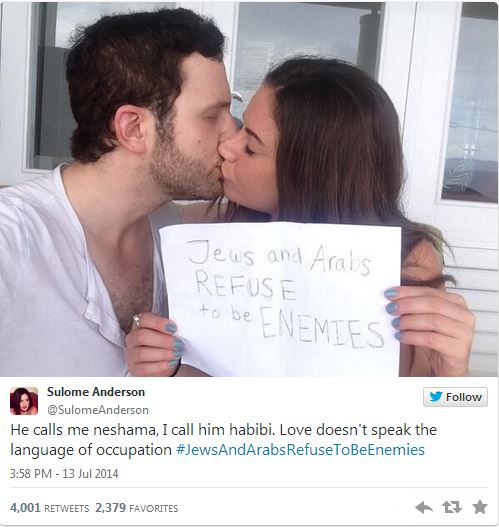

I’m Arab-American. My Boyfriend Is Jewish. A Selfie of Us Kissing Has Become a Viral Symbol of Peace.

We posted the picture without a second thought.

My boyfriend is Jewish, raised in an orthodox family, and I’m half Lebanese. Last week we were on vacation and, at the suggestion of a journalist friend, added a photo of us together in support of what was then a little-known initiative called Jews and Arabs Refuse to be Enemies. I wrote those words on a piece of paper, kissed my boyfriend, snapped a picture, and posted it on the group's Facebook page. I also tweeted it to my modest following and added this caption: “He calls me neshama, I call him habibi. Love doesn’t speak the language of occupation.”

It went viral.

The photo has been retweeted over 1,400 times. News stories and interviews followed. More and more people have posted their own pictures illustrating the message, but that image of me kissing my boyfriend has become the face of a rapidly growing internet campaign.

My journalist friend suggested we post the photo because he’s intimately familiar with the biggest stumbling block we’ve faced in our relationship: politics. He’s witnessed some of our fights and heard me complain extensively about our differing perspectives on the situation in Gaza. Jeremy, my boyfriend, who prefers his last name not be used, comes from a family that is staunch in its support of the Israeli government. He lived in Israel for some time and has dual citizenship. My mother is Lebanese, and as a journalist, I am partly based in Beirut. I’ve worked in the Palestinian refugee camps scattered across Lebanon, so I’ve seen the desperate circumstances many Palestinians face.

So, in the days leading up to the war, mounting tension between Israel and Hamas was a frequent topic of discussion between Jeremy and me. These discussions often turned into arguments and sometimes flat-out fights. Jeremy took issue with my assumptions about Israelis; I couldn’t understand why he seemed to place more emphasis on Israeli lives than Palestinian ones. But as he eventually revealed to me, he’d witnessed a bus bombing during his time in Israel. He had seen that violence from the other side.

As the region exploded into war, we started to come closer together in our opinions given the fact that we both share critical values: respect and concern for human life. I showed him some of the heart-wrenching photos coming out of Gaza; most people can’t see those tiny, broken bodies without feeling pain and regret for their short lives and the violence that took them.

I’m not saying we reach a consensus on everything now. But we do agree on something: This isn’t just about politics. This is about people. No one knows better than I the toll Middle East violence takes on ordinary people just trying to live. My father, Terry Anderson, was kidnapped in Lebanon three months before I was born in 1985, by a Shiite militia that would eventually become Hezbollah. He was held for seven years.

Despite everything, what’s always inspired me about my father is that he harbors no bitterness or even real anger for the men who took seven years of his life. On the contrary, while he doesn’t excuse what they did, he understands them in the context of the war that created them. He knows they were people too, with their own motivations and struggles, as alien and violent as they may seem. And on some level, he forgives them. Instead of dehumanizing those who have hurt you, I think you need to look at the context of their lives and understand them as human beings in order to reach any real peace, with yourself or with them.

That’s why Jeremy and I decided to take part in the Jews and Arabs Refuse to Be Enemies campaign, which was started by Abraham Gutman, an Israeli student living in New York, and his friend Dania Darwish, who is Syrian. We love that the movement emphasizes the human connections between people the world has taught to hate each other. We wanted to spread the message our relationship has taught us: We aren’t just what we believe.

Predictably, there has been a significant amount of pushback against this campaign, although surprisingly, much of it has come from the pro-Palestinian side. Some have criticized us for trivializing what’s going on in Gaza. They say this conflict isn’t about hatred between Jews and Arabs; it’s about a powerful country oppressing a weaker people. (To be clear, that’s how I feel as well.)

There hasn't been any reaction from Jeremy's family, but there's a good chance they haven't seen the photo yet. On the other hand, I've been the target of all sorts of aggressive comments on social media, with words like "bitch" and "attention whore" being spat at me; again, sadly, they've mostly been people I fundamentally agree with.

Of course, an overwhelming majority of the rhetoric and social-media chatter around Gaza has been, frankly, disgusting. One only needs to look at David Sheen’s collection of tweets about Arabs from Israeli teens to realize what happens when young people are raised to hate. And that is something that does occur on both sides.

But that’s not what our message is. We wanted to spread an idea that wouldn’t polarize, something that would be heard not just by the people who agree with us, but by those who don’t. Militancy and anger haven’t helped bring this to an end. Maybe, we thought, it was time for a different approach.

What excites me most about this campaign is that I’ve been retweeted by people I know don’t share my politics; whom I’d ordinarily be getting into online bitch-fights with. But despite our differences, they saw something in that message they could connect with, and it gives me hope.

Knowing I’m traveling to Lebanon in two weeks and will be interacting with people most likely unreceptive to the fact that I have a Jewish boyfriend, my mother has fretted to me quite a bit about this attention. She called me yesterday.

“I was afraid about this at first,” she said. “But I’ve been watching it grow, and I saw that it might change the world a little. I realized afraid was the wrong way to feel.”

Our photo going viral is scary and overwhelming. But we both know that afraid is the wrong way to feel about it.

Spread the word