In the spirit of Thanksgiving and sharing a warm meal with loved ones, we’d like to take a moment to give some social credit to our loving, faithful, and clever furry friends. Researchers have been investigating the question of whether animals can eavesdrop—or listen in on third-party interactions—for some time, and evidence of potential eavesdropping has been identified in dogs and other mammals, fish, and birds.

Dogs are especially good candidates for studying eavesdropping because they are social animals and have been domesticated, so they are accustomed to interacting with humans day-in and day-out. Most dog owners know how well their dogs can “read” them, and some might argue that their dogs can do this better than other people they know. Researchers have also confirmed that dogs can recognize human emotions, facial expressions, and friendliness versus hostility, the latter even in strangers.

In a more nuanced form of social interaction, dogs have been shown to prefer certain people over others depending on the outcome of third-party interactions. To further investigate how dogs respond to interactions among people, the authors of this recently published PLOS ONE article asked whether dogs can develop a preference for or against givers, or “donors,” in a “begging” interaction between people.

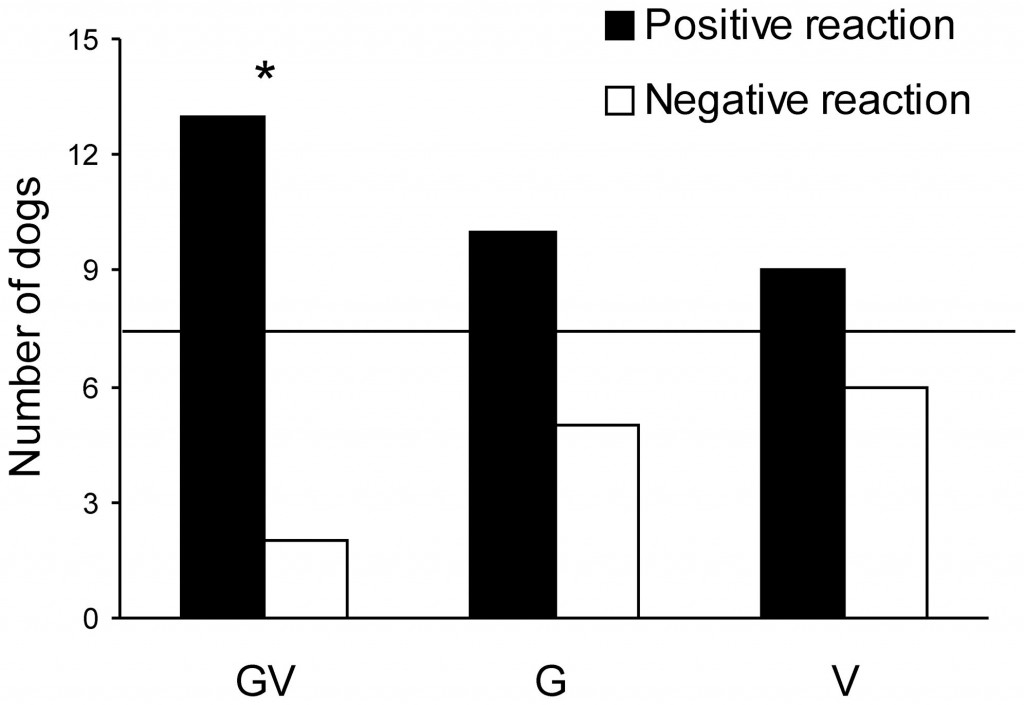

The study recruited 72 dogs of various breeds and sizes and put them in a testing environment that either resembled a home or a dog care facility. While the dog watched from across the room, two human assistants acted as “donors” (females, pictured above) who offered food to a “beggar” (male, above), and the beggar either reacted positively or negatively to the offered food. The extent of the reaction was controlled to try to determine which social cues the dog was picking up on: gesture + verbal (GV), gesture only (G), or verbal (V) only.

In the GV group positive scenario, the beggar received a yummy corn flake, ate it, and said “So tasty!”; in the negative scenario, the beggar said “So ugly!” gave the corn flake back, and then turned his back. The G and V groups differed in that they isolated the gesture and verbal components, respectively. After the beggar left, the dog was released and had 10 seconds to decide between the donors, who did not signal the dog in any way. Dogs that did not make a choice were removed from the analysis.

As the results below show, dogs were more likely to choose the donor who received a positive reaction; the authors also noted that the dogs tended to watch or gaze at the donor who received a positive reaction longer than the donor who received a negative reaction. However, the authors state that both gesture and verbal cues (the GV group) were required to show a reliable difference among the groups.

Although these results alone are not conclusive, as it is difficult to control for all the variables affecting these scenarios (e.g., the authors note that dogs chose randomly if the donors switched places), the authors suggest that the dogs may have attributed a “reputation” to the donor based on the beggar’s reaction, where both gesture and verbal cues were required for the dog to make this association.

While not the same as a scientific experiment, it might be fun to “test” your dog in various eavesdropping scenarios, especially in relation to available food* on the Thanksgiving table.

Happy Thanksgiving from PLOS ONE!

Citation: Freidin E, Putrino N, D’Orazio M, Bentosela M (2013) Dogs’ Eavesdropping from People’s Reactions in Third Party Interactions. PLoS ONE 8(11): e79198. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079198

Image Credits: Figure 1 by carterse, Figures 2 and 3 from the article

*food safe for pets to eat, of course!

Michelle Dohm is Associate Editor of PLOS ONE

Spread the word