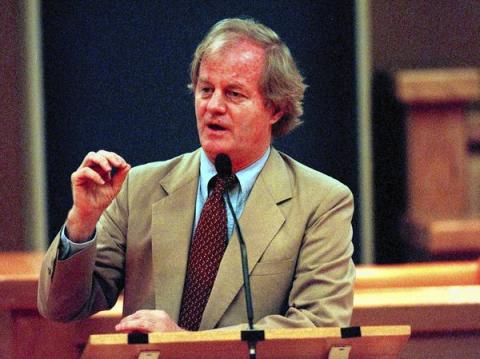

Jonathan Schell, the author, journalist and activist who wrote passionately and cogently about war and politics for more than 40 years, condemning conflicts from Vietnam to Iraq and galvanizing the anti-nuclear movement with his horrifyingly detailed bestseller, "The Fate of the Earth," died Tuesday at his home in New York City. He was 70.

The cause was cancer, according to Schell's companion, Irena Gross.

With unrelenting rage and idealism, Schell focused on the consequences of violence in essays and books that conveyed a hatred of war rooted in part in his firsthand observations of American military operations in Vietnam.

He was only 24 when he published his first book, "The Village of Ben Suc" (1967), a graphic account of the American assault on a small village northeast of Saigon in 1967. Schell, then a graduate student returning from studies in Japan, wangled a press pass and swooped into the hamlet with the first wave of U.S. military helicopters, then chronicled its obliteration in quiet but forceful prose.

"It was a remarkable piece of reporting and writing, particularly for one so young and so modestly experienced," New Yorker editor David Remnick wrote in a tribute Wednesday that described Schell as "an invaluable voice" of moral conscience.

As gentle in person as he was impassioned on paper, Schell was a reporter and columnist for such publications as The New Yorker, Newsday and most recently The Nation.

Among his books, "The Fate of the Earth" (1982) was his mostly widely praised. Originally published as a four-part series in the New Yorker, it opened with a detailed description of how atom bombs are made and the annihilation they would cause before proceeding to analyze the problems with deterrence theory and discourse on humanity's obligation to future generations. It appeared at an especially tense moment of the Cold War, with public sentiment for a nuclear weapons freeze growing.

"The machinery of destruction is complete, poised on a hair trigger, waiting for the 'button' to be 'pushed' by some misguided or deranged human being or for some faulty computer chip to send out the instruction to fire," Schell wrote. "That so much should be balanced on so fine a point — that the fruit of four and a half billion years can be undone in a careless moment — is a fact against which belief rebels."

Some reviewers found Schell's book shrill and overstated, including Michael Kinsley, then editor of Harper's, who pronounced it "one of the most pretentious things I've ever read." But others praised it, including critic Art Seidenbaum, who called it "the most important, dismaying book of the year" in the Los Angeles Times, which gave Schell's work a Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Schell's other works include "The Gift of Time: The Case for Abolishing Nuclear Weapons Now," "The Unconquerable World: Power, Nonviolence and the Will of the People" and "The Seventh Decade: The New Shape of Nuclear Danger." He taught at Princeton University and Wesleyan University, and was a visiting lecturer at Yale at the time of his death.

A native of New York City, Schell was born on Aug. 21, 1943, just two years before the U.S. dropped two atom bombs on Japan. He grew up in a family of thinkers and dissenters: His father, the late Orville Schell Jr., was an attorney and human rights activist. His brother, Orville Schell, is a longtime journalist and activist and former head of the journalism school at UC Berkeley.

Conscious of nuclear weapons from an early age, Jonathan Schell remembered headlines in 1953 that the Soviet Union had successfully tested a hydrogen bomb. At Harvard University, where he earned an undergraduate degree in 1965, one of his teachers was Henry Kissinger, the future secretary of state and target for the antiwar movement.

In 1967 he began two decades of writing for the New Yorker and, according to Remnick, had been editor William Shawn's choice as successor in the mid-1970s. But when Shawn was finally replaced in 1987, Schell left with him.

Later, as The Nation's "peace and disarmament correspondent," he wrote against the Iraq war, supported the Occupy Wall Street protests and called repeatedly for the elimination of nuclear weapons. On Sept. 11, 2001, he was nearby when two hijacked planes struck the World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan.

"My specific neighborhood was violated, mutilated," he reported days later. "As I write these words, the acrid, dank, rancid stink — it is the smell of death — of the still-smoking site is in my nostrils. Not that these things confer any great distinction — they are merely the local embodiment of the circumstance ... that in our age of weapons of mass destruction every square foot of our globe can become such a ground zero in a twinkling. We have long known this intellectually, but now we know it viscerally, as a nausea in the pit of the stomach that is unlikely to go away. What to do to change this condition, it seems to me, is the most important of the practical tasks that the crisis requires us to perform."

In addition to Gross and brother Orville, he is survived by his wife, Elspeth; a sister, Susan Pearce; three children and two grandchildren.

Spread the word