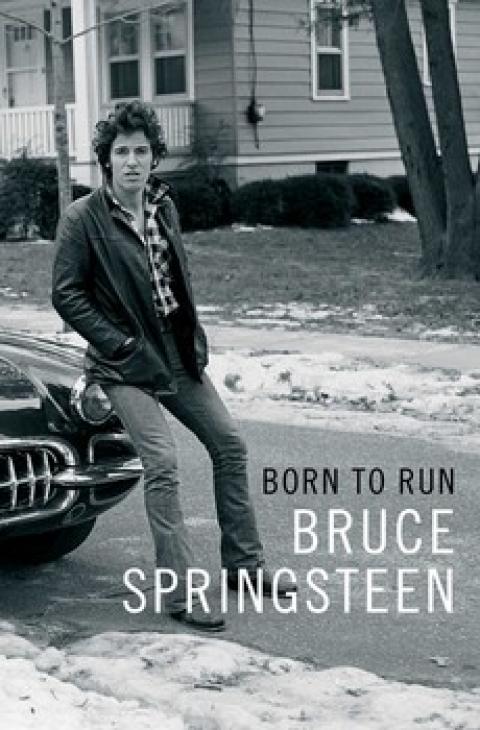

Born to Run

Bruce Springsteen

Simon & Schuster

ISBN 9781501141515

So what else was he going to call it, asked one reviewer of the big new Bruce Springsteen autobiography, Born to Run. “Born to Run,” as you may know, was the title song of the 1975 album that put Springsteen on the-covers of Time and Newsweek, whence he became the free-wheeling, hard-touring American hero we know today. But as often happens with this man of the people, the song is trickier than it appears — the lyric more about feeling trapped than breaking free, the music an exhilarating up that’s all about escape. You could say it’s too grand — Springsteen cites rebel-rousing guitar twanger Duane Eddy, operatic rockabilly Roy Orbison, and convicted megalomaniac Phil Spector as inspirations. But its grandeur is subsumed by the layered momentum of 85mph drums, blood-rousing piano, and tinkling glockenspiel. Is it true, as Springsteen feverishly declares, that he and Wendy plan to die together in their “suicide machines”? Only metaphorically, the music insists. They were born to run again — and then again.

Of course, Springsteen could have chosen a parallel title more in keeping with his grandiose side: Born in the U.S.A., after the title song of the 1984 album he went deca-platinum on, which framed a dark antiwar lyric inside a solemn, deceptively martial groove. Although soon misprised by Ronald Reagan and lesser liars, it became the Ur-source all the Springsteen books whose titles sport phrases like “American poet,” “American song,” “American soul,” and the inevitable “American dream.” Yet Springsteen still called his autobio Born to Run, and properly so — he’s not really a pretentious guy, and anyway, the title serves to emphasize a running metaphor. More times than I had the wit to count, he feels compelled to get on his motorcycle or in his car and race around this U.S.A. he was born in, often for days or even weeks at a time. Then he comes home, generally in a better mood. After 30-plus years of psychotherapy, he’s still running.

That’s right, psychotherapy. By now even his most ardent fans have figured out that their hero isn’t just a fun-loving bundle of energy fronting three-hour concerts that exhilarate you for your money, and in 2012, David Remnick honored his complexity with a massive New Yorker profile in which therapy played a crucial role. But Born to Run doubles down on the gambit. It reads like it was written by an analysand — he thanks his shrink by name, in the text rather than the acknowledgments — and that’s good. This is someone who’s thought a lot about his upbringing, and not just the brooding father sitting in the dark kitchen with his six-pack and smokes who was a fixture of his stage patter from the beginning.

Far more incisive than any biographer’s version, Springsteen’s account of his early years — say pre-Beatlemania, which hit when he was 14 — lasts over 50 pages. Although his parents both worked, his mother steadily as a legal secretary and his father usually as whatever he could get, to call the Springsteens lower-middle-class would be pushing it: when he was young, a single kerosene stove provided all the heat in the house. Yet his mother came from money even if it was damaged money — her thrice-married father was a lawyer who did three years in Sing Sing for embezzlement and held court thereafter in a proverbial house on the hill. But it’s even more striking that his paternal grandmother was young Bruce’s primary caregiver, indulging him so unstintingly that he refused to live with his parents even when he reached school age, sleeping down the block in his grandmother’s bed with his grandfather exiled to a cot across the room. “It was a place where I felt an ultimate security, full license and a horrible unforgettable boundary-less love. It ruined me and it made me.”

There are no typical childhoods anyway, but this part of the book, which I wish was even longer, cracks through the working-class/South Jersey typology that has long encrusted Springsteen’s myth. It’s weird. And it’s written. Put aside your literary preconceptions and taste the two sentences I just quoted. They’re a mite awkward, the three commaless adjectives barely in control. But they make a big point loud and clear. Autobiographer Springsteen doesn’t command the brash fuck-you eloquence of rock memoirists Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, and Richard Hell, each quite distinct yet all of a piece in their aesthetic verve and acuity. He’s cornier. But there’s a life to his prose that such high-IQ rock autobiographers as Pete Townshend and Bob Mould don’t come near, a life redolent of the colloquial concentration and thematic sweep of his songwriting. Sure he bloviates sometimes. But the book moves and carries you along.

In Remnick’s profile, Springsteen’s manager-for-life, intellectual mentor, and dear friend Jon Landau (who as the world’s wealthiest former rock critic could have supported more pages, though he gets his share) calls Springsteen “the smartest person I’ve ever known.” Intimates could probably say the same of Dylan, Smith, Hell, for that matter Townshend and Mould. But never think Springsteen has less brain power than these art heroes. Insofar as his book is corny, that’s a conscious aesthetic choice he’s made for the entirety of his career. It’s just that as he’s matured he’s gotten more conscious about it — and even smarter. Sure he’s all about Jersey, as he should be. But his first Jersey was the late-’60s one, where a hospital in Neptune refused to treat the head injury of a long-haired teen named Bruce who came in after a serious motorcycle accident — there are outsiders everywhere, and the longhair gravitated to them and knows he owes them. Moreover, he tenders many thanks to Greenwich Village — as a human being, because it bristled with life-changing alternatives to Jersey’s manifold limitations, and as an artist, because its poesy-spouting singer-songwriters and bohemian esprit lured him far enough away from his home turf to reflect on it with perspective.

Born to Run is a true autobiography, a thorough factual account of the author’s life until now. But since it’s an artist’s autobiography, it can’t do that job of work without telling us stuff about his art. For some this might mean the 12 out of 79 chapters whose italicized titles match those of albums he deems worthy of individual attention, which I found merely useful except as regards his overrated post-9/11 The Rising, which indicates that much of it was written pre-attack and then retrofitted to the catastrophe New Jersey’s poet laureate felt compelled to address, where the much sharper 2012 Wrecking Ball was protest music from its conception. Others will savor the celebrity gossip that’s always a selling point of these books — Sinatra knowing a paisan when he sees one, or “the GREATEST GARAGE BAND IN THE WORLD” prepping his “Tumbling Dice” cameo at their 2012 Newark show with a single five-minute rehearsal space run-through that blows his fanboy mind. But for me both were dwarfed by his reflections on persona and performance.

Never in Born to Run does Springsteen claim the mantle of “authenticity” he’s forever saddled with. “In the second half of the twentieth century, `authenticity’ would be what you made of it, a hall of mirrors,” he says, but also, mirror fans: “Of course I thought I was a phony — that is the way of the artist — but I also thought I was the realest thing you’d ever seen.” And if you’d prefer your analysis straighter, there’s: “I, who’d never done a week’s worth of manual labor in my life (hail, hail rock ‘n’ roll!), put on a factory worker’s clothes, my father’s clothes, and went to work.” No matter how you slice it, it’s an act, or to use a word he loves, a show: “You don’t TELL people anything, you SHOW them, and let them decide.” To convince them, he works hard, Jack, exerting himself as unrelentingly as any manual laborer, because only the audience’s boundary-less love can satisfy that deep, ruinous emotional hunger. Yet what you think you see is not necessarily what you’re getting. The book’s most dazzling single passage is a phantasmagoric two-page recollection of the frighteningly self-conscious “multiple personalities” who battled within him during his very first European performance, at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in 1975. Ordeal over, he returns to his hotel room “underneath a cloud of black crows” and feeling like a failure. Only he was wrong — the performance became legendary, and when he worked up the guts to watch film of it 30 years later all he saw was “a tough but excellent set.”

Impinging even on these aesthetic reflections, however, you’ll notice the familial history that provides not only this full autobiography’s substratum but its true subject. You may want more about, say, Pete Townshend, who is quoted fruitfully on how the rock band makes de facto family members out of people you happen to meet as a kid, and his old pal Steve Van Zandt gets plenty of ink, as do departed saxophone colossus Clarence Clemons and departed organ grinder Danny Federici. But Springsteen leaves no doubt that although the show is his lifeline and he may die running, his love life in the broadest sense is what got 509 pages out of him. Offstage he’s been loved and loving from an early age, but between his unconditional grandmother and his silent father, learning to stick at it has been quite the sentimental education. Clearly Dr. Myers was his best teacher until he finally settled on homegirl turned backup singer Patti Scialfa in 1988 and married her in 1991. But although he’s not bragging, much of the credit redounds to him.

Full autobiographies generally portray elders more acutely than youngers for the obvious reason that the elders are dead — they can’t stop you and their feelings won’t get hurt. But in Born to Run, Bruce’s father Doug ends up packing more mojo than Van Zandt or Landau or Clemons or even Scialfa, and that’s unusual. The story returns to Doug when it doesn’t have to — no one would have missed that fishing trip. The account of his senescence, when he was finally diagnosed with not one but two major psychological disorders, is topped off with a bravura description of his body — “elephant stumps for calves and clubs for feet” — in the final hours of his life. Which in turn is topped by a briefer tribute to Bruce’s miraculous mother, still radiating “a warmth and exuberance the world as it is may not merit” as she navigates Alzheimer’s at 91.

Scialfa doesn’t resonate as vividly as his parents — discretion no doubt intervened, and is presumably why the redolently homely divorce case naming Bruce as a respondent goes unmentioned. Nonetheless, she’s the silent hero of this book. Springsteen was never a dog, but from his teens he was a serial monogamist with lapses who acknowledges with less vanity than chagrin that he went through a lot of women, including his first wife, the model Julianne Phillips. Scialfa benefited from Dr. Myers’s spadework as well as the failed Phillips experiment. She’s no beacon of calm because that wouldn’t work at all — she’d better the hell stand up to him. But she gives her husband the superstar version of a normal life he’s clearly craved since a childhood that taught him he couldn’t have one — a life both his maturing art and his everyman politics impelled him toward. Even the three kids are richly described, with discretion deftly served by focusing on their very different early years — in a passage few autobiographers would adjudge worth their literary while, Scialfa jawbones him first into getting up with the kids and learning to make pancakes and then into giving young Sam his late-night bottle-and-story. As he puts it: “She inspired me to be a better man, turning the dial way down on my running while still leaving me room to move.”

Born to run, yet happy with room to move. The artist’s story is worth telling. But so is the man’s.

Robert Christgau's writing on music and books, including his long-running music Consumer Guide, can be found at robertchristgau.com. His most recent book is the memoir Going into the City.

Spread the word