At age 13, Marco traveled with his grandmother, sister and uncle to Miami. Fleeing persecution in Guatemala, he traveled via Mexico to the US for a better life. Even without legal status, he prefers living here.

Marco is now one of thousands of undocumented students attending college in the United States. Born in Mixco, a province outside of Guatemala City, Marco began his journey from Guatemala to the United States in January 2010. During childhood, he was pushed around and bullied at school and in his neighborhood. He was being raised by his extended family because his father left to work in the US in 2002 and his mother followed shortly after in 2004. By the time Marco would arrive in Florida, he had spent half his life living apart from his parents.

Upon arrival in Sonora, Mexico, Marco and his family had to wait several weeks for their coyote to make proper travel arrangements, which involved arranging for two children with mobility disabilities (13-year-old Marco and his 8-year-old sister) to be transported over the wall that separates Mexico from the US. In order to get Marco over the wall, the coyote and Marco's uncle wrapped a blanket around him and lifted him up and over. A car was supposed to meet them in Nogales, Arizona, but it never showed up. Instead, Marco and his family were apprehended and taken to the local Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) station. He described the cell that his family was put in that first night as being large, packed and cold. Like thousands of other immigrant detainees, they were forced to stay in a hielera, or icebox, cells that are kept at freezing cold temperatures in ICE detention facilities.

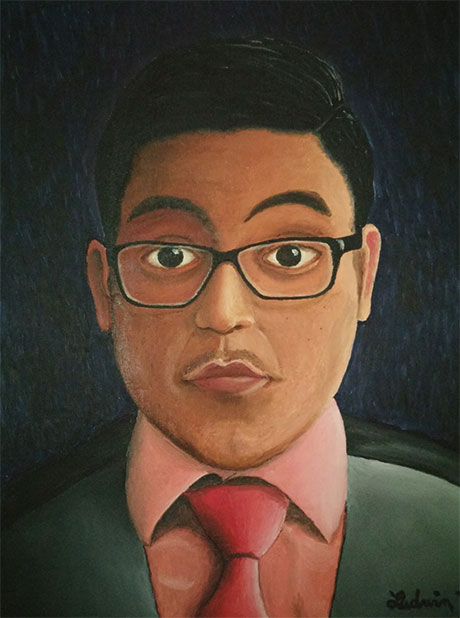

Self-portrait of Marco. (Photo: Marco)Self-portrait of Marco. (Photo: Marco)Within a week, Marco and his sister were placed with a Mexican-American foster family in Texas. His uncle and grandmother were both deported back to Guatemala. The Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service helped arrange the temporary foster placement, schooling and a plane ticket to Miami where they would be reconnected with their parents after nearly a decade of separation.

Marco spoke no English when he entered 6th grade at a local middle school. He was in ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) classes for the next two and a half years. By 9th grade he was able to enroll in regular classes, by 10th grade he enrolled in honors classes and as a junior he took an AP class.

Self-portrait of Marco. (Photo: Marco)

When Marco began to think about college, his primary concern was how he was going to pay for it. As an undocumented student, he didn't qualify for any federal financial assistance or student loans. Deep into his last semester of high school, he met Julio Calderon, an organizer at the Florida Immigration Coalition who works on access to higher education for immigrant youth. Julio assured him that there was a bright spot in the application process: House Bill 851, which allows high school graduates who've completed three consecutive years of high school to be eligible for in-state tuition at public colleges and universities -- regardless of their immigration status -- had recently passed.

Calderon travels to high schools and colleges across South Florida working to inform school personnel and immigrant students with temporary status or no status at all about their options for higher education. He explains that with the introduction of DACA, students were "more likely to believe that they can go to college simply because they have a Social Security Number."

In 2012, President Obama passed DACA, a legislative policy to ensure that certain undocumented immigrants to the United States who entered the country before their 16th birthday and before June 2007 receive a renewable two-year work permit, a Social Security Number and exemption from deportation.

President-Elect Donald Trump, however, has vowed to end DACA once he enters office in January, making hundreds of thousands of young people fearful of deportation and feeling like their education could be in jeopardy. For students who are undocumented, the fear is even greater.

Nevertheless, until Trump's administration carries out its promised attack on DACA, the program will continue to offer what Andres Ramirez, a professor at Florida Atlantic University, calls an "extra protection from the government." He argues that many undocumented families feel alienated from college culture. Parents who are monolingual and may not have gone to college themselves are prevented from supporting their children in a meaningful way -- filling out proper financial paperwork, applying to scholarships, choosing the right school. In addition, Ramirez says the college application process requires "disclosure of a secret that families have safeguarded for years." The fear of being exposed to a state institution introduces a host of fears and sometimes prevents kids from going to college.

Because Marco arrived in 2010, he does not qualify for DACA. And even with HB 851, he still couldn't afford his preferred university, where he was hoping to study architecture. The only option was a community college, where he plans to earn an associate's degree. He had the help of Calderon, his parents had been paying taxes for over a decade, and he got good grades, so he was able to secure a scholarship. The scholarship covers tuition and his family is responsible for paying for books.

Even with a fully funded trip to college, Marco still faces obstacles. He'd like to be able to help his parents out but can't work because he doesn't have a Social Security Number. He wants to get a bachelor's degree after he finishes his associate's degree, but doesn't know if a four-year university will offer enough scholarship money. Even public universities can be prohibitively expensive for a student who can't access loans. Because of his disability, Marco relies heavily on his parents. If he were offered a full scholarship at an out-of state university, he wouldn't be able to go. This isn't uncommon, according to Julio. He's observed that undocumented students are more likely to stay close to home. He adds that "the students who do get scholarships to attend college away from home often end up dropping out because they can't afford to cover extra costs like food and living expenses, even if they're working full-time."

It is estimated that between 65,000 and 80,000 undocumented students who have lived in the United States for 5 years or longer graduate from high school every year. During the 2014-15 school year, the first year of HB 851's implementation, 2,475 students attending 31 Florida public colleges and universities used the bill's tuition waiver for students without legal residency status. Statistics show that 76.8 percent of eligible students attended Florida College System institutions, compared to 23.2 percent of students who went to State University System of Florida institutions.

The Situation Faced by Students Who Don't Qualify for In-State Tuition

Not all undocumented students are as lucky as Marco. Individuals who don't qualify for HB 851 are forced to pay out-of-state tuition fees, which are often an enormous financial burden to students and their families.

One student in this situation is Marie, a young woman from Haiti whose motivation in traveling to the US was to get a bachelor's degree in chemical engineering and then return home to Haiti. Her parents are paying $10,000 a semester to send her to community college in Florida. In 2012, Marie and her sister were granted tourist visas to the United States. Her sister was in Mexico, so she decided to meet her there before they traveled north to the US together. Their plans got derailed when their papers were stolen from a car in Mexico City. Instead of going back to their hometown in Southern Haiti, they decided to make the trek to San Diego via Aguas Calientes and Tijuana. As soon as they crossed the border, they were apprehended and sent in separate directions: Marie was a minor so went to an immigration detention center for children, and her sister went to one for adults. Now, both sisters remain in the country: Marie is undocumented and her sister was able to get Humanitarian Parole, which allows her to legally work in the US and qualify for in-state tuition. Her parents pay $2,000 a semester for her to attend community college, $24,000 a year for both daughters. They may have to sell their house if Marie wants to continue getting an education.

Marie entered 12th grade at a Florida high school in August 2013. At the beginning of the year, her goal seemed far away, given that she was undocumented and enrolled in a high school where she was expected to speak, read, and write in English. However, by the end of the year she had taken the AP French exam and three college-level courses, and passed the FCAT, the exit exam for Florida seniors. For the most part, Marie was reserved and found it difficult to make friends with her peers; however, she was able to forge a relationship with a teacher, Sherley Louis. Sherley said that while there are plenty of resources for students seeking guidance on navigating the college process, many students, like Marie, don't use them.

Marie settled on her current college because of cost. She only completed 12th grade in the US, so she does not qualify for the HB 851 waiver and therefore has to pay out-of state tuition. She's finishing her associate's degree in December and is eager to continue her education at a four-year university. She was recently accepted to two out-of-state universities, and is still waiting to hear back from a couple of schools. One of them offers full scholarships.

A Lack of Support in Navigating the College Application Process

Many students and families feel lost when it comes to applying for college. Some high schools have supports to help guide students through the process, but not all have access to them.

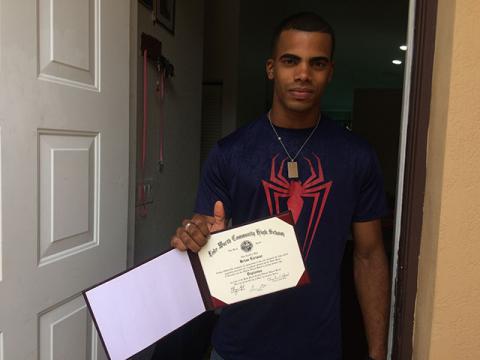

One of the many students who struggled with this process is Brian, a Lake Worth High School graduate in Palm Beach County, Florida. In order to fulfill the community service requirement at his high school, Brian spent hundreds of hours volunteering at the Guatemalan Mayan Center, a few blocks from his house. He arrived in Lake Worth, Florida, from the Dominican Republic in the early 2000s when he was nine. He took Portuguese classes, ran track and was in the ROTC. When he finished high school, his mother enrolled him in DACA. "That got me to where I am now," he says. "I got my license, my Social Security, the permission to work in the US. If it wasn't for Obama, I wouldn't have all my papers."

Brian wants to be a police officer, but in Palm Beach County, Florida, you have to be a US citizen to be a cop. He plans to join the Marines, but chose "to go to college, then focus on the Marines." He first tried to enroll in the Hollywood Institute's barber program. Annual tuition and fees total $17,815 and the only financial assistance available is through federal loans or Pell Grants. Since students with DACA don't qualify for federal financial aid, Brian had to forego the program. Instead, he enrolled in Palm Beach State College where he was accepted into the Post Secondary Adult Vocational program. He's received a certificate in welding, a program that doesn't require a GED or high school diploma, which Brian has. Although he qualifies for the HB 851 waiver, Brian didn't learn about it until it was already too late. He's been paying out-of station tuition, about $700 a semester, and has had to work two jobs to do so. He hopes to take advantage of the waiver next semester.

College Affordability in the Context of Immigration

Some universities are offering a low-cost path to college for immigrant students. Will it catch on in this age of escalating anti-immigrant sentiment? Or will the financial support that exists now vanish?

In some ways, Brian is the luckiest of the three students profiled here, but he either didn't have or didn't engage with the proper supports in high school that could help him apply for the in-state tuition waiver and enroll in an academic track in community college.

Marco was fortunate enough to receive a full scholarship to college, but according to the College Board report Young Lives on Hold, "The vast majority of private scholarships apply federal standards and therefore deny assistance to undocumented immigrants."

Many undocumented students spend high school assuming that they will go to college. Andres Ramirez says that when they get to the end of senior year, when everyone is finalizing plans for college, "They realize that their situation is different. They never think about the fact that they actually cannot go to college." And then, "There are some others that don't even consider college because from the very beginning they knew that it was going to be very difficult."

While most of the national conversation around college affordability centers around student loan debt, it leaves out a large group of people who are unable to get student loans in the first place. In states like Georgia, undocumented students are forbidden from attending large public universities like the University of Georgia or Georgia Tech.

Most universities will accept undocumented students, but won't provide them with the financial assistance they need. Prestigious private colleges like Amherst, Tufts, Emory, Swarthmore, Wesleyan and Yale have introduced need-blind admission policies for undocumented students, but they only accept a small percentage of the students in search of a college education. In September, Brown University also joined this group by announcing that the school will soon meet 100 percent of each student's financial need upon enrolling regardless of immigration status.

Of the 65,000-80,000 undocumented students who graduate from high school each year, only 5-10 percent enroll in college. Even fewer graduate. Roberto Gonzales, the author of the College Board report, argues that if we continue to make it difficult for immigrants to access higher education, "we could lose a generation of promise and in the process run the risk of dragging down entire communities." He goes on to say that getting a college degree enables undocumented immigrants to "enhance the nation's social and economic security." This generation of promise could all but disappear if Donald Trump follows through with his plans for mass deportation of undocumented immigrants.

In the days following the election, colleges such as University of California, Brown, Yale, University of Wisconsin-Madison and Harvard have rallied around their undocumented students, proposing ideas like a sanctuary campus. A sanctuary campus, like a sanctuary city, would refuse to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement, thereby protecting undocumented immigrants from law enforcement. Trump has denounced sanctuary city policies and has threatened to cut federal funding. If enacted, those cuts could extend to federally funded grants and scholarships for college students. It's unclear how President-elect Trump's policies on immigration will affect current or prospective college students. However, it is clear that students and faculty around the country are uniting together to show how integral undocumented students are in the social fabric of their schools.

Note: The names of the students interviewed in this article have been changed to protect their safety. This report received support from the Institute for Justice and Journalism.

[Lena Jackson is an independent filmmaker and teacher. She has traveled to Haiti, India, Guatemala, Cuba and Zimbabwe working on videos for Fusion, Medium, PBS's EarthFix, Nomadic Wax, Sesame Workshop India, Cultural Survival and Cuba Skate. She holds a BS in foreign service from Georgetown University and an MA in documentary film from the University of California, Santa Cruz.]

Copyright, Truthout. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission.

Truthout publishes a variety of hard-hitting news stories and critical analysis pieces every day. To keep up-to-date, sign up for our newsletter by clicking here!

Spread the word