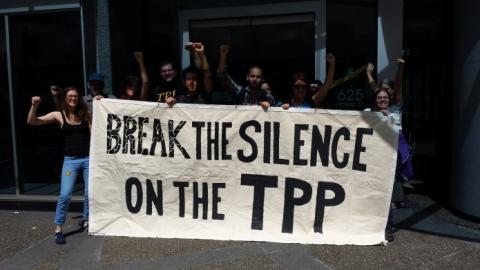

After the November election, all eyes will be on President Obama to see if he will follow through on his vow to push for a vote during a lame-duck session of Congress on the wildly unpopular Trans-Pacific Partnership.

In a previous interview with Inequality.org, AFL-CIO deputy chief of staff, Thea Lee, explained why the U.S. labor movement strongly opposes the trade pact. She described the TPP as yet one more deal that would put downward pressure on U.S. labor conditions by further opening up the U.S. market and giving additional protections for U.S. corporations looking to move jobs offshore. Lee has been a leader in building international solidarity against such corporate-driven trade agreements.

To bring a developing world perspective to this issue, we turned to Institute for Policy Studies associate fellow Manuel Pérez-Rocha, who has spent more than two decades working with social movements for an alternative approach to trade that would put the interests of people and the environment first. His home country of Mexico is one of the 12 nations negotiating the Trans-Pacific deal, despite more than 20 years of experience with the failed blueprint for the TPP — the North American Free Trade Agreement.

NAFTA promoters claimed it would make life much better in Mexico and would reduce the pressure to immigrate to the United States. What has happened since the agreement went into effect in 1994?

Pérez-Rocha: Mexico’s poverty has increased, wages have been slashed, and the country now has to import 45 percent of its food (Back in 1994, it imported only 15 percent). By lowering trade barriers and cutting subsidies for small producers, the Mexican government abandoned national food production to favor imports. This has meant declining production, employment, and income, and increasing inequality, poverty, and migration pressures.

The vacuum left behind has been occupied by organized crime. The increase in violence and public insecurity in the countryside, and really in all of Mexico, has a clear link to NAFTA. Mexico has lost more than 100,000 lives, and tens of thousands of people have “disappeared” under the so-called war on drugs.

Some claim NAFTA created jobs in the border factories. Is that not true?

Pérez-Rocha: The jobs that were created were low-road jobs, without basic labor protections and with low wages and often dangerous working conditions. And because NAFTA prohibited governments from requiring that foreign investors use domestic suppliers, the ripple effects of this investment plummeted. When unions and other groups turned to the NAFTA labor side agreement to try to get some recourse for rights violations, it was a huge waste of time. Compared to NAFTA’s investment agreement rules, under which U.S. and Canadian corporations have successfully sued Mexico for hundreds of millions of dollars, the labor side agreement has no teeth. And when workers struggled to push up wages, many of the companies simply moved to China or other lower-wage areas.

Who has profited from NAFTA?

Pérez-Rocha: Mexico now has 12 billionaires. We didn’t have a single one in 1987, before our government started selling off public enterprises at a discount to cronies and introducing other free market reforms to lay the groundwork for NAFTA. Carlos Slim, with $50 billion, is the 4th wealthiest person in the world. Slim made his fortune from the privatization of the formerly state-owned Telefonos de Mexico company. Ricardo Salinas Pliego made his billions through the privatization of a national TV company (now Televisión Azteca). Others, like German Larrea and Alberto Bailleres, became extremely wealthy off industries that benefited from lower trade barriers, like mining, while causing terrible environmental impacts.

What other new privileges have gone to the top 1% under NAFTA?

Wealthy foreign investors got the completely unprecedented power to sue governments in obscure, unaccountable, and private tribunals, like the World Bank’s International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes. Under the investor-state dispute settlement system, they can sue in international tribunals for millions and even billions of dollars over government actions that might reduce their profits. Canada and Mexico have lost many cases under NAFTA’s investment rules.

I’ve spent much of my time in recent years working in solidarity with people who are trying to fight these cases. In El Salvador, for example, we’ve been supporting activists who’ve been working for six years against a case brought by the Canadian Pacific Rim company (owned by the Australian Oceana Gold). The company is demanding $250 million, simply because the government is acting to protect the country’s primary watershed from poisonous gold mining.

A ruling in this case is expected soon and if it goes against El Salvador, it should be a huge wake-up call about the TPP. Even if the tribunal “favors” El Salvador, this small country should not have had to go through all of the emotional pain and financial suffering related to this case, including having to pay millions for its legal defense. The TPP would allow corporations to file the same kinds of investor-state lawsuits.

After working on these bad trade deals for so long, what gives you hope?

Social movements have defeated corporate schemes like the TPP several times in the past. For example, in 1998 the proposed Multilateral Agreement on Investment failed after France and other countries withdrew from the negotiations in response to civil society demands. In 2005, negotiators gave up on the U.S.-led Free Trade Area of the Americas, a trade pact that was to include 32 countries in the Western Hemisphere.

Today, the TPP and the proposed U.S.-European Union trade deal (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) are at an impasse and in deep peril because of the power of social movements. In the United States it becomes clear before every election that so called “free trade” is very unpopular. Obama said during his presidential campaign that he would renegotiate flawed deals like NAFTA. Today both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump claim to be against the TPP. This demonstrates that free trade agreements can be obtained only through anti-democratic means.

What gives me hope is that citizens around the world know very well how damaging the free trade agenda is for people and the planet and that we are as ready as ever to take action.

Manuel Pérez-Rocha is an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies and is an associate at the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam. Previously he worked with the Mexican Action Network on Free Trade.

Spread the word