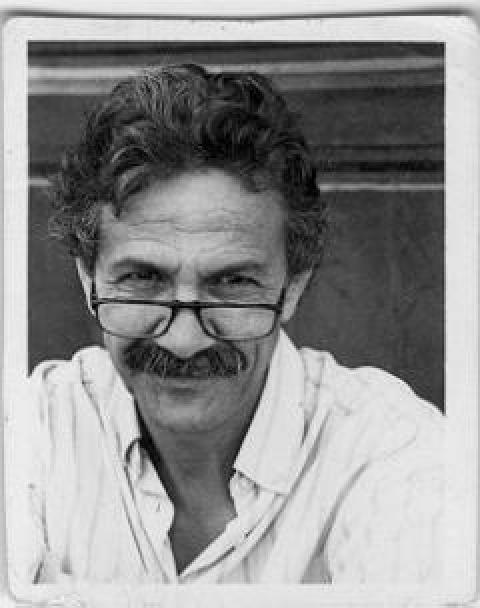

December 3, 2014 marks the 20th anniversary of the assassination of Algerian journalist. He was shot while eating in a restaurant near his Algiers office and died the next morning. That same morning Mekbel had published an article in his paper Le Matin that would prove to be his own eulogy. Its raw words memorialize journalists everywhere who are targeted for practicing their profession. The piece, known as "Ce voleur qui" or "This Thief Who.," which describes the plight of press workers trapped in conflict, remains sadly topical today. It recalls not only Mekbel's murder, but also those of Iraqi journalists Raad Mohamed al-Azzawi and Mohanad al-Akidi, and Americans Steven Sotloff and James Foley, all of whom have been killed by "Islamic State" this year.

Throughout the 1990s, Algerian journalists were extra-judicially condemned to death and executed by the country's murderous armed fundamentalist groups, while simultaneously facing endless restrictions and harassment by the military-backed government. Journalist and editor Lazhari Labter analyzed the killings in his profession as follows: "the fundamentalist terrorists implemented a systematic program of liquidation of members of the journalistic family - a program summed up in the sinister slogan of the Armed Islamic Group: `Those who combat us with the pen will die by the sword.'"

The Algerian writer Tahar Djaout - one of Algeria's first intellectuals cut down in the 90s - had expressed the reporters' predicament perfectly: "If you speak out, they will kill you. If you keep silent, they will kill you. So speak out, and die." Mekbel did just that. The nineties violence which claimed his life made Algeria, according to a 2012 United Nations report, one of the five deadliest locations for reporters in the last twenty years. A total of a hundred press workers, including sixty journalists, were killed by the fundamentalist armed groups between 1993 and 1997, a terrible history chronicled by Ahmed Ancer, a journalist with the paper El Watan (the Nation), in a book appropriately entitled Encre Rouge (Red Ink).

This violence was, as the UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions described the murder of journalists, "the most extreme form of censorship. . . ." The journalists' counter-attack was to survive, to keep writing no matter what. After Saïd Mekbel was killed, Le Matin reprinted his articles over many days "to spite the killers."

In life, Saïd Mekbel was an honest and humorous socio-politial critic who frequently took aim both at politicians in the Algerian government as well as at the fundamentalist armed groups that battled them. His son Nazim Mekbel, president and co-founder of Ajouad ("the generous") Algérie Mémoires, a collective of families of victims of the 1990s fundamentalist terrorism, wrote last December on the 19th anniversary of the killing about some of his father's most pointed criticisms. "o the Sheikh of the FIS (Islamic Salvation Front), who advised that we should prepare to change our modes of dress and eating, he replied.. `I encourage you, in all fraternity, to go. reclothe yourselves.'"

As Nazim recalled, his father had also written of torture - which like fundamentalist violence was endemic in 1990s Algeria. "olice officers should be given ashtrays with the explanation that they are to be offered to some of their colleagues. who in certain police stations, ask detainees to open their mouths so as to serve as ashtrays."

Of Algeria's terrible wave of 90s political assassinations, Saïd Mekbel had noted that, "They are done so as to suit all the political extremes that want to gain or keep Power." He asked a question that is still globally relevant. "Is there really nothing else that can be unrolled on the road that leads to the throne other than this macabre carpet made of the bodies of intellectuals?" Nazim recalled that his father wondered in print who exactly would kill him, remarking that "sometimes I long to meet those assassins and especially their commanders." This was because, as he explained, "I want to know who will order my death."

Of his country's youth, Saïd Mekbel had worried about "what sort of mutants" were being produced - "traffickers in arms and in drugs, economic con men and con men of religion." According to Nazim, for his father, "a prime example of the intolerance which plagued his country was the letter he received from an `anonymous combatant' who promised an Islamic Algeria while condemning another reader `who had the cowardice to sign his name and to affirm that he was a Christian Algerian, proud of his identity and living his faith, his convictions and his ideas.' " Mekbel was horrified by the violence such ideas produced. After the assassination of two Spanish nuns by the Armed Islamic Group in Algiers in 1994, he posed a question which still needs answering in the era of the so-called Islamic State: "Toward what world of darkness are we headed, we who dream only of light?"

While Pope Francis today asks people of Muslim heritage to condemn terrorism, Mekbel was already doing so twenty years ago. His February 1994 open letter to the terrorists of Algeria distills the rage of many people in Muslim majority societies against those who butcher in the name of Allah. "Tell me, partisan of terrorism . . . you who regularly . . . explain that terrorist acts are done . . . to-I quote-`bring down the military junta in power,' tell me how assassinating a schoolteacher in front of . . . the children in his class, when he only had a little piece of chalk in his hands, tell me . . . how this ignoble execution contributes to `bringing down the military junta.' "

Ten months later, on December 3, 1994, the man who had the courage to ask this question in print was himself fatally shot. Saïd Mekbel's assassination was claimed by the Armed Islamic Group. To date, no one has been brought to justice for this crime, and as insisted by Mustapha Benfodil, who is currently writing about Mekbel for the Algerian newspaper El Watan, some form of accountability for these 1990s atrocities remains essential.

Amongst his father's 1300 columns from that period, Nazim Mekbel selected a particularly defiant one that should be remembered on this somber anniversary. It appeared in November 1991 when the still ascendant Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) threatened to use the ballot box to reduce Algeria to an "Islamic State." Entitled "Ya FIS" or "O FIS" (the acronym also means "son" in French), the piece is a sardonic reply to correspondence from a fundamentalist sympathizer. "A big thank you for your letter. I found it very nice, even if at the end of each sentence you promised me that I will do many things lying face downwards when the FIS comes to power. Your letter really put me in a good mood. I was able to laugh at treasures like this one: `Lying face downwards, you will fall from on high, Saïd, when you learn the results of the election of December 26, 1991.'" Mekbel signed his open letter with insubordinate courtesy. "Take care of yourself, ya FIS.

I greet you, but not face downwards."

Lazhari Labter wrote recently from Algiers to say that "all his life Saïd Mekbel fought for FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, for DEMOCRACY, for HUMAN RIGHTS and WOMEN'S RIGHTS, for LIBERTY." Summing up his own body of work, Saïd Mekbel observed that, "ruth is like justice. It needs witnesses.. Even very small witnesses who can simply write things that will last." While he has been gone for exactly twenty years, his words - written against extremism, terror, abuse and corruption and yet infused with humor wherever possible - will never die. In honour of both uncomfortable truths and illusive justice, this great Algerian witness wrote things that will indeed last.

Here is a translation of his final column.

This thief who.

This thief who, in the night, keeps a low profile when going home, it is he.

This father who recommends that his children not say in public what his miserable line of work is, it is he.

This bad citizen who skulks in the courts, waiting to appear before judges, it is he.

This individual picked up in a roundup and propelled by a riffle butt into the back of a truck, it is he.

It is he who leaves his house in the morning without being sure he will arrive at work.

And it is he who leaves work again at night, with no certainty of reaching home.

This vagabond who no longer knows where to spend the night, it is he.

He is the one who is threatened in the secrecy of an official's office, the witness who must swallow what he knows, this naked and helpless citizen..

This man who makes a wish not to die by having his throat cut, it is he.

This body onto which they sew back a decapitated head, it is he.

It is he who does not know what to do with his hands, apart from scribbling his humble writings, he who hopes against hope, because roses grow well - don't they - on a pile of manure.

He who is all of this and who is only a journalist.

Translated by Karima Bennoune

[Karima Bennoune is a Professor of Law at the University of California, Davis School of Law, and former Amnesty International Legal Advisor. Her book, Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here: Untold Stories from the Fight Against Muslim Fundamentalism, won the 2014 Dayton Literary Peace Prize. Karima recently gave the TED Talk: When people of Muslim heritage challenge fundamentalism.]

Many thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word