When I teach history related to Islam or Muslims in the United States, I begin by asking students what names they associate with these terms. The list is consistent year after year: Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, and Muhammad Ali.

All of these individuals have affected U.S. history in significant ways. If we take a step back and look at the messages these figures communicate about Muslims in U.S. history, we see a story dominated by men and by the Nation of Islam. Although important, focusing solely on these stories leaves us with a skewed view of Muslims in U.S. history. Even these examples are a stretch. Most of my students reference 9/11 as the first time they heard of Muslims.

Mainstream textbooks do little to correct or supplement the biases that students learn from the media. These books distort the rich and complex place of Muslims throughout U.S. history. For example, Malik El-Shabazz (consistently referred to first by the name Malcolm X rather than the name he chose for himself before his assassination) is framed as the militant, angry black man, the opposite of the Christian, nonviolent Martin Luther King Jr. Muhammad Ali is another popular representative of Muslims in U.S. history textbooks but is misrepresented through the emphasis on his boxing career rather than his anti-racist activism against the Vietnam War.

Muslims have been part of our story from the beginning. For example, although U.S. history textbooks wouldn’t dare leave out the sanitized story of Christopher Columbus, they fail to include the Muslim-led revolt against his son, Diego, on Dec. 25, 1522. Armed with the machetes they used to cut cane, these rebels, including enslaved West African Muslims, succeeded in killing a number of colonial settlers before the insurrection was quelled; of the 15 bodies recovered, nine were Europeans. As Michael Gomez explains in Black Crescent: The Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the Americas, Muslims were among the first to resist the colonialists. In fact, colonial authorities had long seen these “Moors” as a threat. According to Sylviane Diouf, author of Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas, colonial documents between the Crown and conquistadors describe enslaved Muslims as “arrogant, disobedient, rebellious, and incorrigible.” Diouf writes that no fewer than five decrees were issued against these rebels in the first 50 years of colonization. Records from as early as 1503 confirm a request by Nicholas de Ovando, the governor of Hispaniola, to Queen Isabella asking her to restrict further shipment of enslaved Muslims because they were “a source of scandal to the Indians, and some had fled their owners.” It’s essential that students know that resistance to colonial domination has always been a part of our history—and Muslims played a role in this resistance from the earliest days.

Advertisements for people escaping slavery included names like Moosa or Mustapha, common names even among Muslims today. According to Gomez, in 1753 Mahamut (one of many spellings of Muhammad) and Abel Conder challenged the legality of their enslavement through a petition to the South Carolina government “in Arabick.” Similarly, in 1790 a number of formerly enslaved people originally from Morocco—referred to as free Moors—likewise petitioned South Carolina to secure equal rights with whites.

U.S. history textbooks generally present “slaves” as a monolithic group, absent of history, culture, and scholarship. But stories of the Muslim presence in the early United States give examples of the rich multicultural diversity among enslaved Africans.

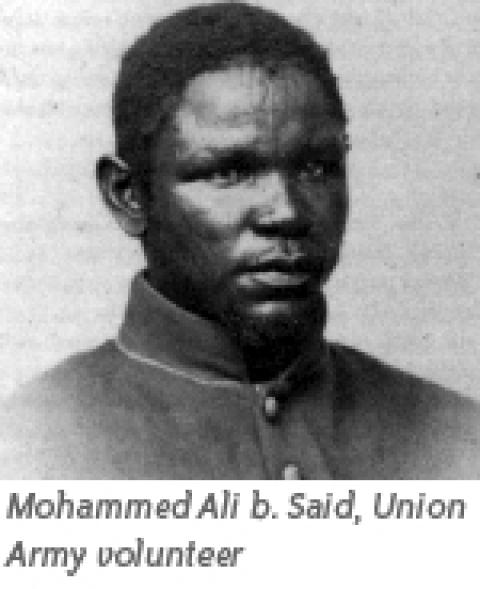

Although most of the first Muslims in the United States were brought as slaves, some came as free men. Mohammed Ali b. Said, or Nicholas Said, fought in the Civil War. He was born around 1833 in the Islamic state of Bornu near Lake Chad. He was enslaved around 1849 and sold numerous times throughout the Middle East, Russia, and Europe. He traveled to the United States as a free man in 1860 and became a teacher in Detroit. Said joined the 55th Regiment of Massachusetts Colored Volunteers and served in the Union Army until 1865.

Muslims are also part of the rich history of resistance to Jim Crow. In the 1920s, P. Nathaniel Johnson, who changed his name to Ahmad Din, led a multiracial integrated mosque in St. Louis. The Ahmadiyya Muslim community in the United States (followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who began an Islamic renewal movement in India in 1889) vocally opposed segregation, supported Marcus Garvey’s UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association), and included articles in their newspaper, The Moslem Sunrise, criticizing U.S. racism.

Muslims also participated in union activism. One of them was Nagi Daifallah, a Yemeni Muslim farmworker murdered for his participation in the 1973 California grape strike. Nagi was an active member of the UFW (United Farm Workers of America). On Aug. 15, Nagi joined a weeks-long strike in Lamont, Calif., where he worked at the nearby El Rancho Farms. Fifteen strikers met early that morning at the Smokehouse Café when Kern County Sheriff’s Department Deputy Gilbert Cooper arrived to harass the workers. The deputy targeted Nagi, who tried to run away. Cooper ran after him and smashed Nagi in the head with a long five-cell metal flashlight. Nagi’s spinal cord was severed from his skull. Two sheriff’s deputies picked Nagi up by the wrists and dragged him for 60 feet, taking no care to protect his head, which repeatedly hit the pavement, and then dumped him in the gutter. Deputies arrested workers who attempted to help Nagi, and he died shortly thereafter.

U.S. Muslims today continue the legacy of a people’s history. Linda Sarsour, executive director of the Arab American Association of New York, is an outspoken critic of stop-and-frisk and proponent of immigration reform—she was arrested in October 2013 at the national immigration reform protest in Washington, D.C. She is also at the forefront of protests against the NYPD and CIA-sponsored secret surveillance program against Muslims that began in 2001. Not only is Sarsour’s nonprofit one of the organizations targeted by the illegal spying program, so too is her children’s soccer league. The NYPD included the league in its community outreach program until further investigation found that the NYPD’s involvement was simply a way to spy on the community. As Sarsour explains in a Democracy Now! interview, “hat it does is it creates psychological warfare in our community.” Considering the fact that Muslims have been routinely disappeared by the U.S. government since 9/11, her willingness to stand up to the NYPD and CIA is even more courageous.

Students need these stories of Muslims throughout U.S. history in order to talk back to the dominant media stereotypes of Muslims as lying, violent, brown foreigners. If we gave students the historical examples in this article and more, they would realize that the history of Muslims in the United States is not limited to 9/11 and, in fact, spans from the late 15th century through today.

Alison Kysia has taught history at Northern Virginia Community College-Alexandria for six years. She is a Zinn Education Project Program Associate at Teaching for Change. This article is part of the Zinn Education Project If We Knew Our History series.

Alison Kysia has taught history at Northern Virginia Community College-Alexandria for six years. She is a Zinn Education Project Program Associate at Teaching for Change. This article is part of the Zinn Education Project If We Knew Our History series.

© 2014 The Zinn Education Project

Spread the word