A Soviet Disco Excursion (2016); The Soviet Tape (2015), curated by Fulgeance and DJ Scientist, available on vinyl, CD and download from https://thesoviettape.bandcamp.com/

Disco Wave from Russia and Eastern Europe, curated by Mr. Bongo, Vinyl Factory Records 2017

A specter is haunting the American liberal public: the spectre of Vladimir Putin busting a move.

Accused by a range of liberal public figures of masterminding a plot to elect Donald Trump to the presidency, Putin looks and acts the part, like a “bad guy” in an eighties Hollywood film – all the while cultivating friendships with “good guy,” Steven Segal. Perhaps reflective of his days as an intelligence officer based in East Germany between the rise of Gorbachev and the fall of the Berlin Wall, Putin is enamored with the action aesthetic of the Reagan years. His calm “bad guy” veneer evokes the likes of F. Murray Abraham or Robert Shaw. But Putin came of age at the dawn of the 1980s in Leningrad, and he more likely gyrated frenetically to Boney M and Giorgio Moroder in the city’s discotheques as a young KGB agent. After all, in Soviet Union, disco danced you.

The origin of the Soviet disco tradition, one that lasts to this day in the DJ-laden nightlife of Moscow and St. Petersburg, lay in the Stalinist era. Western culture – modernism, cubism, rock and roll, all that good stuff – was “decadent,” perhaps even a plot by Trotskyists or the Western intelligentsia to dull the steely nerves of the Soviet people. But dancing – this was a-OK. Block parties with an accordion player gave way to gramophones then replaced by turntables, and later, the discotheque. Struck by the popularity of the discotheques, creative commissars attempted to harness the phenomenon: to bring people out to party events and provide a source of fun after hours of speeches about grain, the world market, five-year plans and the specter of nuclear war. Thus, the emergence of the “official disco.”

Championed by the Communist Party’s youth wing, the Komsomol, official discos transformed drab party auditoriums into festivals of transgression. With a four-to-the-floor beat, gyrating Soviet bodies experienced the dialectic of syncopation and rupture expressed in the best disco music – usually themed by some aspect of the party line: celebrating International Women’s Day or physical fitness. The best DJs from these party events landed gigs at the more exclusive discotheques, usually housed in the Intourist hotel chain and frequented by the likes of Putin and his jet-setting KGB comrades.

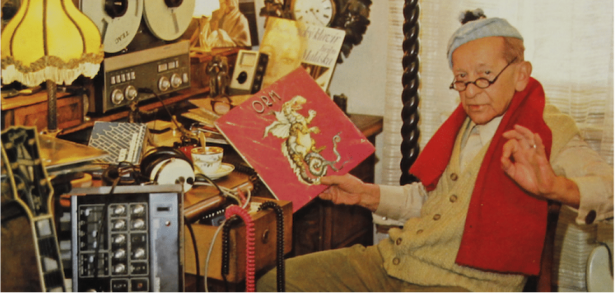

Yet the heart of Soviet disco, under the guidance of the increasingly autonomous Komsomol, beat not in exclusive hotels, but in dormitories and union halls, in makeshift events where often, due to the cost of vinyl, the wheels of steel were replaced by a set of reel-to-reel tape decks. DJs transformed limits into creative innovation and replaced the wicka-wicka with the quick sound of spooling tape.

Soviet disco developed as a form in its own idiosyncratic ways, increasingly distinct from popular foreign – mostly Scandinavian and West German – imports. Unlike the robotic Linn or Roland 808 drum machines which had begun to dominate disco and dance music in Europe and North America, early Soviet disco featured the lush sounds reminiscent of the Philadelphia sound, or Chicago house music, and the lead instrument was often a flute or a Hammond organ. A slight Turkic inflection accompanied a polyrhythm – a drummer playing four-to-the-floor, while congas or bongo drums played “on the twos.” DJs built their own synthesizers from stolen goods and old computers and late in each track, there would be a “break,” where Soviet DJs mirrored hip hop and house DJs in Chicago and New York, they melded them with other songs and created their own mixes on the fly. To be expected in a nation that produced the theremin.

Despite its idiosyncrasies a musical form, Soviet discos became a foci for an emerging Soviet counterculture which built on a broad set of international connections. What began as permissible disco – think Boney M – branched out in many different directions. The disco-classic rock hybrid of the Steve Miller Band’s “Abracadabra” opened the way, in the midst of the dreary Brezhnev years, for broader appreciation of rock music. Some disco nights even featured talks by Komosol members on American or British rock music, especially virtuoso prog-rockers like King Crimson or Yes. Meanwhile, the 1980 Summer Olympics aimed squarely at the Soviet disco audience and selected “Moscau,” a track by West German disco star Dschinghas Khan for the Games’ television theme song.

One of the most unique forms of Soviet disco in the 1980s came from Zodiac, a Riga-based band whose “space disco” in many ways prefigured Daft Punk. Much like the Parisian purveyors of ‘electronica’ distilled the cybernetic utopianism of the late 90s, Zodiac’s space disco distilled an earlier worldwide interest in computerization and its relationship with intergalactic voyages. Indeed, Zodiac scored a documentary on the Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, which illuminated the close relationship developing between the Soviet space program and the purveyors of the “spacey” disco music, with its bleeping interstellar synthesizers. Most of Zodiac’s songs have no lyrics, save for chants of “DISCO.” Argo, another Soviet disco act, produced music as spacey and strange as it gets, with a sound intrinsically informed by vinyl records like Brian Eno’s collaboration with David Byrne that likely circulated through underground commerce in the Intourist Discotheques.

Perhaps the strangest Soviet disco sounds, however, were official Soviet records ostensibly dedicated to aerobics or exercise, and put out by the state-owned Melodiya label. These rabbit holes of synthesized funk were snuck past censors by cheeky bureaucrats claiming they were for exercise. To an extent, the image is a metaphor for the closing years of “really existing socialism,” the rationalization of bodies moving in unison being the outer shell of the actuality of bodies freely and frenetically moving, like Putin on the dancefloor. Sure, Americans obsessed with their VHS machines danced in front of their television sets to the lead of Jane Fonda or Richard Simmons, but the phenomenon couldn’t compare with Soviet iterations of the same thing: absolute space-funk, robotic voices, screeching flutes played through wah-wah pedals. A disco super-structure with a good and thumping bass. (Sorry/not sorry.)

In the dreary years between Brezhnev and Gorbachev, from the late seventies to mid eighties, young party members of the Communist Party, however removed from the classical Marxist tradition, found freedom in the necessity of mobilizing party cadre. They chose disco because – well, it was fun. Like Studio 54 in New York City. American, but not American like Reagan and the atom bomb. Disco evoked a different America: dancing, good times, losing oneself in the groove of syncopation. It allowed Soviet youth to build their own America, a non-place of beats and melody, bass and space.

The story of Soviet disco is the story of how dance music developed everywhere across the seventies. As traditional instruments became inaccessibly expensive, DJs made their own mixes and synthesizers became common. But Soviet disco fits in another story too. Beyond its officially recognized and promoted role – often in and around the promotion of physical activity – it has a deeper genealogy in the pre-Stalin glory of early Soviet cultural production.

The legacy of 1917 could indeed be carried out, so thought its practitioners, in particular the dedicated space disco of Zodiac, by bleeping synths and pounding polyrhythms. It may not have been fully luxury but it certainly was automated “communism.” The idea that a cultural producer would take the responsibility not merely to make bodies move on the dance floor, but to further the great legacy of non-capitalist, dialectically elegant art of the early Soviet avant-garde may seem distant, and contradictory to our understanding of the late Soviet Union as a highly repressive society. But an expression of the possibility of other worlds in Soviet disco was intrinsic to the role it played, both in the history of dance music, but also in the history of Soviet culture. It retains its charm not merely by being kitsch, but is every bit a legacy of Soviet culture as are the films of Tarkovsky. And unlike the ‘high art’ of Tarkovsky, one can indeed imagine Soviet people from all walks of life, including of course, the happy-go-lucky Putin, letting their regimented bodies go loose and wild on the dance floor. As DJs continue to dig in the crates for new textures for their sonic tapestries, let’s hope for a deeper revival of Soviet disco music.

Many of the songs mentioned in this article are available for listening at this YouTube playlist: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pJ4gH86DKPo&list=RDpJ4gH86DKPo&t=13

This piece appears in our fourth issue, “Echoes of 1917.” Order a digital copy.

Red Wedge relies on your support. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a subscriber, or donating a monthly sum through Patreon.

Jordy Cummings is a critic and labor activist and member of the Red Wedge editorial collective. He recently completed his PhD at York University in Toronto.

Spread the word