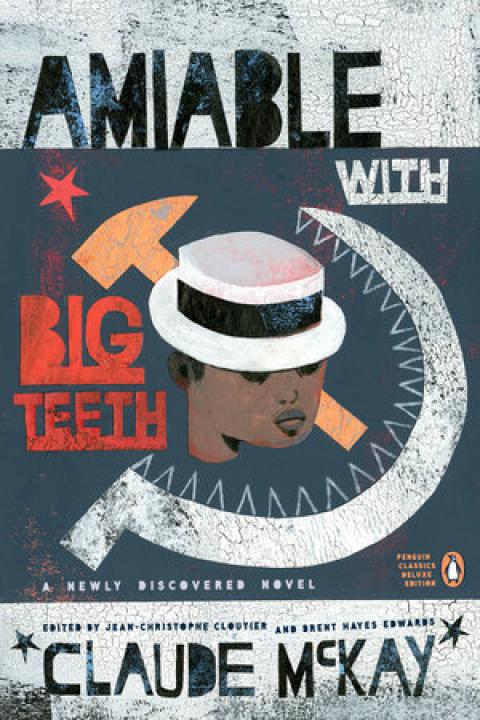

Amiable With Big Teeth

By Claude McKay

Penguin Classics

ISBN 9780143107316

"I wonder if I understand you rightly," the Ethiopian prince Lij Tekla Alamaya asks his American friend Gloria Kendall. "Slavery in the Bronx, New York, in the most highly civilized city in the world?"

"I will take you to see it with your own eyes," Gloria replies. "There are over half a dozen blocks in the Bronx where starving colored women sit and wait for white women to come and buy them to work at ten cents an hour. Ten hours of lugging and scrubbing down on their knees to make one dollar. We call it the Bronx Slave Market, for the black women line up there and wait for the white mistresses just as the slaves down South waited for the masters to come and buy them."

This provocative exchange, one of many in a novel by the Jamaican-American writer Claude McKay, would have jarred the conventional readers of his day — had they ever seen it. Not a word of the novel, though, was read by any member of the public until last month, when Amiable With Big Teeth was published by Penguin Classics, nearly seventy years after McKay's death. The novel's arrival was an extraordinary event in the literary world for a couple of simple reasons: It's exceedingly rare for a completed, relatively unblemished manuscript to emerge from hiding at all, and the discovery of this one alters long-held perceptions of McKay's canon and life in Harlem during the lush period between the two world wars, when popular belief held that the Harlem Renaissance had petered out with the onset of the Great Depression.

"It's a really remarkable book," Jean-Christophe Cloutier, the academic who unearthed the McKay manuscript, told the Voice. "It's a contemporary novel in a strange, belated way."

McKay, an icon of the Harlem Renaissance, wrote poetry and fiction, and is probably best remembered for Home to Harlem, his 1928 bestseller, and the crackling sonnet "If We Must Die," a defiance of racial subjugation. After 1933, when his novel Banana Bottom appeared, scholars believed McKay had turned his back on fiction writing. He never published another novel while he was alive.

In the summer of 2009, Cloutier was an intern in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University, where he was studying for his Ph.D. An admirer of Samuel Roth, the literary pariah known for challenging obscenity laws in the United States, Cloutier was sorting through more than fifty boxes of Roth's papers when he discovered a 300-page, double-spaced manuscript in a "do-it-yourself" black binder.

The cover bore McKay's name and the title of the novel.

"It was surprising and wonderful, but at the same time I wasn't hubristic enough to believe [it was authentic]," Cloutier, now an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, recalled. "No one had heard of it."

Cloutier took his discovery to Brent Hayes Edwards, his dissertation adviser and an expert in black literature. Despite his thorough knowledge of McKay's life and work, Edwards didn't know of any lost novel. No McKay biography referenced it.

"Could this be a hoax? A forgery?" Edwards, a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia, wondered at the time. "It seemed a little much, to have written a 315-page forgery and not done anything with it."

Edwards had reasons to believe the manuscript, a satire concerning the fervor in Harlem over Fascist Italy's invasion of Ethiopia in the mid-1930s, was legitimate. Uproarious and polemical, Amiable takes dead aim at Communism, skewering the radical leftists who McKay believed exploited blacks for their own selfish ends. The novel also references real-life figures like the labor leader Sufi Abdul Hamid, who was prominent in McKay's time, and uses the term Aframerican, a description McKay employed for blacks from the Western Hemisphere.

But to actually authenticate the manuscript was a painstaking, years-long process. Edwards, familiar with McKay's handwriting, analyzed corrections scrawled in the margins. With Cloutier, he hunted for references to the lost novel in letters; together they traveled to archives at Indiana University; Emory University; Yale; Washington, D.C.; Texas; and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem.

The big break came when Edwards discovered a correspondence between McKay and his friend Max Eastman, a writer and political activist who was a prominent patron of the Harlem Renaissance. McKay and Eastman referenced a novel-in-progress that was clearly Amiable — in one letter, Eastman praises a simile found, word for word, in the newly discovered manuscript.

The letters revealed McKay had been hard at work on the novel in 1941, though the archival trail soon runs out; the two scholars believe McKay's publisher, E.P. Dutton, rejected it, and the self-professed "vagabond poet" lost track of the manuscript. At around the same time, his health began to fail him.

To read Amiable today is to discover a lost world that, with its internecine struggles over race and class in New York and elsewhere, may seem equally alien and visceral. Once infatuated with Communism, like many leading black artists of his day, McKay furiously rejected the doctrine later in life. But unlike other converts to the anti-Communist cause, such as his friend Eastman, McKay didn't suddenly celebrate free markets.

Rather, his enmity was grounded in the way he saw left-wing, predominately white leaders exploiting disaffected blacks for their own internationalist purposes. "Let's drink to the Aframerican minority and its conquest by the Popular Front," says Maxim Tasan, Amiable's Communist archvillain.

In the novel, Italy's invasion of Ethiopia rallies Harlemites to the African nation's defense, but quickly divides them along political lines. Alamaya, the Ethiopian prince, arrives in Harlem to try to rally support and resources for his beleaguered nation. Hands to Ethiopia, a group led by a Democratic power broker in Harlem named Pablo Peixota, is set up to aid the effort, but soon it's countered by Tasan's White Friends of Ethiopia, an explicitly leftist collective that dismisses all Soviet skeptics as Fascists and Trotskyites.

The freewheeling burlesque rambles through cocktail parties, nightclubs, and churches, culminating with a murder by men in leopard suits. Harlem in the 1930s is as scintillating as it was in 1920s, infused with a cosmopolitan vigor that makes you nostalgic for a time you can never truly know.

Blacks march against Fascism outside Italian restaurants. Young men who "rouged their cheeks like the girls" frequent the "bawdiest bar" on Lenox Avenue. A flamboyant "professor" without a degree is the unlikely hero, reminiscent of the black bibliophiles who were the beating heart of the culture.

Dorsey Flagg, McKay's proxy in Amiable, elegantly fights back against the way a black artist paints racist caricatures of his own.

"We need Raphaels to picture the mothers of the race with their children," Flagg says. "Millets to show us black workers in the field and Gauguins to paint the exquisite beauty of brown flesh."

If Amiable can feel wooden at times — characters become mouthpieces for ideas McKay craved to hash out as bluntly as possible on the page — and overly didactic, the novel is an essential window into an overlooked era, when turmoil in Europe and the Depression at home didn't stop Harlem's brightest lights from carrying on with their work.

"There's this potted narrative: Things fall apart and wind down. But a writer is just like a musician or a painter or a dancer," Edwards said. "You don't stop doing your work because it's an economic depression. You're still thinking as an artist."

Spread the word