Author Thomas Frank Talks Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and His New Book, ‘Listen Liberal’

In his books What’s the Matter with Kansas? and The Wrecking Crew, writer Thomas Frank made a name for himself with his critiques of Republican politics. Now, he’s turning his eviscerating anthropological technique on the tribe of which he considers himself a member.

While the battle rages for the soul of the Republican Party, Frank sees Democrats in the throes of their own identity crisis. The one-time party of the working class has been co-opted by a hyper-educated elite, he argues in his just-published Listen Liberal. The book can be read as an argument that the anger propelling Donald Trump’s campaign is the product of short-sighted policy decisions made by Democratic technocrats.

By inveighing against the “professional class,” a meritocracy that, by his lights, is as rigidly status-driven and as averse to outsider voices as class based upon wealth, Frank is casting himself in the role of heretic. The author is from a family of Ph.Ds (his is from the University of Chicago in 20th century history and culture), and he’s a resident of Montgomery County, Maryland, a leafy Washington bedroom community where nearly 60 percent of residents hold a bachelor’s degree or higher — twice the national average.

On Sunday afternoon, just before leaving on a book tour that will cross the country (including a few stops in his native Kansas), Frank took a break from weekend housecleaning with his family to discuss his book, his favorite (and least favorite) politicians, the pluses and minuses of higher education and his vote in Maryland’s April 23 presidential primary. The conversation has been edited for length.

Kathy Kiely: Your last couple of books took aim at the Republicans. This one takes aim at folks more ideologically of your ilk.

Tom Frank: It’s the Democrats.

Why?

Oh I think it’s just as interesting a story with all the paradoxes and ironies. All the things that make for a compelling political story. And there’s also a great question, that we’re all wondering in year eight of, you know, the “hope presidency,” which is why has inequality gotten worse? Why has it gotten worse under a Democratic president whom everyone assures us is the most liberal of all possible presidents, if not a socialist or a Kenyan communist, you know?

It raises the obvious question with this wonderful liberal president in office, why has inequality continued to surge? Why have the gains of the recovery been monopolized by the top 10 percent or so of the income distribution?

Are you being facetious when you say Obama is such a liberal?

Oh I’m sort of joking. But I think he is a liberal. What I’m getting at is that liberalism itself has changed and that the Democrats aren’t who we think they are. That’s the answer to basically every question you want to raise about them for the last 30 or so years. They aren’t who you think they are. Their unofficial motto is that they’re the party of the people. That goes back to Jefferson and Jackson. And it’s just not so. This is a class party. I think the Republicans are as well. The Democrats are a class party; it’s just that the class in question is not the one we think it is. It’s not working people, you know, middle class. It’s the professional class. It’s people with advanced degrees. They use that phrase themselves, all the time: the professional class.

What is the professional class?

The advanced degrees is an important part of it. Having a college education is obviously essential to it. These are careers based on educational achievement. There’s the sort of core professions going back to the 19th century like doctors, lawyers, architects, engineers, but nowadays there’s many, many, many more and it’s a part of the population that’s expanded. It’s a much larger group of people now than it was 50 or 60 years ago thanks to the post-industrial economy. You know math Ph.Ds that would write calculations on Wall Street for derivative securities or like biochemists who work in pharmaceutical companies. There’s hundreds of these occupations now, thousands of them. It’s a much larger part of the population now than it used to be. But it still tends to be very prosperous people.

And how does that differ from who the Republicans are going after?

What I decided after researching this problem and reading a lot of the sociological literature on professionalism is that there’s basically two hierarchies in America. One is the hierarchy of money and big business and that’s really where the Republicans are at: the one percent, the Koch brothers, that sort of thing. The hierarchy of status is a different one. The professionals are the apex of that hierarchy. And these two hierarchies live side by side. They share a lot of the same assumptions about the world and a lot of the same attitudes, but they also differ in important ways. So I’m not one of these people who says the Democrats and the Republicans are the same. I don’t think they are. But there are sometimes similarities between these two groups.

Among other things, professionals tend to be very liberal on essentially any issue other than workplaces issues. So on every matter of cultural issues, culture war issues, all the things that have been so prominent in the past, they can be very liberal. On economic questions, however, they tend not to be. (dishes clattering) They tend to be much more conservative. And their attitudes towards working-class people in general and organized labor specifically is very contemptuous.

Where do you see evidence of that?

You mean politically? Well if you just look back at the history of Democratic governance — I look from the ’70s to the present. But if you look just back to the Bill Clinton administration: In policy after policy after policy, he was choosing between groups of Americans, and he was always choosing the interests of professionals over the interests of average people. You take something like NAFTA, which was a straight class issue, right down the middle, where working people are on one side of the divide and professionals are on another. And they’re not just on either side of the divide: Working people are saying, “This is a betrayal. You’re going to ruin us.” And professional people are saying, “What are you talking about? This is a no-brainer. This is what you learn on the first day of economics class.” And hilariously, the working people turned out to be right about that. The people flaunting their college degrees turned out to be wrong. I love that.

You go right down the line: Every policy decision he made was like this. The crime bill of 1994, which was this sort of extraordinary crackdown on all sorts of different kinds of people. And at the same time he’s deregulating Wall Street. So some people are getting crushed in the iron fist of the state, and other people are literally having the rules rolled back. No more rules for banking. We’re doing away with rules for interstate banking. We’re doing away with Glass Steagall. We’re ensuring that nobody can ever regulate derivative securities. These are all things they did when Bill Clinton was president. Or deregulating telecoms. Or capital gains tax cuts. It’s always choosing one group over another.

Obama, it’s slightly different, but it’s the same kind of story. By the way we should talk about them — Clinton and Obama — the similarities in their biographies. And not just them. If you go down the list of leading Democrats, leading Democratic politicians, what you find is that they’re all plucked from obscurity by fancy universities. This is their life story. Bill Clinton was from a town in Arkansas, goes to Georgetown, becomes a Rhodes Scholar, goes to Yale Law School — the doors of the world open up for him because of college.

But that’s sort of an old American truism, isn’t it?

Is it? Or is it that people would work their way up? People used to find opportunity in all sorts of places. But beginning in the 1960s, Americans decided that the right way to pursue opportunities was through the university. It’s more modern than you think. I was reading a book about social class from right after World War II. And the author was describing this transition, this divide between people who came up through their work, who learned on the job and were promoted, versus people who went to universities. And this was in the ’40s. But by the time Bill Clinton was coming up in the ’60s, university was essential. And you had that whole literature about the youth and the now generation and all that stuff in the ’60s — the counterculture. It was always taken for granted that you were talking about college kids, or kids that were going to college. And Bill Clinton really represents that. And you look at Barack Obama and it’s the same thing: plucked from obscurity by first Columbia and then Harvard Law and Harvard Law review. And he is famously a believer in the educational meritocracy. You just look at his cabinet choices, which are all from a very concentrated very narrow sector of the American elite. It’s always Ivy League institutions.

You had talked at one point in the book about two institutions that are slowly bankrupting America: Big Medicine and Big Learning. Talk to me about Big Learning and the role you see it playing.

Yeah this is something I’ve written a lot about, you know Big Learning and the annual tuition hike. Funny story, MIT, one of the crown jewels of American higher education. I forget what MIT costs — to go there for a year now, it’s something like 60 grand.

It looks like your kids are about college age.

My girl just started high school, so we’ve got some time yet. A friend of mine had gone to MIT back in the ’70s and I asked him how much it cost back then and it was like, oh a couple of thousand dollars a year. The tuition price spiral is one of the great landmark institutions of our country in the last couple of decades. I’ve written about it in great detail because I’m fascinated by it. I myself went through that and even got a Ph.D. I watched as my generation of Ph.Ds, who we all expected to become university professors, instead became adjuncts. It was one of the first places where we learned in a really first-hand way about flexible labor markets. And about the casualization of labor. When suddenly you’re not a tenured historian. You’re teaching a course that meets three times a week and you’re getting $1,500 for an entire semester. That was a shocking lesson but at the same time that was happening to us, the price of college was going up and up and up, because increasingly the world or increasingly the American public understands and believes that you have to have a college degree to get ahead in life. So they are charging what the markets can bear. Oh and by the way the other part of that coin — Big Pharma. You know, $1,000 a pill. And, basically when you are sick, you don’t have a choice, you have to take that pill.

Do you have a choice on Big Learning?

Not much of one. I mean, we have all accepted in this country that that’s the only way to get ahead. Every politician tells us that you have to have a college degree, and look, I’m in favor of education. I think people should be educated, should go to college. I think it’s insane that it costs as much as it does. And I think that the country is increasingly agreeing with me. The student debt crisis? This is unbearable. We have put an entire generation of young people — basically they come out of college with the equivalent of a mortgage and very little to show for it. It’s unbelievable that we’ve done this. My dad went to college basically for free. It wasn’t even that expensive when I went, in the early 1980s. This is unbelieveable what we’re doing to young people now and it can’t go on. No other country does this.

You seem to be suggesting, the way you talk about the Democrats, that somehow this is elitist and to pursue an education puts you out of touch with real people.

I don’t think so. Especially since we’re rapidly becoming a country where — what is the percentage of people who have a college degree now? It’s pretty high. It’s a lot higher than it was when I was young.

So what’s wrong with picking your cabinet from the top universities?

The problem is orthodoxy. One of the things we know about disciplines and especially academic disciplines is that they enforce a certain orthodoxy. And when you’re Barack Obama, choosing every single cabinet member from Harvard — you’re getting guys like Larry Summers, president of Harvard, to run your economic strategy, you are getting advice from a very limited slice of what’s available out there. But Obama always chooses orthodoxy. And so one of the points I make about the meritocracy — meritocracy being the ideology of the professional class — the idea that people who are on top are there because they deserve to be, because they’re the smartest, because they’re the best. One of the chronic failings of meritocracy is orthodoxy. You get people who don’t listen to voices outside their discipline. Economists are the most flagrant example of this. The economics profession, which treats other ways of understanding the world with utter contempt. And in fact they treat a lot of their fellow economists with utter contempt.

One of the things about a meritocracy, and this is a line I repeat many times in the book, there’s no solidarity in a meritocracy. The guys at the top of the profession have very little sympathy for the people at the bottom. When one of their colleagues gets fired, they don’t go out on strike. They don’t do that. This comes from personal experience. When academic labor force is becoming adjunctified, Uber-ized, whatever you want to call it, there’s no real protest from on high, from the leaders of academia. Here and there, yes people are very sympathetic and they feel bad about it but there’s no organized counter-effort. There’s no solidarity in this group, but there is this amazing deference between the people at the top. And that’s what you see with Obama. He’s choosing those guys.

I’m all in favor of government by expert. That’s very clear. You should have someone running something like the Department of Labor or the EPA or whatever, you should have someone who knows what they’re doing and knows what they’re talking about. There’s no doubt in my mind about that. But if you look at the Obama years at this meritocracy of failure — you know, with these guys at the Justice Department, they can’t figure out how to prosecute a Wall Street executive. They can’t figure out how to enforce antitrust. Or you look at the guys at the Treasury Department who are bailing out banks. This has been a disaster and it has been the best and the brightest who have done it. So you look at that and you start to wonder, maybe expertise is a problem.

But I don’t think so. I think it’s a number of things. The first is orthodoxy which I mentioned. The second is that a lot of the professions have been corrupted. This is a very interesting part of the book, which I don’t explore at length. I wish I had explored it more. The professions across the board have been corrupted — accounting, real estate appraisers, you just go down the list. But the third thing is this. You go back and look at when government by expert has worked, because it has worked. It worked in the Roosevelt administration, very famously. They called it the Brains Trust. These guys were excellent.

They gave us the best administration we’ve ever had, as far as I’m concerned. They were all highly educated, very intelligent people. They weren’t all from Harvard. Now Roosevelt himself went to Harvard and he had a number of advisers who did but his top advisers were drawn from all sorts of different places in American life. His attorney general, Robert Jackson, who he put on the Supreme Court — was a prosecutor at Nuremberg as a matter of fact — was a lawyer with no law degree. Harry Truman never went to college. Marriner Eccles ran the Federal Reserve — brilliant man, kind of a visionary; he was a small-town banker from Utah. Henry Wallace went to Iowa State, ran a magazine for farmers. Harry Hopkins, his right-hand man, was a social worker from Iowa. These were not the cream of the intellectual crop. Now he did have some Harvard- and Yale-certified brains but even these were guys who were sort of in protest. Galbraith: This is a man who spent his entire career at war with economic orthodoxy. I mean, I love that guy. You go right on down the list. Its amazing the people he chose. They weren’t all from this one part of American life.

Is there a hero in your book?

I don’t think there is.

Is there a villain?

I think Bill Clinton comes closest to that. But I wouldn’t call him a villain because it’s hard to hate Bill Clinton. I know the Republicans do. But even those guys when they meet him in person — he’s such a charming man, by all accounts. I’ve never met him. I’ll tell you a story about him. It’s not about him; it’s about me. I went to his presidential library — I’m a Clinton skeptic, and have always been since he was elected. So I went to his presidential library and I was prepared to heap scorn on everything. I was writing about it for Salon. And I took that tour where you listen to his voice explaining all the exhibits to you. I loved the man, by the time I was done. I was like, wow, this guy was great. Why can’t he be president again, you know? He’s such a raconteur. And he’s so smart. Brilliant anecdotes and very touching stories about things. And he has that wonderful voice. And like I say, I’m a big Clinton skeptic and by the end of the tour, it was like what a great man!

It’s weird because Obama doesn’t have that. Obama’s kind of cold. But Obama inspired such passion in 2008. And I was one of those people who thought Obama was exactly the right person for the job.

And now? Now what do you think?

Well you look back over his record and he’s done a better job than most people have done. He’s no George W. Bush. He hasn’t screwed up like that guy did. There have been no major scandals. He got us out of the Iraq war. He got us some form of national health insurance. Those are pretty positive things. But you have to put them in the context of the times, weigh them against what was possible at the time. And compared to what was possible, I think, no. It’s a disappointment.

So what should he have done?

I think he should have been a lot more aggressive, first of all with the Wall Street banks. But take a step back. The overarching question of our time is inequality, as he himself has said. And it was in Bill Clinton’s time too. Although the issue receded a little bit in the late ’90s. But when Clinton ran in ’92, they were arguing about inequality then as well. And it’s definitely the question of our time. The way that issue manifested was Wall Street in ’08 and ’09. He could have taken much more drastic steps. He could have unwound bailouts, broken up the banks, fired some of those guys. They bailed out banks in the Roosevelt years too and they broke up banks all the time. They put banks out of business. They fired executives, all that sort of thing. It is all possible, there is precedent and he did none of it.

What else? You know a better solution for health care. Instead he has this deal where insurance companies are basically bullet-proof forever. Big Pharma. Same thing: When they write these trade deals, Big Pharma is always protected in them. They talk about free trade. Protectionism is supposed to be a bad word. Big Pharma is always protected when they write these trade deals.

You talk about “a way of life from which politicians have withdrawn their blessing.” What is that way of life?

You mean manufacturing?

You tell me.

A sort of blue-collar way of life. It’s the America that I remember from 20, 30, 40 years ago. An America where ordinary people without college degrees were able to have a middle class standard of living. Which was — this is hard for people to believe today — that was common when I was young. It makes me feel like an old person to say that. It makes me feel like my dad. But that was common when I was a child. Today that’s disappeared. It’s disappearing or it has disappeared. And we’ve managed to convince ourselves that the reason it’s disappeared is because — on strictly meritocratic grounds, using the logic of professionalism — that people who didn’t go to college don’t have any right to a middle-class standard of living. They aren’t educated enough. You have to be educated if you want a middle-class standard of living.

What do you think caused that disappearance of that way of life you talked about and is it possible to get it back in your view?

When I look at the problem of inequality, I see a number of causes but one of them is that workers don’t have as much power over conditions of employment as they used to. And there have been so many different mechanisms brought into play in order to take their power away. One is the decline of organized labor. It’s very hard to form a union in America. If you try to form a union in the workplace, you’ll just get fired. This is well known. Another, NAFTA. All the free trade treaties we’ve entered upon have been designed to give management the upper hand over their workers. They can threaten to move the plant. That used to happen of course before NAFTA but now it happens more often.

Basically everything we’ve done has been designed to increase the power of management over labor in a broad sociological sense. And then you think about our solutions for these things. Our solutions for these things always have something to do with education. Democrats look at the problems I am describing and for every economic problem, they see an educational solution. That’s always their answer. More student loans. More job training. Get more kids into colleges. Give everyone a chance to go to Harvard. That’s always their answer. That’s misdiagnosing the problem, in my view. The problem is not that we aren’t smart enough; the problem is that we don’t have any power.

Why do you think that is?

I go back to the same explanation which is that Obama and company, like Clinton and company, are in thrall to a world view that privileges the interest of this one class over everybody else. And Silicon Valley is today when you talk about the creative class or whatever label you want to apply to this favored group, Silicon Valley is the arch-representative. And one of the funny things, as I was writing this book, you know who Eric Schmidt is? The CEO of Google. He keeps reappearing in my narrative. He just keeps popping up. So there’s a, they give a prize to Deval Patrick, the governor of Massachusetts, at one point and, whoa!, here’s Eric Schmidt giving a speech. Hillary Clinton, secretary of state, and she’s in the Netherlands and she’s giving a speech and she gives a shoutout to Eric Schmidt, who’s right there in the audience. And then there’s another: Oh yeah, Obama, right after he’s been elected, has this economic advisory group and it includes — hey! There’s Eric Schmidt. He just keeps popping up. It’s like the where’s Waldo of modern liberalism. So you start to understand, this is a clue. This is the kind of guy that they really admire, that they look up to. His views are gold.

So do you think it’s just a matter of being enthralled or is it a matter of money? Jobs?

Oh the revolving door! Yes. The revolving door, I mean these things are all mixed together. When you talk about social class, yes, you are talking about money. You are talking about the jobs that these people do and the jobs that they get after they’re done working for government. Or before they begin working for government. So the revolving door — many people have remarked upon the revolving door between the Obama administration and Wall Street. And by that I mean both coming and going: Rahm, Larry Summers, Bill Daley. You go down the list. All these guys have worked briefly for investment banks, private equity or something like that. And then the guys leaving the administration to go do those jobs, it’s really quite incredible. It includes people like Tim Geithner. The treasury secretary for God’s sakes.

Now it’s between the administration and Silicon Valley. There’s people coming in from Google. People going out to work at Uber. You know.

You’re very suspicious of the digital economy.

Well in some ways it’s very convenient. I mean it accomplished miracles. Like I can turn in my book without putting a manuscript in the mail. And I don’t have to retype it. You know, the productivity advances that it has made possible are extraordinary. What I’m skeptical of is when we say, oh, there’s a classic example when Jeff Bezos says, ‘Amazon is not happening to book-selling. The future is happening to book-selling.’ You know when people cast innovation — the interests of my company — as, that’s the future. That’s just God. The invisible hand is doing that. It just is not so. Every economic arrangement is a political decision. It’s not done by God. It’s not done by the invisible hand — I mean sometimes it is, but it’s not the future doing it. It’s in the power of our elected leaders to set up the economic arrangements that we live in. And to just cast it off and say, oh that’s just technology or the future is to just blow off the entire question of how we should arrange this economy that we’re stumbling into.

Who are you going to vote for in the Maryland primary?

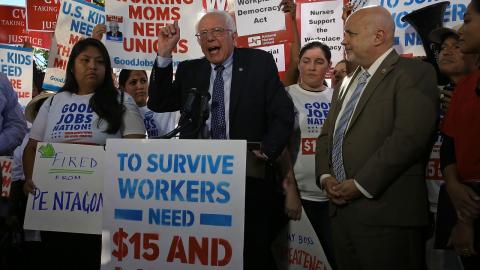

Oh. I am looking forward to casting my ballot for Bernie Sanders.

Tell me why. Because you say in your book you may end up voting for Hillary.

I may end up voting for Hillary this fall. If she’s the candidate and Trump is the Republican. You bet I’m voting for her. There’s no doubt in my mind. Unless something were to change really really really dramatically.

But yes, Bernie Sanders because he has raised the issues that I think are really critical. He’s a voice of discontent which we really need in the Democratic party. I’m so tired of this smug professional class satisfaction. I’ve just had enough of it. He’s talking about what happens to the millennials. That’s really important. He’s talking about the out-of-control price of college. He’s even talking about monopoly and anti-trust. He’s talking about health care. As far as I’m concerned, he’s hitting all the right notes. Now, Hillary, she’s not so bad, right? I mean she’s saying the same things. Usually after a short delay. But he’s also talking about trade. That’s critical. He’s really raising all of the issues, or most of the issues that I think really need to be raised.

Because your book is so tough on Bill Clinton—you yourself said he’s the closest thing to a villain in the book—does Hillary deserve the same degree of suspicion?

No, she’s her own person. But she should be held responsible for things when she says she supports them. I actually tried to avoid taking Hillary to task for things that happened during the Clinton years because I don’t think that’s fair to do that. However, take something like welfare reform, which was regarded at the time as one of Bill Clinton’s great achievements. Today, not so much. But she was very proud of her role in this and encouraging him to sign it and get it through. She’s written about this in one of her memoirs. When she does that and says, I lobbied for it, then she should be held responsible.

But that’s not my main critique of her. My main critique is that she, like other professional class liberals who are so enthralled with meritocracy, that she can’t see this broader critique of all our economic arrangements that I’ve been describing to you. For her, every problem is a problem of the meritocracy: It’s how do we get talented people into the top ranking positions where they deserve to be. And this is always especially with reference to her own problems with becoming president, with becoming the first woman president. Remember the glass ceiling, putting cracks in the glass ceiling? She talks about this all the time. For good reason. And that’s a good issue. And there shouldn’t be glass ceilings. People who are talented should be able to rise to the top. I agree on all that stuff. However that’s not the problem right now. The problems are much more systemic, much deeper, much bigger. The whole thing needs to be called into question. So I think sometimes watching Hillary’s speeches that she just doesn’t get that. She just automatically gravitates back to this meritocracy thing. You know about the talented rising to the top and the barriers that keep the talented from rising to the top. That’s not the problem.

That sort of gets to one of the questions I was going to ask you: You take some tough shots at her, you take some really tough shots at Obama, Deval Patrick — all of them are trailblazers.

Yeah

And somebody could say, you’re just nostalgic for the white-guy ascendency.

I dunno. I like Jesse Jackson. I like him a lot. I thought he kind of rocked. Look, my own opinion about this is that this is Elizabeth Warren’s year. She’s the one who should be up there running. If she had run, she would be, I think, crushing it in the polls. And I’m really sorry that she didn’t run. As far as I’m concerned, she’s the one who has best articulated all of the things that I’m describing. Bernie Sanders, yeah, he’s great. But she’s a better candidate in my view. And it’s a real shame she didn’t run. But I would also point out to you that these people are not friends of — well, how to put this: You look at Bill Clinton and things like welfare reform and the crime bill of ’94, these were not nice things to do to black voters who had supported him. This is betrayal in a kind of awful way. As was NAFTA, which did terrible harm to the working-class people that had voted for him. So I have trouble with the idea that these guys are automatically — that that’s who they represent.

Deval Patrick, by the way, is another really interesting story. Again a person of humble circumstances who was plucked from obscurity by a fancy educational institution. A very talented guy. And again, a guy that it’s hard to dislike. So I watched a whole bunch of his speeches and he’s a real charming guy. I would love to be his friend. It’s the same with Obama. I have this weird thing with Obama. I disagree with Obama about lots of things but I like the guy as a person. I really like him. I’m disappointed with him but, great guy. And I voted for him twice.

Would you vote for him again?

Depends on who he’s running against of course. If he’s running against Trump, yeah, of course I would.

Spread the word