the Lower Paleolithic site of Dmanisi (Georgia) is out in Science this afternoon (Lordkipanidze, et al. 2013)1 (the accompanying Science news story, from Ann Gibbons, is here). This is a spectacular specimen and I am very excited to see the research being published. I had the tremendous privilege of being at the site the day the fossil was first uncovered in 2005, and watched it as it slowly emerged and was eventually removed during that field season.

Not only is it a fantastic specimen (meticulously prepared by Gocha Kiladze and Yoel Rak), but it is associated with my favorite fossil in the hominin fossil record, the Dmanisi 2600 mandible. Dmanisi now has produced five relatively complete crania, four of which have associated mandibular remains, in addition to the post-cranial remains of several other individuals. It is not an overstatement to say that Dmanisi may be the most important single locality anywhere in the pre-1 million year hominin fossil record. I will have much more to say about this specimen and the new work in the coming days and weeks, but lets start with a few of the basics.

Why is Dmanisi important, and what does this new specimen add?

Dmanisi provides the best window we have as to what normal variation looks like in the early Homo fossil record. Dated to between 1.81-1.76 million years, the site sits in the midst of some of the most important fossil sequences in the human fossil record (i.e. Koobi Fora and the Turkana Basin, Olduvai Gorge). But unlike those African sites, the fossils from Dmanisi come from a single locality, with all of the fossil hominins coming from a narrow slice of time within that horizon.

In addition to everything coming from the same deposits, the fossils themselves represent multiple skeletal elements of multiple individuals. Recovering multiple elements from single individuals gives you a much richer window into the biology of these extinct specimens. This is why “Lucy” (i.e. A.L. 288-1), the partial skeleton of an adult, female Australopithecus afarensis, found in Ethiopia in 1974, was such a significant find. Dmanisi has the potential to produce a set of five Lucys (or more).

So Dmanisi has yielded a remarkable set of fossils from the same time and place. Adding to the bonanza, the fossils represent a set of individuals ranging in age (from middle/late adolescence to advanced adult) and encompassing males and females (though some might disagree about the specific designations). In other words, we have young and old individuals, male and female individuals, well-preserved, from the same time and place. Go out onto the street and look around at the people you see. Most of what distinguishes them in terms of their anatomy is their age and sex. If you wanted to construct a window on what kind of variation exists in fossil populations of early Homo, you would be hard pressed to engineer a better site.

And what does that window show?….variation. Lots of it. The existence of the extraordinarily large D2600 mandible was a pretty good preview of what to expect, but even it undersells the true picture of variation at the site. I will save the details for another post, but the new skull means we no longer have to guess as to the face that might accompany that large (presumably male) D2600 jaw.

So what does all this variation mean?

In a paleoanthropological context, we study variation in order to understand how evolution has acted in our past. The first step in this process, when possible, is to try and determine what exactly you are analyzing. And in this, there are different approaches. Some prefer to identify species differences first, so as to have a control over taxonomy first and foremost. This makes sense. Species are a real biological entity, so using them as the basis for future analyses seems like a good starting point.

However, the variation encompassed by any given species can be divided into different components. The two most significant components of variation within a population, as outlined above, are who happens to individuals as they develop throughout life and, at least in humans and many other sexually dimorphic primates, what differences typically exist between males and females. The challenge with starting out by identifying species, is that in order to do so, you must assume some kind of pattern of development and sexual dimorphism. An alternative approach is to begin by asking questions about intraspecific variation (i.e. age, sex, geography). Trying to understand what normal variation looks like within a species by testing hypotheses about the processes (development, sexual differentiation) that give rise to that variation allows us to construct a hypothesis about taxonomy based on more basal aspects of variation. This approach is not necessarily possible with every fossil sample, but a site like Dmanisi, with multiple individuals from the same time and place, is ideal for such an analysis. Indeed, this is the approach I have taken to the Dmanisi hominins since my dissertation (.pdf)2.

The authors of this new study make the argument that the Dmanisi variation is consistent with variation from a single “paleodeme,” or fossil population, from a single species1. The Dmanisi sample comes from one species of early Homo. This is consistent with previous work by the team, including my own work focused on the mandibles. The support for this view is the pattern of preserved morphology in the specimens as well as the geoarchaeological data that place these specimens in the same place and time. Despite the large range of variation encompassed by Dmanisi, it would require special pleading to argue for multiple species at this point.

One of the authors of the new Dmanisi study, Dr. Ani Margvelashvili, was also the lead author of a paper last week that appeared in PNAS on the Dmanisi mandibles (Margvelashvili, et al. 2013)3. Her approach was to examine the seemingly large amount of variation in the Dmanisi mandibles–a topic I have also examined from a different perspective (Van Arsdale & Lordkipanidze, 2012)4–from the perspective of normal dental development and wear. Again, the results highlight the important ways in which normal processes that shape variation at the population level play out within the Dmanisi sample.

The value and significance of Dmanisi extends far beyond Georgia. The window on variation at Dmanisi can be applied to the rich fossil samples from East Africa and elsewhere. When the authors of this study make that step, they determine that we have likely be over-taxonomizing, or relying too much on species identification and diversity to explain the variation we observe in fossils of this time period. All the fossil variation that in East Africa gets divided by some into Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo ergaster, and Homo erectus, because the specimens are too variable to represent a single species, viewed from Dmanisi, suddenly look like a single evolving lineage. Or at least, make it harder to reject that idea as a starting hypothesis. Indeed, this is the exact conclusion I reached in a paper published earlier this year, again utilizing a different approach (Van Arsdale & Wolpoff, 2013)5.

I will have much more to say about this paper, and these fossils, and the specific details of my own view of these remains. It will be interesting to see how much the current paper shifts the thinking on issues related to early Homo. In the meantime, enjoy this fantastic new fossil and the hard work that went into this paper by a large group of researchers!

*****

1. Lordkipanidze, D., Ponce de León, M., Margvelashvili, A., et al. (2013) “A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo” Science 342:326-331.

2. Van Arsdale, A. (2006). “Mandibular variation in early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia”

Department of Anthropology, Ph.D. dissertation. University of Michigan

3. Margvelashvili, A., Zollikofer, C., Lordkipanidze, D., et al. (2013). “Tooth wear and dentoalveolar remodeling are key factors of morphological variation in the Dmanisi mandibles” PNAS October 7, 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316052110

4. Van Arsdale, A. and D. Lordkipanidze (2012). “A quantitative assessment of mandibular variation in the Dmanisi hominins” Paleoanthropology 134-144.

5. Van Arsdale, A. and M. Wolpoff (2013). “A single Lineage in early Pleistocene Homo: Size variation continuity in early Pleistocene Homo crania from East Africa and Georgia” Evolution 67(3):841-850.

Spread the word