Trump Does Have an Obamacare Replacement Plan -- and it Would Cause 21 Million to Lose Coverage

Donald Trump does have a plan to replace Obamacare — and as a president with a Republican Congress, a clear path to passing it.

In broad terms, Trump's plan looks a lot like the dozen or so other Republican Obamacare repeal plans that have come out over the past few years. Trumpcare allows insurance companies to go back to refusing coverage for preexisting conditions, a key barrier to coverage before Obamacare's coverage expansion.

The plan would, according to outside analysts, increase the number of uninsured Americans by 21 million people.

Trump says in his plan that America "must also make sure that no one slips through the cracks simply because they cannot afford insurance." In a recent Republican debate, Trump promised that, if elected, he would "not allow people to die on the sidewalks and the streets of our country" for lack of access to health insurance.

Trumpcare, explained

Trumpcare has seven main policy points. Many of them are Republican orthodoxy, like allowing insurance sales across state lines (part of the Republicans' 2010 Pledge to America) and fostering a greater reliance on health savings accounts (a favorite policy proposal of Mitt Romney during the last campaign cycle). And, of course, Trump repeals Obamacare.

The key insurance reform that Trumpcare settles on is allowing individuals to deduct their premiums from their tax returns. This would give preferential tax treatment to the policies that individuals purchase, much like employer-sponsored plans (which the government does not tax). And it might help lower the premiums of people who buy health insurance coverage.

This part strays in a nuanced but important way from recent Obamacare repeal plans — and makes Trump's proposal much less favorable to low-income people than other Republican alternatives to the Affordable Care Act.

Harvard's John McDonough's analysis of eight recent replacement proposals shows that most follow Obamacare in relying on tax credits rather than deductions. Credits deliver an equal dollar value to all households, whether rich or poor. Deductions are much more valuable to high-income families who pay in high tax brackets, and often do nothing to help low-income families who likely don't itemize their deductions at all.

Putting all that aside, Trumpcare erects a massive barrier to coverage: It allows insurers to deny coverage to sick people. This is pretty typical of Republican Obamacare replacement plans; only one of eight plans that McDonough analyzed required insurers to offer coverage to all individuals, even if they were especially sick.

Trumpcare would also allow the return of underwriting, where insurers can charge some subscribers more because they're especially sick. Under Trumpcare, a cancer patient could, theoretically, deduct his or her premium, which could make coverage more affordable — but that cancer patient might not be able to get coverage or have the cash to pay for it in the first place.

There are at least 60 million Americans with preexisting conditions. Some of them have coverage under Obamacare. If Trumpcare became law, there's no guarantee they'd get to keep it. It's a pretty big crack to slip through.

Trumpcare would cost more than Obamacare — and cover fewer people

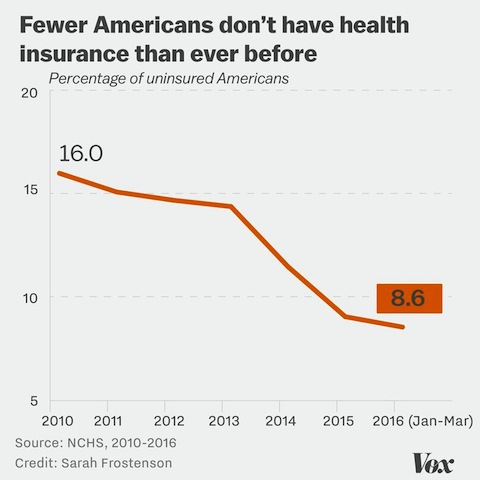

The uninsured rate has fallen to an all-time low under President Obama — but Trumpcare would change all that.

Repealing Obamacare would leave an additional 22 million people uninsured, according to CRFB estimates using Congressional Budget Office projections. These people would mostly be losing coverage they get through the health law's marketplaces and its Medicaid expansion. Obamacare doesn't offer universal coverage; CBO estimates that in 2018, it will still leave 27 million people uncovered. Still, it outperforms Trumpcare by a lot, because Trumpcare would add 21 million to that group, for a grand total of 48 million uninsured Americans.

About a million of those who lost Obamacare would gain insurance through Trump's proposal to allow insurance plans to sell across state lines. That would, theoretically, allow shoppers in highly regulated markets to gain access to less expensive coverage. (The Upshot's Margot Sanger-Katz has a good summary of this part of the Trump plan here.)

But even with the sale of insurance across state lines, Trump's plan would leave 21 million Americans without coverage.

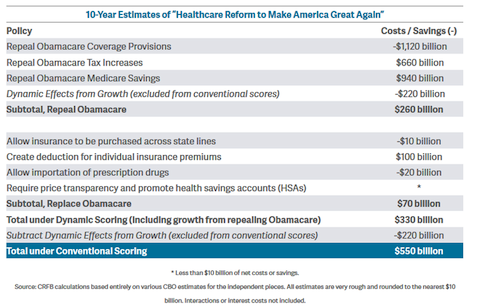

Then there is the cost side of Obamacare. The health law does spend $1.1 trillion extending coverage to millions of Americans over the next decade. It more than offsets that spending, however, with $660 billion in new taxes and $940 billion in Medicare spending cuts.

This ends up making Trumpcare hundreds of billions of dollars more expensive than Obamacare. Trumpcare raises federal spending $330 billion under dynamic scoring (a model that estimates faster economic growth due to Obamacare repeal). If you use conventional scoring, which does not assume faster economic growth, the cost is $550 billion.

Trumpcare does have a few money-saving provisions, like allowing Americans to import prescription drugs from across the border. But that saves only about $20 billion — a far cry from the taxes and Medicare cuts it repeals.

Trumpcare is still a broad outline — and it will fall largely to Congress to decide what happens next

Trump will be working with a Republican majority in both the Senate and the House, who would shape whatever an attempt at Obamacare repeal would look like. Given that Trumpcare is still very much a broad outline, some experts expect that Congress would do much of the work figuring out what happens next.

“I would envision Trump looking to Congress to drive the replace process, just as the Obama administration did with the Affordable Care Act,” says Chris Condeluci, who worked as tax and benefits counsel for the Senate Finance Committee's Republicans during the Affordable Care Act debate.

Republicans have done a good deal to flesh out how they would repeal Obamacare, skirting the need for a filibuster-proof, 60-vote majority by using the reconciliation process. But they still haven’t written out legislative language for what their replacement plan might look like.

“I don’t think the two [repeal and replace] would come in tandem,” Condeluci says. “Replace needs to be litigated to a greater degree than it has before.”

House Republicans did publish a document outlining their Obamacare replacement plan this summer, called “A Better Way.” It envisions many health policy proposals that have become common in conservative plans, like block-granting Medicaid and allowing insurance sales across state lines.

But as Condeluci points out, that paper “isn’t in legislative form, and the Senate hasn’t weighed in.”

Spread the word