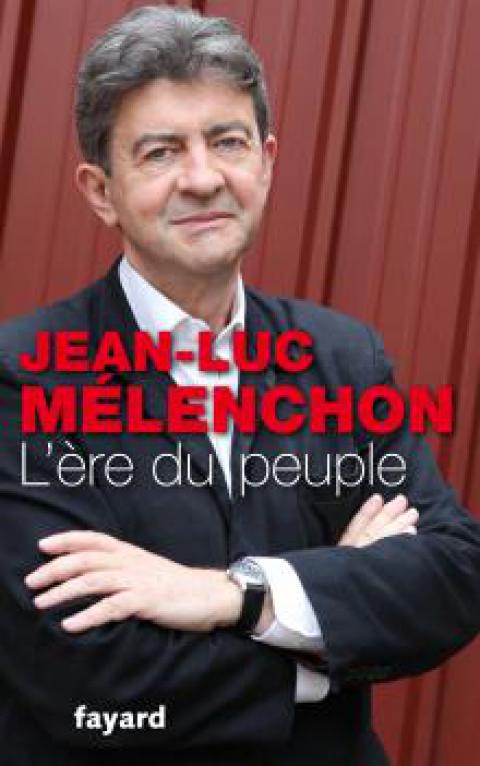

December 10, 2014 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal -- In October, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s new book, The Era of the People (L’Ére du Peuple) was published. In it Mélenchon, until earlier this year the co-director of France’s Left Party (Parti de Gauche) and the 2012 presidential candidate for the Left Front (Front de Gauche), outlines “a theory of the citizens’ revolution” and the rationale for his new political project the Movement for the 6th Republic.

The relatively short tome (just under 150 pages) assembles sociological and cultural analysis, and reflections on geopolitical, economic and environmental themes in order to put the case that “the people” are the new social agent for the fundamental social change necessitated by the growing ecological crisis.

The Movement for the Sixth Republic (or M6R) is gaining support within France, with more than 70,000 now signed on to its online statement, including numerous public and political figures. Recent support from dissident Socialist Party members and Green Party members has broadened its support and legitimacy. On December 10, the new online social network was launched, which provides space for citizens to discuss, debate, propose ideas and actions, and organise themselves at a local level.

The campaign feeds into the heart of an ongoing debate in French politics that has threatened to destabilise the main political force to the left of the governing Socialist Party, the Left Front – a coalition of the Communist Party, the Left Party and other left forces. The debate initially centred on whether or not to form alliances with Socialist Party members during local elections, but now has become a fully fledged debate about the status of the established left and the strategy for anti-capitalist struggle and staving off the rise of the far right in France.

‘The left can die’

The first chapter is titled “The left can die”, ironically quoting Prime Minister Manuel Valls, and it opens with the provocation: “Here is the first political fact with which we must work: there no longer exists any global political force in the face of the invisible party of globalised finance.” The old left of social democracy is dead, welcome to the era of the people.

The general attack on social democracy quickly becomes a sharp critique of the ruling Socialist Party in France, with Mélenchon denouncing current president François Hollande for being worse than his right-wing predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy. Mélenchon spends some time apologising for his support for Hollande in the second round of the presidential elections in 2012, saying, “I would have never believed that he would betray his electors so quickly, so massively, so totally.”

Mélenchon savages Hollande, outlining a huge list of the president’s crimes, from immediately backing down on his promise to renegotiate the fiscal pact, to giving 40 billion euros to the CAC 40 (a French stock index), to allowing joblessness and homelessness to rise, increasing the pension age, blocking Bolivia’s President Evo Morales from French airspace at the behest of the US government, his support for Benjamin Netanyahou when Israel was committing war crimes in Gaza. Despite positioning himself, during his presidential campaign, as “an enemy of finance” Hollande has been one of the most active leaders in Europe opposing a tax on financial transactions.

In fact, for Mélenchon all these failures represent the Socialist Party finally becoming a “normal” social-democratic party in the 21st century: in full retreat from its founding principles. The Socialist Party is now a far cry from the Lionel Jospin government of the late 1990s (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lionel_Jospin) that introduced the 35-hour working week with no loss of pay, and is like any other bankrupt social-democratic party in Europe. With Hollande’s popularity sinking to 12% it’s not hard to imagine a future in which the Socialist Party goes the way of other social-democratic parties such as Greece’s PASOK, which has all but disappeared from the political stage.

According to Mélenchon, Hollande’s presidency has “led the 5th Republic to the limits of all its technocratic and authoritarian defects. Right up to the point of opening up the latent crisis of the regime.” Hollande has been a deeply undemocratic president, sacking his cabinet twice and avoiding consultation with civil society and trade unions. “In short, the impunity of the president’s caprices push him towards the permanent abuse of power.”

With the Socialist Party turning so far right, Mélenchon admits that the sentiment of “left or right, they are the same” has become so prevalent among the French public that one must leave the “left” in order to reach the people themselves. When the language of the left is taken by Hollande and Valls and used against itself, “how can one think correctly? How can one think at all?”

Intellectually, the official “left” is in an overextended coma. None of the advancing realities of the world have a place in its argumentation, nor in its projects, supposing that it had any. But above all, it is already dead in thousands of hearts. The sickness is quite advanced. It will not be repaired with knowing explanations of how to discern the true left from the false.

Yet it is not only because social democracy has given up its own program that the language of left and right is no longer viable. Mélenchon unequivocally states that social democracy is dead not just because it isn’t carrying out its own program, but because it has no solution to the fact that capitalism now threatens the stability of the biosphere.

Social democracy doesn’t respect its own programme? Instead it is relentless in applying that which it pretends to fight against? That changes nothing. Even if it returns, it will be obsolete and dangerous.

It is time for a new approach.

For Mélenchon, this book marks his break with traditional leftist thinking. He notes two decisive factors contributing to this break: first, an engagement with ecological politics, and second through serious study of the revolutions of Latin America, the Arab Spring and the “citizens’ tide” in Spain. In essence the book attempts to keep the entire principles of leftist thought (historical materialism, anti-capitalism, universalism, republicanism) but to think them anew outside of what Mélenchon sees as a dead-end of the left.

The anthropocene and the era of the people

If the book takes the era of the people as its title, it is the anthropocene that is its starting point. For Mélenchon, the 20th century has seen one profound change above all others: the explosion of the number of human beings on the planet. The increased use of resources means that humanity has now become a fundamental player in the life of the biosphere. This represents a “total change of trajectory of the history of humanity. A veritable bifurcation.”

Mélenchon remarks that at the middle of the 20th century, there were 2.5 billion people on the Earth. Now there are over 7 billion. He notes that it took more than 200,000 years for humans to reach the first billion, and yet the most recent billion added took but five years, between 2009 and 2014.

Such a growth in human population changes not only the relationship to the environment, but social and political relations as well:

The number of human beings is not solely a quantity. It is a decisive factor of their common life. And also of the perceptions that they have of themselves. In this sense, human history is first of all that of the number of individuals that compose it.

So rather than a mere effect of economic growth, population growth is for Mélenchon one of the drivers of fundamental economic, ecological and political changes.

Yet while Mélenchon gives such a crucial place to the growth in the human population, coming close to a Malthusian position that is roundly critiqued by ecosocialist thinkers, he argues neither that capitalist growth is the direct result of population growth, nor that the solution to the ecological crisis is the reduction of the population. For him the growth in the human population is not a problem in itself, but only a problem under the irrational system of capitalism. In fact, Mélenchon argues the opposite: this massive number represents an opportunity. So, while “in the current conditions of production and consumption we would need several planets in order to respond to the needs if everyone lived as we [in the developed West] do”, nonetheless “changing our view of the world begins by deciding to see this number and its rhythms as the subject of history”.

In a similar way to Naomi Klein’s recent This Changes Everything, it is a fundamental argument of the book that the “era of the people” has arrived due to this contradictory fact: we have become so numerous and developed that we threaten the stability of the very ecosystem that gives us life – and yet we are the sole actors who can stop this from taking place.

In addition to a brief but sober outline of the coming disasters caused by climate change, Mélenchon makes a particular focus of the oceans. He notes that the declining resources on land are leading companies to explore more and more the vast reserves of hydrocarbons and mineral resources under the sea. He reasons that, “the sea is truly the new frontier for humanity”, adding that, “Whatever it is, humanity’s entrance into the sea has commenced. Without debate, without plan, without precaution.” Added to this the already declining health of our oceans due to agricultural and industrial pollution is the massive growth of maritime traffic, overfishing, carbon dioxide and acidification.

Mélenchon argues that France has a particular duty to begin fighting for regulation of our treatment of the oceans, since it has the second largest marine territory in the world (after the US), 16 times its land territory. Yet, the Hollande government has done practically nothing on this front, in fact, worse than nothing: it cut 5% of the budget for the oceans in 2013 and another 2% in 2014, with more cuts likely to follow.

The oceans are critical in another respect: rising sea levels are set to displace more than 200 million people by the end of the century, in what will be an unprecedented global social crisis. With more than 75% of the Earth’s population living within 100 kilometres of a coast, hurricanes and super storms will also provoke massive crises that our under-resourced social services will not be able to deal with.

Mélenchon argues that the scale of the environmental crisis and social crises associated with it raise the necessity of economic planning and public ownership. He conceives of an “environmental republicanism” in which all people are engaged in the commitment to the public good and environmental sustainability, and in which protagonist democracy would play a fundamental role. He flatly rejects the idea of a “green capitalism”, calling “absurd” the idea of attempting to “reconcile the market economy with the management of the changes in the global ecosystem”.

He also makes clear that the massive wealth located in the financial sphere of the economy represents precisely the resources that need to be taken over in order to bring about the ecological transition of the economy.

Another issue that Mélenchon raises is that of the “ecological debt”. He cleverly points out that while humanity has an enormous ecological debt to pay the planet (from overdrawing more resources than the Earth can replenish), mainstream politicians in Europe are instead concerned only with the public debt “crisis”.

To deal with the real crisis, that of the environment, Mélenchon proposes “the Green Rule” in which “no production or activity can withdraw more than what nature can replenish”. He believes that the implementation of this law, rather than inhibiting human creativity and freedom, would unleash a major force of human creativity and ingenuity from engineers and workers in how to reduce waste, increase the lifespan of goods, recyclability, and so on. Such a green rule will “oblige us to invent the revival of human civilization. And the concrete refounding of the progressivist project in history.”

As a testament to how seriously Mélenchon takes ecological politics, the book concludes with the first four theses from the Ecosocialist Manifesto [http://ecosocialismedotcom1.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/eco-socialism-f…] that was co-written in December 2012 by a large number of environmental and socialist activists and thinkers, including Mélenchon.

The new gravediggers: From the working class to the people

The Era of The People is full of interesting commentary on the nature of modern life, ranging from reflections on the decline of the US empire and the instability that comes with it, outlining a theory of ecological and “solidarian” protectionism, to a critique of the theory of a “shock of civilisations” between East and West, to an analysis of the shortening and impoverishment of human experience of time in the neoliberal information age. Yet, if the anthropocene and the environmental crisis provide the general framework of the book, its key concern is the strategy for meeting this historic challenge.

For those on the left, perhaps the most contentious argument of the book will be the assertion that “it is the people who take the place that yesterday was occupied by the ‘revolutionary working class’ in the left-wing project.”

Mélenchon is unequivocal:

The people will lead [the new rallying cry] and not a particular class directing the rest of the population. The people, those urbanized human swarms that form the essential part of the contemporary population.

Mélenchon argues that it has largely been struggles outside of the traditional organised working class that have led the revolutions in Latin America and in North Africa. He suggests that “the workplace is no longer the central site where a global political consciousness is expressed.” He goes on:

Under the status of precarity, in both big businesses and small, with a unionization continually beaten down and criminalized, threatened constantly by collective layoffs … the workers live under the pressure of unemployment en masse, of delocalisation and obsolescence of productions.

“The people” do not become this agent because of any particular desire that they do so, but take this position in modern capitalism because of objective trends in the system itself. In this sense they take over the role of the “gravediggers” of the system previously allotted to the industrial proletariat in orthodox Marxism. In the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels famously wrote:

The advance of industry, whose involuntary promoter is the bourgeoisie, replaces the isolation of the labourers, due to competition, by the revolutionary combination, due to association. The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. (Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto, chapter 1.)

In a similar process, Mélenchon suggests that the modern city – a necessary element of capitalist development – has gathered together an unprecedentedly vast number of people, creating a new gravedigger. In the last 50 years the percentage of the world’s population living in cities has risen from 20% to 60%. While they aren’t organised in the same way as the industrial proletariat, there are two factors that cut across both their social isolation (which has only intensified with the growth of cities) and their ideologically enforced individualism:

- The first of these is their sharing of common needs, made necessary by life in the city. These include public transport, health care, education, rent prices, employment, access to networks, and so on. These form a spontaneous bond that links all city dwellers. Mélenchon points out that it was demands around these issues, which have been the triggers of the recent revolutions in Latin America and North Africa.

- The other factor that brings the people together is the explosive growth of social networks. Mélenchon notes with excitement that around 2 billion people are today connected through social media. This allows for the rapid sharing of information and organisation of action as has been seen in Spain and in the Arab Spring.

Such is the essential political result of the number [of people]. By creating endless urban concentrations, it has gathered immense populations and amalgamated them by similar needs that can become common demands. From there, the endless city creates the opportunity of a collective conscience and sketches out its program.

From the individual to the citizen

If the people as a “multitude” of individuals represent the new social agent-in-potential, they begin to realise this potential when they become “citizens”.

This term is not to be understood in any sense that would exclude undocumented workers, for instance. The people for Mélenchon are comprised of the unemployed, women, students, migrants, precarious workers, racial minorities, the retired, as well as white- and blue-collar workers, and so on. Becoming a “citizen” is also not a matter of individuals gaining a feeling of responsibility towards the system that keeps them down.

Instead, citizens are people insofar as they are organising themselves to change society from the ground up. For Mélenchon “the people” are only visible when they are taking action. The most important aspect of the action of the people according to Mélenchon is that of the “general” or “citizens’ assembly” as practiced by the Indignados in Spain, and the Occupy movement elsewhere. This practice of claiming a space within the city and beginning to institute its own laws Mélenchon calls “sovereignty”.

Sovereignty is the political motor of society as well as its link.

Mélenchon asserts:

My thesis is: the unformed multitude becomes the people by seeking to secure its sovereignty in the space that it occupies.

Mélenchon argues that this process should ultimately take the form of a constituent assembly where “by defining the Constitution, the people identify themselves with their own eyes”. And further:

They constitute themselves in a way. For example by saying which rights are theirs, by organizing the way to make decisions, by defining the group of authorities that will act to make the decisions function.

Mélenchon notes that abstention is on the increase and depoliticisation is high, highlighting the need for a radically new democratic system founded on this idea of sovereignty.

For this emphasis on the people, Mélenchon has been consistently accused by left and right of “populism”. In the book, he responds to such a criticism with a biting attack:

When one sees those who are obsessed with accusing people of “populism” as a form of insult without being able to define its content, one hears the voice of the well-to-do suburbs who mistrust the disreputable adjacent streets. The hatred of populism is nothing other than an avatar for the fear of the people.

The argument could be made that “the people” represent nothing more than “the working class” conceived more broadly, united by its lack of ownership and control of capital more than by its role in creating surplus value. The difference is symbolic, but no less important for that: Mélenchon is attempting to reach masses of ordinary people who, for a host of historical reasons, do not find themselves able to identify with the label “working class”. “The people” is an inclusive term that is defined by what it is not: the political caste and the financial oligarchy. Or more simply:

Our epoch is that of the struggle of the people against the oligarchy.

This is not to say that there isn’t any role for the traditionally conceived working class. Workers will still make a crucial contribution to the overall struggle through struggles for wages and conditions on the job, through their ability to take over planning of industries, and through the creation of co-operatives that show alternative modes of production. But fundamentally, the role of the workers “decreases in the workplace, only to increase in the heart of the people”, by joining them in common struggle on the street.

Equally, the “citizens’ revolution” replaces and incorporates the old “socialist” revolution:

The citizen’s revolution is not the old socialist revolution. Certainly, it includes the tasks that the latter aimed at: the struggle for equality of wellbeing, collective ownership of common goods, universal education, and so on. But the citizens’ revolution aims at broader objectives. Those of the general human interest. Its programme starts with the evaluation of the relationship with the ecosystem and with the tasks that follow from it. It is called “citizen’s” because it designates the actor accomplishes it and which must remain its master: the citizen.

Mélenchon outlines the three major facets of this revolution: a fundamental change in property relations in favour of common ownership, the overturn of the legal order in favour of the people and the environment, and finally, re-establishing the institutional order in favour of real democracy and decentralisation.

M6R: Spontaneity and organisation

One area that appears lacking in the book is the question of strategy beyond this constituent assembly process.

Where a constituent assembly process has taken place in Latin America it has tended to be led by a party that has won popular hegemony. Likewise in Spain, where a similar process could well unfold in the next few years, it will most likely be Podemos that leads the charge. Such processes also come on the back of massive upheavals and huge and consistent spontaneous mobilisations of people, such as have not yet been seen in France. Can Mélenchon’s M6R kickstart such mobilisations, or begin a deep-rooted citizens’ movement that could bring hundreds of thousands onto the streets?

The potential criticism that the M6R puts the cart before the horse, creating a network that could (or should) only really emerge “organically” from such mass protests misses the fact that such a network is never purely “spontaneous” but is always a decision by a particular actor in the movements. For the left to wait for such a network to emerge before engaging with it is an excuse for avoiding giving leadership. While Mélenchon’s strategy is risky, equally risky is the left getting stuck in old formulas, in a context where the far right is taking initiatives and winning the hearts and minds of some ordinary people in France.

Looking further down the track, Mélenchon would hardly agree with a strategy of “changing the world without taking power”, yet he defines no particular way the people might take do so. Does Mélenchon see a new party emerging out of the M6R? He has made numerous statements about how the 2017 presidential elections will be an “insurrection at the ballot box” for the 6th Republic. Will the M6R contest elections or feed into a particular candidate’s campaign?

Perhaps these questions are not answered in the book for a reason: that such specifics will unfold differently and unpredictably in different countries, and that, ultimately, it is up to the people in France to decide as they organise themselves through the M6R. For the time being the task of the M6R is to create a vast network of people united in their opposition to the “oligarchy” and in favour of a new, more just and ecological French Republic.

The Era of the People provides a strong rationale for this project, and a provocative and worthwhile contribution to global discussions around strategy for social change in the 21st century.

[Liam Flenady is a member of the Australian Socialist Alliance presently resident in Europe.]

Spread the word