The greening of American energy is both real and profound. Since President Obama took office, the nation's solar capacity has increased more than tenfold. Wind power has more than doubled, to 60,000 megawatts – enough to power nearly 20 million homes. Thanks to aggressive new fuel-efficiency standards, the nation's drivers are burning nearly 5 billion fewer gallons of gasoline a year than in 2008. The boom in cheap natural gas, meanwhile, has disrupted the coal industry. Coal-power generation, though still the nation's top source of electricity, is off nearly 20 percent since 2008. More than 150 coal plants have already been shuttered, and the EPA is expected to issue regulations in June that will limit emissions from existing coal facilities. These rules should accelerate the shift to natural gas, which – fracking's risks to groundwater aside – generates half the greenhouse pollution of coal.

See the 10 Dumbest Things Ever Said About Global Warming

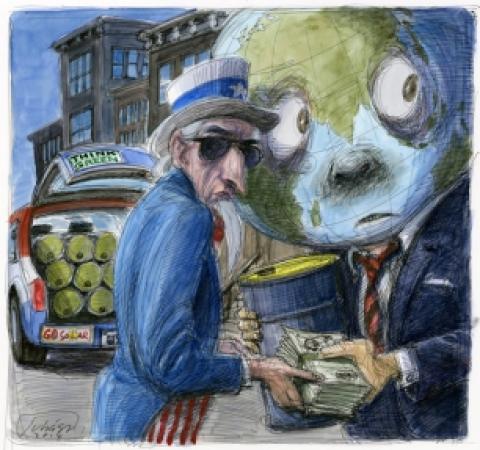

But there's a flip side to this American success story. Even as our nation is pivoting toward a more sustainable energy future, America's oil and coal corporations are racing to position the country as the planet's dirty-energy dealer – supplying the developing world with cut-rate, high-polluting, climate-damaging fuels. Much like tobacco companies did in the 1990s – when new taxes, regulations and rising consumer awareness undercut domestic demand – Big Carbon is turning to lucrative new markets in booming Asian economies where regulations are looser. Worse, the White House has quietly championed this dirty-energy trade.

"The Obama administration wants to be seen as a climate leader, but there is no source of fossil fuel that it is prepared to leave in the ground," says Lorne Stockman, research director for Oil Change International. "Coal, gas, refinery products – crude oil is the last frontier on this. You want it? We're going to export it."

When the winds kicked up over the Detroit river last spring, city residents confronted a new toxic hazard: swirling clouds of soot taking flight from a mysterious black dune piled high along the city's industrial waterfront. By fall, similar dark clouds were settling over Chicago's South Side – this time from heaping piles along the Calumet River. The pollution in both cities made national headlines – and created a dubious coming-out party for petroleum coke, or "petcoke," a filthy byproduct of refining gasoline and diesel from Canadian tar-sands crude. Despite the controversy over Keystone XL – the stalled pipeline project that would move diluted tar-sands bitumen to refineries on the Gulf Coast – the Canadian crude is already a large and growing part of our energy mix. American refineries, primarily in the Midwest, processed 1.65 million barrels a day in 2012 – up 40 percent from 2010.

Global Warming's Terrifying New Math

Converting tar-sands oil into usable fuels requires a huge amount of energy, and much of the black gunk that's refined out of the crude in this process ends up as petroleum coke. Petcoke is like concentrated coal – denser and dirtier than anything that comes out of a mine. It can be burned just like coal to produce power, but petcoke emits up to 15 percent more climate pollution. (It also contains up to 12 times as much sulfur, not to mention a slew of heavy metals.) In Canada, the stuff is largely treated like a waste product; the country has stockpiled nearly 80 million tons of it. Here in the U.S., petcoke is sometimes burned in coal plants, but it's so filthy that the EPA has stopped issuing any new licenses for its use as fuel. "Literally, in terms of climate change," says Stockman, "it's the dirtiest fuel on the planet."

With domestic petcoke consumption plummeting – by nearly half since Obama took office – American energy companies have seized on the substance as a coal alternative for export. The market price for petcoke is about one-third that of coal. According to a State Department analysis, that makes American-produced petcoke "less expensive, including the shipping, than China's coal." Petcoke exports have surged by one-third since 2008, to 33.4 million metric tons; China is now the top consumer, and demand is exploding. Through the first nine months of 2013, Chinese imports were running 50 percent higher than in 2012.

No surprise: The Koch brothers are in the middle of this market. Koch Carbon, a subsidiary of Koch Industries, was the owner of the Detroit dune, since sold off to an international buyer. But it's a third Koch brother, Billy, who is the petcoke king. William Koch is the CEO of Oxbow Carbon, which describes itself as "the worldwide leader in fuel-grade petcoke sourcing and sales" – trading 11 million tons per year.

Read Our Feature On the Arctic Ice Crisis

With dirty Canadian crude imports on the rise, U.S. refineries have been retooling to produce even more petcoke. A BP refinery on the outskirts of Chicago just tripled its coking capacity and is now the world's second-largest source of the black gunk. But the Promised Land of petcoke refining is on the Gulf Coast – which is part of why Big Oil is so hot to complete the Keystone XL pipeline. The Texas and Louisiana refineries that would process Keystone crude can produce a petcoke pile the size of the Great Pyramid of Giza every year, which, when burned, would produce more than 18 million tons of carbon pollution.

Despite the dangers of petcoke, the Obama administration has turned a blind eye to its proliferation. A 2011 State Department environmental-impact study of Keystone XL, commissioned under then-Secretary Hillary Clinton, treated petcoke as if it were an inert byproduct, and failed to consider its end use as a fuel when calculating the greenhouse impacts of the pipeline. According to the EPA, that decision led State to lowball the pipeline's associated emissions by as much as 30 percent.

In 2013, the post-Hillary State Department revised that assessment, conceding that petcoke "significantly increases" the emissions associated with tar sands. However, State punted on the big issue of climate pollution, maintaining that Keystone XL won't create a net increase because the Canadian crude would reach Gulf refineries with or without the pipeline.

A joint letter by Rep. Henry Waxman and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, chairs of the Bicameral Task Force on Climate Change, blasted State's conclusion as "fundamentally flawed" and "contrary to basic economics" – noting that it would take a new forest the size of West Virginia to fully offset the carbon emissions Keystone XL would bring to market.

The tar-sands boom has the united states poised to become a top player in the global-export market for gasoline and diesel. And Obama's top trade ambassador has been working behind the scenes to make sure that our climate-conscious European allies don't shutter their markets to fuels refined from the filthy Canadian crude.

The U.S. trade representative, Ambassador Michael Froman, is a protégé of former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and a top member of the president's inner circle. Froman was confirmed last June to his current trade post, where he's under direct orders from the president to "open new markets for American businesses." His nomination was opposed by only four senators – chiefly Massachusetts Democrat Elizabeth Warren, who faulted Froman for refusing to commit to even the paltry standard for transparency in trade talks set by the George W. Bush administration. Warren was right to be concerned. In backroom negotiations, Froman has worked to undermine new European Union fuel standards intended to lower the continent's carbon emissions. The European standards would work, in part, by grading the carbon toxicity of various crude oils. They logically propose placing polluting tar-sands oil in a carbon class all by itself; on its path from a pit mine to the filling station, a gallon of tar-sands gas is responsible for 81 percent more climate pollution than the average gallon of regular. But instead of respecting the EU's commitment to slow global warming, Froman has worked to force North America's dirtiest petrol into the tanks of Europe's Volkswagens, Peugeots and lorries.

His hardball tactics were revealed in obscure written congressional testimony last year. In a question to Froman, Rep. Kevin Brady, an oil-friendly Texas Republican, slammed the European proposal as a "discriminatory, environmentally unjustified" trade barrier. Froman responded, "I share your concerns," and described his work to "press the Commission to take the views of . . . U.S. refiners under consideration." He explained how he had turned the standards into a point of contention in negotiations of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership – a major free-trade pact being hammered out between the U.S. and the EU. Last October, Froman's team even went before the World Trade Organization to demand that all globally traded petroleum products be treated "without discrimination."

Froman's dirty-energy advocacy provoked an angry letter last December from the Bicameral Climate Change Task Force – prominently co-signed by Warren. It blasted the ambassador's efforts to "undercut" the EU's climate goals as well as his "shortsighted view of the United States' economic interests." Citing the projected $70 billion in adverse climate effects from exploitation of tar-sands crude, the task force demanded Froman justify his "troubling" actions in the context of the United States' "long-term economic well-being." The ambassador's office has not responded.

"We're telling the world on the one hand that it's time for leadership from us on facing up to carbon pollution," says Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island. "While on the other we're saying, 'Hey, here, buy our high-carbon-pollution fuels.'"

If Big Oil has its way, the United States could soon return to the business of exporting not only refined petroleum products but crude oil itself – a practice that's been illegal since the oil shocks of the 1970s. The crude-oil-export ban has been the linchpin of U.S. energy security for more than a generation. With narrow exceptions for Alaskan crude and exports to Canada, the law requires that oil drilled here must be refined here – helping to insulate American drivers from disruptions in oil fields of the Middle East. But the unexpected boom in fracked crude from North Dakota and Texas has transformed this long-uncontroversial law into a bugbear for domestic drillers – who now see American energy independence as a threat to their profit margins.

When the Keystone XL pipeline was first proposed in 2007, the accepted notion was that Gulf Coast refineries would be able to process all the crude that the pipeline could carry. But the nation's energy picture has since changed dramatically. Thanks to advances in fracking technology, North Dakota and Texas are bringing millions of barrels of "sweet" – low-sulfur, easily refined – crude to the market every day.

In this new reality, the fixed flow from a pipeline like Keystone XL, carrying more than 1.5 million barrels of Canadian crude to the Gulf Coast every day, is going to create excess supply. The surplus tar-sands crude, as much as 400,000 barrels per day, will have to be shipped out of the Gulf to the global market. "There is a limit to how much the Gulf Coast refiners can soak up," said Esa Ramasamy, of the energy-information service Platts, in a recent presentation. "The Canadian crudes cannot go back up into Canada again. They will have to go out."

An export ban or not, it will likely happen: As long as it's not "commingled" with American crude, Canadian crude, despite its transit through the United States, remains Canadian.

The new flood of domestic crude, meanwhile, is straining U.S. refining capacity, producing a nearly $10-per-barrel discount for U.S. oil compared to the global average for sweet crude. America's domestic drillers are desperate to fetch higher prices on the global market. (Exxon, the Chamber of Commerce and key senators like Alaska Republican Lisa Murkowski have just launched a media offensive to kill the export ban altogether.)

In addition to promoting energy independence, the export ban now has the virtue of limiting the pace at which American drillers exploit the continent's newfound climate-toxic oil riches. Ending the ban would not only hurt U.S. consumers by wiping out the home-oil discount, it would also boost the profits of domestic-oil companies and hasten exploration of now-marginal deposits. "Lifting the oil-export ban is simply climate denial in a new, and very dangerous, form," says Steve Kretzmann, Oil Change International's executive director.

Nonetheless, Obama's new energy secretary, Ernest Moniz, told reporters at a recent energy conference that the ban is a relic and ought to be re-examined "in the context of what is now an energy world that is no longer like the 1970s."

The greatest success story in the greening of American energy is the market-driven collapse of coal. Last year, American power plants burned 181 million fewer tons of coal than in the final year of the Bush administration, as power companies shifted to burning cheaper natural gas. And after years of delay, the administration finally appears to be committed to driving some regulatory nails into Big Coal's coffin: In January, the EPA published a draft rule that's likely to end the construction of new coal plants by requiring cost-prohibitive carbon-capture technology. This summer, the agency is expected to introduce climate-pollution rules for existing plants that should hasten the adoption of natural gas.

With the freefall in domestic demand, industry giants like Peabody are desperate to turn American coal into a global export – targeting booming Asian economies that are powering their growth with dirty fuel. China now consumes nearly as much coal as the rest of the world combined, and its demand is projected to grow by nearly 40 percent by the end of the decade. "China's demand," according to William Durbin, head of global markets for the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, "will almost single-handedly propel the growth of coal."

Since Obama took office, American coal exports are up more than 50 percent. And Big Coal has designs to more than double that tonnage by opening a direct export route to Asia, shipping coal strip-mined from the Powder River Basin, in Wyoming and Montana, by rail to a network of planned export terminals in the Pacific Northwest, and then by sea to China. These new coal exports have received far less attention than Keystone XL, but would unleash a carbon bomb nearly identical to the greenhouse pollution attributed to the pipeline.

After inking a 2011 deal to export 24 million tons of Powder River Basin coal through the planned Gateway Pacific Terminal at Cherry Point in Washington, Peabody Coal CEO Gregory Boyce gushed, "We're opening the door to a new era of U.S. exports from the nation's largest and most productive coal region to the world's best market for coal."

Last March, John Kitzhaber and Jay Inslee, the governors of Oregon and Washington, respectively, wrote to the White House expressing near disbelief that the administration seemed prepared to let Big Coal's dreams come true. "It is hard to conceive that the federal government would ignore the inevitable consequences of coal leasing and coal export," they wrote. Coal passing through Pacific Northwest terminals would produce, they argued, "climate impacts in the United States that dwarf those of almost any other action the federal government could take in the foreseeable future."

But the administration refused to intervene. Appearing before Congress last June, the acting regulatory chief of the Army Corps of Engineers announced that climate pollution would not factor in the evaluation of permits for the export terminals. The burning of American coal in Asia, she testified, was "too far removed" to be considered.

Even more troubling, the administration opened up more than 300 million tons of coal in the Powder River Basin to bidding by the coal companies last year. The coal is on government land; it belongs to the public. Yet the leasing practices of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) are so flawed that one independent study estimates that taxpayers have been fleeced of $30 billion over the past three decades. In the past, that stealth subsidy to Big Coal at least helped create cheap power for American homes and businesses. Today, the administration has put American taxpayers in the position of subsidizing coal destined to fuel the growth of our nation's fiercest, and carbon-filthiest, economic rival.

In the battle to prevent the United States from fueling the developing world's global-warming binge, the deck is stacked against climate hawks. The fossil-fuel industry remains the single most powerful special interest in Washington, having successfully ball-gagged the entire Republican Party on global warming. More insidiously, the macroeconomic indicators by which the economy – and any presidency – are measured can be cheaply inflated through dirty-energy exports, which boost GDP and narrow the trade deficit.

But here's the surprise: Climate activists are more than holding their own. Keystone XL is on an indefinite hold, and Whitehouse says he's "optimistic" that the pipeline won't gain approval on the watch of new Secretary of State John Kerry. Likewise, Obama's Powder River Basin initiatives seem to be going nowhere in the face of strong regional and national opposition. Even Wall Street is getting cold feet on coal. In January, Goldman Sachs dumped its stake in the Cherry Point, Washington, terminal once celebrated by Peabody Coal's CEO as emblematic of his industry's future. And with no clear path to China, coal companies themselves are pulling back. In two BLM auctions last summer, one failed to solicit any bids by coal companies; the other received a single bid – and it was too low for even the famously coal-friendly BLM to accept.

But preventing America from morphing into the world's dirty-energy hub will likely require something more: a competitive Democratic primary for 2016. By all outward indications, the Clinton regime-in-waiting is even more supportive of the dirty-energy trade than the Obama White House. Bill Clinton is a vocal proponent of the Keystone XL pipeline, calling on America to "embrace it." During Hillary Clinton's reign as secretary of state, the department outsourced its flawed environmental assessment of Keystone XL to a longtime contractor for the pipeline's builder, TransCanada – whose top lobbyist just happened to have served as a deputy manager for Clinton's 2008 presidential run. Clinton herself, in a 2010 appearance at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, sounded fatalistic about bringing tar sands to market: "We're either going to be dependent on dirty oil from the Gulf, or dependent on dirty oil from Canada," she said.

In a contested primary, the issue of constraining the nation's polluting exports is likely to emerge as a significant fault line between Clinton and whomever emerges to represent the Elizabeth Warren wing of the Democratic Party.

A credible challenger need not derail Clinton to make the difference. Recall that both Clinton and Obama began as reticent climate hawks in 2008 – even talking up the prospects of refining coal into a liquid for use as auto fuel – before the threat of John Edwards forced both candidates to commit to the ambitious goal of reducing climate pollution by 80 percent by 2050. On the other hand, if Hillary Clinton simply cruises through the primaries, it's a safe bet that the corporate center will hold – and that North America's fossil exports are going to flow. That's a state of affairs from which the world as we know it will not soon recover.

Spread the word