Following the massive Women’s March and the surprising partial success of protests against Trump’s immigration ban, many feel that the logical step is to escalate. Seize the momentum, put more pressure on the administration, disrupt and paralyze as much as possible. I feel it myself. There are ways in which there is more possibility in the air than there has been in a long time, and Trump has wasted little time going about his authoritarian business.

That, no doubt, is the reason why the idea of calling for a general strike – a general national strike – has caught the imagination over the past few days. After Francine Prose put the idea out in the Guardian, it spread rapidly throughout social media, and split into multiple proposals and counter-proposals.

Some, including Prose herself, see themselves carrying on in a venerable tradition of mass social disruption. But, as much as these proposals look like a natural response to the moment, they are severely disconnected from reality. Calling for a general strike now bears no relation to what mass strikes have meant in the past. The flight from reality shows up in activists’ blasé attitude to history and their very distant relationship to the working class.

The United States has the most violent labor history of any major industrial country. General and other large-scale strikes in the US have nearly always been met with major repression, from police, National Guard, even federal troops. For instance, the general strike in San Francisco of 1934, which developed out of a longshoremen’s strike, led to running battles with the police and a number of deaths.

The massive strikes in the period of 1919-1922, involving more than 1 million workers in industries like railroads, steel and mining, were met with enormous violence. One of the most famous is the coal mining wars, which culminated in the Battle for Blair Mountain. It pitted armed and organized miners against a private militia, federal troops, bombing runs by employer-hired aircraft, and some of the first post-war uses of military planes. Hundreds of miners died in the battles.

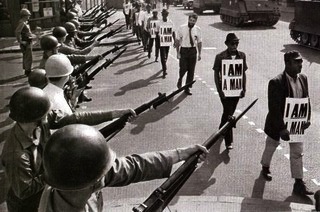

During the Ludlow Massacre, National Guardsmen mounted a machine gun on a train, and mowed down strikers and their families living in tents.

Machine gun nest at Ludlow

During the massive Pullman Strike of 1894, during which Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs was arrested, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike, and the Attorney General carpeted every state from Illinois to California with injunctions and martial law. Federal troops aided local police and private guards to suppress the strike.

We can tell similar stories for the suppression of the Great Strike of 1877, which included a general strike in St. Louis; for the strike wave of 1886; for the Lawrence strike of 1912; for the Little Steel Strike, Harland County strikes, the Auto-Lite Strike, the Minneapolis strike, and the textile strikes of the 1930s; and so on and so forth.

This isn’t just distant history.

On March 10, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. addressed “Local 1199,”* a radical local of drugstore and hospital workers, and spoke about the need for organizing the unorganized and for a trans-racial class alliance against exploitation and imperialism. Turning his attention to African-American sanitation workers striking in Memphis, Tennessee, he said, “You may have to escalate the struggle a bit….just have a general work stoppage in the city of Memphis.” Less than a month after calling for a citywide general strike, King was assassinated in that very city.

During the Hormel Strike of 1984-5 in Austin, MN the National Guard helped local police forces suspend civil liberties, impose deeply oppressive labor law, and undermine the strike.

The more seriously disruptive the strikes, the more dangerous they are. It is no doubt true that the American state has reduced its readiness to violently repress workers. But even that is as much a function of the decline in worker militancy itself as it is a more tolerant view of major strikes.

Even when not violent or repressed, strikes are serious business. They are often lost, and if strikers aren’t injured they can lose their jobs, friends, and even families. The law is pitted heavily against workers – they can be replaced, they lose free speech rights when at work, even the whiff of strike activity allows employers to shut down the entire factory, and legal protections of workers are poorly enforced. The police and the rest of the security apparatus are usually happy to enforce that law, and there is often no way for workers to carry out a proper strike without breaking those laws. To the degree we have forgotten this, it is because worker militancy has declined, strike rates are way down, and union memberships have dwindled into the low single-digits.

In the past, workers stayed out on those strikes, even fighting the state, in part because of dense, historically developed, cultures of solidarity; established traditions of militancy; organized, if not always recognized, unions; and long connections with left-wing organizers. These days, the appetite for fighting the state is next to nil, there is no tested public sympathy for labor actions, and there are no clear organizations standing ready to lead.

If you’re going to ask people not just to risk losing their jobs but potentially face the armed apparatus of the state, there had better be preparation, leadership, and some evident readiness for mass labor actions.

Not to mention, there had better be a recognizable goal. But what is the point of the proposed general strike? To say down with Trump? What, so we can have Pence?

Or is the point just a generalized ‘No’? A massive expression of discontent? None of the significant costs of a general strike are worth it if it’s just a grand gesture of refusal.

On one version, the point of the strike is to affirm a grab-bag of demands: no to the immigration ban, yes to universal health care, no to pipelines, no to global gag rule and, inexplicably, a final demand that Trump reveal his tax returns. These demands show no evidence of thinking about what the immediate interests of workers might actually be – no mention of proposed national right-to-work legislation, $15 minimum wage demands, or even Trump’s terrible Labor Secretary pick. Trump’s nationalist and deeply inegalitarian economic ‘plan’ at least acknowledges the need to address bad employment prospects and stagnant wages.

It would be reasonable for workers to dismiss the call for a general strike. It looks like they are being asked to be actors in someone else’s drama, by people who just cottoned on to the fact that things are shitty out there.

Moreover, even moderately effective general strikes don’t emerge, willy-nilly, like miraculous interventions into national life. They are intensifications and radicalizations of already existing patterns of resistance by the working class. This demand for a general strike looks less like that intensification and more like an attempt to leapfrog all the hard, long-term political work that goes before.

At least some of those arguing for the general strike seem to sense that there is an element of bad faith here. For instance, Francine Prose added the qualification, which I have seen repeated in a number of places, that only those “who can do so without being fired” should go on strike. This must be the first time someone called for a general strike but exempted most of the working class.

Believe me, I’d love to see a real general strike, a serious attempt at restructuring society, not just lopping the head off the Republican hydra. But there is no royal road to revolution, or even to a true mass movement for social change.

Alex Gourevitch

* The original post said “SEIU Local 1199,” but Local 1199 only joined SEIU many years after MLK addressed them.

Spread the word