The FBI’s system for tracking fatal police shootings is a “travesty,” and the agency will replace it by 2017, dramatically expanding the information it gathers on violent police encounters in the United States, a senior FBI official said Tuesday.

The new effort will go beyond tracking fatal shootings and, for the first time, track any incident in which an officer causes serious injury or death to civilians, including through the use of stun guns, pepper spray and even fists and feet.

“We are responding to a real human outcry,” said Stephen L. Morris, assistant director of the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, which oversees the data collection. “People want to know what police are doing, and they want to know why they are using force. It always fell to the bottom before. It is now the highest priority.”

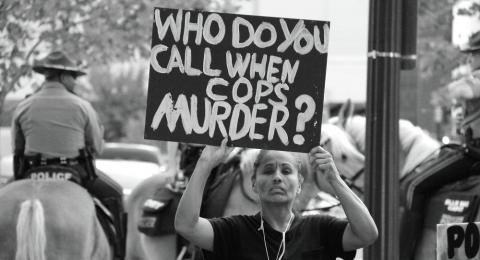

The FBI’s efforts follow a year of national focus on fatalities and injuries at the hands of police, with widespread frustration over the lack of reliable data on the incidents.

Morris said the data will also be “much more granular” than in the past and will probably include the gender and race of officers and suspects involved in these encounters, the level of threat or danger the officer faced, and the types of weapons wielded by either party.

The data also will be collected and shared with the public in “near real-time,” as the incidents occur, Morris said, instead of being tallied in aggregate at the end of each year.

David Klinger, a former police officer and professor at the University of Missouri at St. Louis, who has advocated for better data for more than a decade, said he was pleased to hear of the new system but skeptical about its implementation.

“The devil is in the details,” Klinger said. “When agents of the state put bullets downrange in citizens, we need to know about that. In a representative democracy, we need to know about that. We are citizens, not subjects. We also need to understand the circumstances of the shootings, so we spot trends, so we can improve training.”

Getting reliable data on fatal police encounters in the United States is notoriously difficult. The FBI has struggled to gather the most basic data, relying on local police departments to voluntarily share information about officer-involved shootings. Since 2011, less than 3 percent of the nation’s 18,000 state and local police agencies have done so.

After the 2014 shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown unleashed a wave of nationwide protests, activists, media organizations and some law enforcement leaders began clamoring for a more accurate count. In January, The Washington Post began to build a database of fatal police shootings. In addition to recording each shooting, Post researchers gathered more than a dozen details about each case, including the age and race of the victim, whether and how the person was armed, and the circumstances that led to the encounter with police.

As a result, the public could see information about fatal police shootings in unprecedented detail. As of Tuesday, The Post had identified more than 900 fatal shootings by police — an average of nearly three deaths a day. By contrast, the FBI has recorded about 400 deaths a year over the past decade, or just over one death a day — less than half the rate recorded by The Post.

Shortly after The Post announced its project in May, the Guardian newspaper unveiled a similar database that seeks to track all deaths in police custody, whether by shooting or other means.

In October, FBI Director James B. Comey acknowledged the stark disparity between The Post and Guardian databases and the FBI’s own efforts. At a private gathering in Washington of more than 100 politicians and law enforcement officials, Comey called it “unacceptable” and “embarrassing and ridiculous.”

Last week, a 35-member advisory board made up of police chiefs and representatives of police organizations from across the country gave the green light to the new FBI data-collection effort. The proposal goes next to the FBI’s legal offices for review and then to Comey for his signature.

A working group is also being formed to determine what data should be collected, Morris said; its proposal is due to the advisory board in June.

The new database will continue to rely on the voluntary reports of local police departments; FBI officials said they lack the legal authority to mandate reporting.

But Morris said the leaders of the nation’s largest police organizations have agreed for the first time to lobby local departments to produce the data. The Justice Department is also looking to offer federal grants to local departments that may need additional resources to comply.

“We will be relying on peer pressure and financial incentives,” Morris said.

Fairfax County Police Chief Edwin C. Roessler Jr., a member of the advisory board, said police organizations “will be taking a leadership role to use peer pressure to get all departments to report on this.”

“Everyone has the right to know the details of these events,” he said.

Morris is also trying to make it easier for local police to submit the data. He has technical experts working on a simple electronic form — “something like a Turbo Tax form,” Morris said.

The data “can be used by academics and departments to create better policies and training,” Morris said, adding: “Our end goal here is to save lives.”

Change is also underway at the Bureau of Justice Statistics, another Justice Department agency that has kept a separate count of civilians who die in police custody.

The bureau scrapped its old database and this year created a pilot program that relies on The Post’s database and other open-source data-collection efforts to identify deaths that are not being reported. Then, BJS officials contacted police, medical examiners and other local officials to check the accuracy of the information and to gather additional facts.

The bureau plans to convert the pilot into a full-fledged program in the spring and produce its first full year of data by the end of 2016.

“We needed to start over,” said Michael Planty, who oversees the database for the bureau. The old data, he said, was “unreliable.”

Kimberly Kindy is a national investigative reporter at The Washington Post.

Spread the word