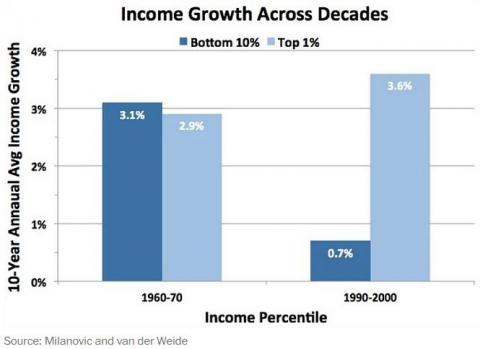

Once upon a time, prosperity was so broadly shared that the bottom actually grew faster than the top. It was called "the 1960s."

You can see what this looked like in the chart above, taken from data in this paper by Roy van der Weide and Branko Milanovic. It shows how much the bottom 10 and top 1 percent grew, adjusted for inflation, in both the 1960s, 1990s and 2000s. It seems almost impossible now, but the income of the poorest households -- the bottom 10 percent of them -- grew the fastest in JFK-era America, with the top 1 percent a little bit behind.

But since then, the economy has undergone a fundamental shift. Globalization has forced the working class to compete with cheap labor overseas. And technology has turned what used to be good-paying jobs into redundant ones — while letting superstars reach more people and earn more money. But most disheartening is that, more often than not, policy has made all this worse. Whether it's tax cuts for the rich, financial deregulation, or deunionization, the government has heaped the most help on the only people who are still doing well.

The result, as you can see in a little more detail below, is a world where income growth has collapsed for the bottom 80 percent, but reached new highs for the top 1 percent. And the 1990s, remember, were the good times for the middle class. Unemployment was as low as it's been in living memory, wage growth was, relatively-speaking, high, and the stock market was making everyone feel rich.

Source: MIlanovic and van der Weide

In the 2000s, wage growth was negative for a lot of people. The 1 percent slid a bit because of massive stock market losses in the 2008 financial crisis, but if the data were updated through 2014, they'd surely be booming again. The top 1 percent, after all, have gobbled up 95 percent of the recovery.

This is the economic problem that's become a political one for both parties.

Republican reformers have finally stopped assuming that growth will trickle down, because it hasn't, and started talking about wage subsidies instead. But the problem, as Jonathan Chait points out, is that Republicans only seem to support low-income tax credits in theory when they don't actually cost any money. Paul Ryan, for example, said he supports expanding the earned-income tax credit for childless workers, but at the same time wants to let the already-expanded EITC expire for married couples and families with three or more kids*. Democrats, meanwhile, have some pieces of what could be a middle-class agenda — taxing the rich to spend on the rest, raising the minimum wage, and universal pre-K — but it's tilted more towards the bottom than, say, someone making $50,000.

Policymakers, in other words, have to figure out how to turn economic growth into wage growth for the bottom 90 percent. Otherwise the American Dream will just turn into another fairy tale.

*Correction: This post has been updated to make clear that Ryan still supports expanding the EITC for childless workers, but does not support continuing the expanded EITC for married couples or big families.

Matt O'Brien is a reporter for Wonkblog covering economic affairs. He was previously a senior associate editor at The Atlantic.

Spread the word