I doubt many my age can greet the end of school or the warm weather without thinking about baseball. When I was young, it certainly seemed as if the nineteenth century promoters who had worked so hard to make it “the American game” had succeeded. Football remained the domain of colleges, but baseball–despite its pastoral imagery (or maybe because of it)–had become endemic to workingclass life in America. Growing up in a blue collar town dominated by the shoe industry, we not only had baseball but most of its variants, including cork ball, which developed in the narrow spaces of the warehouse and in the alleyways of the city.

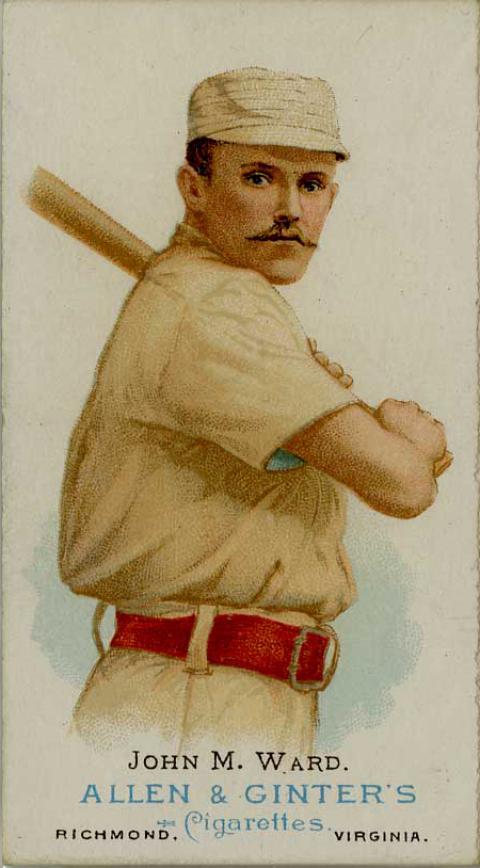

In a history often preoccupied with the jostling of owners and promoters, it’s worth remembering the contribution of John Montgomery Ward. Born at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania in 1860, he became an outstanding shortstop, a brilliant pitcher, and memorable trade unionist.

Beginning as clubs of players, baseball drew crowds which, by the 1840s and 1850s, were starting to generate considerable money by paying admission to the playing field. In short order, entrepreneurs and investors gained control of the clubs and became “owners” who did not themselves play the game. It was a process reflecting much of what happened in trades like shoemaking. The owners started a loose National Association of Professional Base Ball Players in 1869, but reorganized their National Association on a more clearly business model in 1871. In 1875, this became the National League.

That same year, Ward’s Pennsylvania State College fielded a baseball team. He had gone there two years earlier, but quickly took to the game. The athletes strained at the rigidity of the college rules and regularly found themselves in trouble. In the spring of 1877, Ward left school and took to the rails. In desperation, he took a place on a local baseball team in the railroad town of Williamsport, where he quickly developed his reputation as a pitcher, even as the state hanged Molly Macguires up the line. As tensions built towards the great 1877 rail strike, Ward found himself at Philadelphia, making his first effort to enter the new profession.

Ward entered that profession the next year. The Providence Grays signed him for the 1878 season, and he played for them for the next four years. His second year out, in 1879, he led the Grays to 46-victories, capturing the pennant. The following year, he pitched the second perfect game in major league history, though the term would not be used for another 28 years. On August 17, 1882, Ward pitched an 18-inning shutout, a record unbeaten for the longest shutout by a single pitcher. After this, he moved on to the New York Gothams or Giants.

These kinds of clubs combined some of the best college players and talent fresh off the streets of the workingclass quarters. In an age characterized by a faith in regulation–the “Progressive Era”–and the club owners began adopting rules to make baseball a gentlemen’s game and its players suitable role models. These went beyond standardizing gameplay to sanctions against rowdiness and drunkenness. They also excluded “colored” teams–defined as any team with a single “colored person” playing on it.

By then, the professional ball clubs had already begun implementing “the Five Man Rule,” which meant that even when a player’s contract ended at the close of the season, the owners could reserve its players, whose only escape would be to opt out of playing for a year. This effectively denied players the right to enter into their own contracts with a team of their choice for the coming year, though the owners could trade or dispose of them as they pleased. Such was the beginning of the so-called “reserve cause” in their contracts.

In the late summer of 1885, Ward and eight others launched the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players. The Knights of Labor had reached a peak of its power and the American Federation of Labor would be formally organized the following year. Under Ward’s leadership, the Brotherhood fearlessly advocated for the players gained following that included the clear majority of professional players.

Throughout these years, Ward also challenged the color bar, and was not alone in doing so. Almost seventy years before Jackie Robinson entered the majors, Ward and other members of the Providence team put into a game as a substitute William Edward White, a mixed-race university student from Brown to play on June 21, 1879.

The winter of 1879-80 found Ward with his own hand-picked team giving exhibition games in the South. In New Orleans, they defied all convention by playing a black team.

In 1883, the Toledo team in the short-lived Northwestern League signed Moses Fleetwood Walker, a light-skinned black man educated at Oberlin and the University of Michigan. In August, though, Adrian “Cap” Anson took his Chicago White Stockings there and flatly refused to play a team with “the nigger in.” The Toledo team refused to budge, though, and, at the last possible minute, Anson backed down. The next year, Fleet’s brother, Weldy Wilberforce Walker played on the team, which played at Louisville and Richmond, despite death threats in the old capital of the Confederacy, though Anson blocked the game scheduled with his White Stockings. Over the next few years, Fleet Walker played for Cleveland, Waterbury, and Newark. The last team, in the minor International League, included Frank Grant of Buffalo, the black man who became the best hitter in the league, as well as George Stovey, another member of the Newark outfit.

Matters came to a head in an 1887. In April, Newark team faced off in a home game against Ward’s New York team. The talent of Walker and Stovey impressed Ward tremendously–Walker actually threw out Ward when he attempted to steal a base–and the star took measures to recruit both of the black players to his team. Anson got wind of it and stirred up a press war that ended as the owners raised a more secure color bar.

The owners refused to budge on the reserve clause too. In 1890, against the backdrop of a resurgent cooperative movement, the Brotherhood finally met the intransigence of the owners by forming a league of their own. Four out of the five professionals followed Ward from the National League into their own organization. He played on Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders and, later, the Brooklyn Grooms. Samuel Gompers and officials of the AFL met with representatives of the Players’ Leagues, and some unions fined members caught attending “non-union” games.

For several years, the Players held its own, but, as with most cooperative ventures, they faced no level playing field. Their former bosses had deep pockets and access to seemingly limited amounts of capital. The National League did realize that the players’ organization included the best talent in the game. To persuade the Players’ League to dissolve and return to the owners’ clubs, the National League offered concessions on many issues. Yet, it required concessions from Ward and the players on many of the major questions under dispute, including the reserve clause, just as it had imposed a unilateral power to exclude African Americans.

The collapse of the Players’ League came in 1893. Although baseball remained a private business, the owners’ position on race won vindication only a few years later from no less lofty a body than the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1896, its decision in Plessy v. Ferguson sanctioned racial segregation in public facilities under the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

Ward, meanwhile, had quietly returned to the National League and his old team for another season. He would die in Georgia in 1925, only a few years later after another Supreme Court decision. In Federal Baseball Club v. National League, the court declared that the Sherman Antitrust Act did not apply to the organized sport, which was not an interstate trust but an “amusement.”

In the end, the same power that allowed the owners to bar blacks from the game also thwarted serious gains around the grievances of John Montgomery Ward and that pioneering generation of unionists. Nor should we simply distinguish between what they gained for those to come later from what they could have gained and should have gained. After all, what happens off the playing field has brought no reprise after the ninth inning.

Further readings:

Bryan Di Salvatore, A Clever Base-Ballist: The Life and Times of John Montgomery Ward (New York: Pantheon, 1999)

David W. Zang, Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

Mark Lause is a Professor of History at the University of Cincinnati. His most recent book is A Secret Society History of the Civil War, published in 2011 by the University of Illinois Press.

Spread the word