Territorial integrity and preservation of existing borders have always seemed essential preconditions for any international resolution over Syria. Diplomatic efforts were made to foster a dialogue among the parties; a feeble military coalition was formed to “degrade and destroy” Daesh; while military advisors were sent on the ground to simultaneously assist “moderate rebels”, Kurdish Peshmerga and a crumbling Iraqi Army.

However fanciful such a strategy may appear, it is safe to say that these operations were all supposed to work in the same framework: maintain existing borders, facilitate a political transition in Syria and fully restore Damascus and Baghdad’s territorial sovereignty.

What the last weeks suggest is rather a trend reversal. Diplomats, analysts and generals from various political environments have indeed started toying with the idea that remapping the region along ethnic lines might be the key for a conflict resolution. In other words, the possibility of partitioning Syria and Iraq into minor ethnic states has become a more tangible option. The proposal never came out coherently, but started fluttering on media commentaries; and as some observers noticed, it was circulating in the corridors of the last Vienna Talks. Reality is that a border reshuffling in ‘Syraq’ would probably meet positive consideration in more than one capital city, from Jerusalem to Tehran.

It would grant the Kurds with a nation. It would safeguard Moscow’s sole port on the Mediterranean, keeping an Alawite state with Latakia as capital city and Tartus as Russian military garrison. It could be accepted by Riyadh, as it’d entail a Sunni state stretching from Damascus to Baghdad, including part of the territories currently under Daesh’s control. It’d be also welcomed in Tehran, taking southern Iraq – and the holy Shiite sites of Karbala and Najaf – in the Islamic Republic’s arms. And, not surprisingly, it would not be disdained in Jerusalem either. In a country that already offers a doubtful example of how citizenship, religion and ethnicity can intertwine with one another. Overall, the hypothesis of partitioning ‘Syraq’ into minor ethnic states has been forging ever forward; so much so that even the UN and Arab League Envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, had previously defined such a scenario as dramatic but possible.

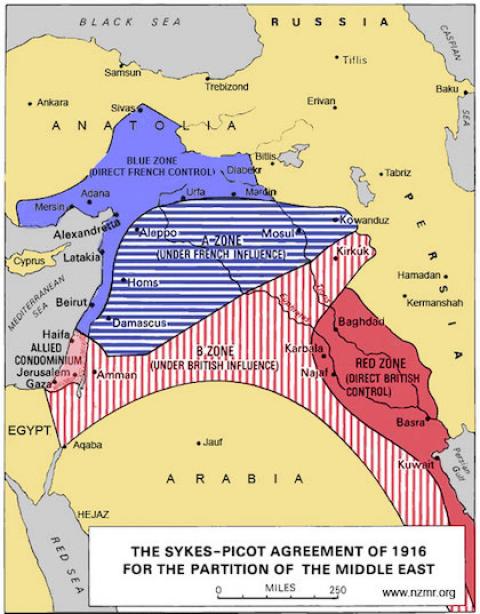

Those supporting the ‘partition-thesis’ tie their argument to the idea that borders in the Middle East were drew as lines in the sand by the Sykes-Picot Agreement; through which Britain and France divided up the Ottoman Empire into four proto-nation states. The secret pact - signed by the British diplomat Mark Sykes and his French counterpart George François Picot in 1916 – partitioned in fact the empire’s eastern territories into minor areas of influence, where Paris and London would have exerted their Mandate. Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Transjordan, which had never existed as state entities, firstly emerged from that division.

What is increasingly argued in some political environments is that the failure of Iraq and Syria as nation states results from that pact’s unfounded nature; while the re-emergence of transnational loyalties – as sectarianism – from Beirut to the Iranian border should actually suggest a radical map revision. Alawites, Shi’as, Sunnis, Druzes and Kurds are hence portrayed on detailed thematic maps as corresponding to homogeneous regions, while gentler frontiers are drew as if they were more respective of cultural diversity than current off road borders. The implicit assumption is hence that ethnic divisions have always been there; that we simply didn’t want to acknowledge them; and that turning such transnational loyalties into citizenship in all respects would be key to a crisis’ resolution. I wonder if reality is a bit trickier.

A first attempt to constitute an ethnic state in the region was made by the French Mandate in Lebanon, where Paris wanted to establish a Christian nation as Western outpost in the ‘Muslim world’. The plot didn’t succeed, but it certainly had major responsibilities for the Lebanese state’s future fragility: Lebanese Christians and Muslims – regardless of their sect – fought each other between 1975 and 1989; and Beirut remained divided into a Christian East and a Muslim West for at least two decades. However, history moved forward, and as the recent jihadist attacks in (predominantly Shiite) South Beirut show, the Lebanese state is now struggling to keep together Sunnis and Shi’as; not Muslims and Christians. This obviously doesn’t mean that violence in the region is more likely to be produced by a perennial clash within Islam, but that religion, as ethnicity and sect, is necessarily subjected to political modification and people’s emotions.

Lebanon is particular, but not unique; and if we look for instance at the Iraqi history we should reach analogous conclusions. The country - now used as a proof for the partition-thesis - has been almost extraneous to sectarian strife until the war against Iran (1980), when the confrontation with a Shi’a state – namely the Islamic Republic – provoked the alienation of the Shiite communities in southern Iraq. Until that time, the Pan-Arabist discourse of the Ba’ath had been as ethnocentric as laity; and sectarianism had rarely represented an issue for the country’s stability.

Finally, and taking a step back to Syria, Assad’s dynasty certainly didn’t champion human rights and democracy, but it was particularly successful in creating a cross-confessional social pact. This doesn’t mean that he didn’t take advantage from sectarian cleavages for crafting political coalitions, but that Syrian national history isn’t necessarily one of inter-ethnic conflict. The cross-confessional fashion of the 2011 uprisings - extensively praised on western media - should at least suggest so.

To sum up, contrary to what a larger and larger bunch of ‘experts’ is trying to argue, it would be highly misleading to believe that Syrians and Iraqis have always been inclined to kill each other for ethnic reasons.

Both Syria and Iraq have gone through their own national history; a history of military coups, authoritarian regimes and foreign encroachments, certainly, but not deserving for this reason to be erased with a simple map revision. Moreover, ethnic states have never featured in the region, where the Caliphate and the Ottoman Empire constituted the only two political realities before 1916. Here, the devious and groundless character of the Sykes-Picot Agreement is certainly clear for anyone to see; but is a Balkanisation of the Middle East really the way forward?

In creating such a precedent, how will it then be possible to avert sectarian strife in Lebanon - a country constantly on the brink, which shares with Syria porous borders and analogous ethnic composition? How will be avoided Libya’s breakdown into a myriad of tribal states? Which political solution can we hope for in Yemen? And finally, how will we be able to create multicultural societies in Europe, when we encourage ethnic segregation in the same countries where migrants escape from? Pandering every voice calling for fragmentation will only exacerbate parochialism and communal hatred. A peaceful resolution for the Syrian crisis has to pass by the Syrian state, maintaining continuity with history and not reinventing it.

[Giovanni Pagani has an MSc in Middle East Politics from the London School of Oriental and African Studies. He wrote his dissertation on urban reconstruction and sectarian fragmentation in post-war Beirut. He is currently collaborating with the Italian news agency Nena-News.]

Spread the word