In “No Good Read Goes Unpunished,” the 633rd episode of The Simpsons, the longest-running scripted series in TV history finally acknowledged that there is something problematic about the way it has portrayed Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, owner of the Kwik-E-Mart, for the past three decades. Yet at the same time, the show managed to continue taking no responsibility for its tone-deafness on the matter. If the episode didn’t quite do what Bart Simpson would have done in season five, episode 12 — i.e. say “I didn’t do it” — it certainly implied that nothing can be done to make Apu less of a stereotype now.

The scene that addressed Apu prompted a lot of blowback online today, including some, not surprisingly, from Hari Kondabolu, the comedian and maker of the 2017 TruTV documentary The Problem With Apu, which thoughtfully considers the ramifications of Apu’s often one-dimensional depiction. But last night’s Simpsons installment doesn’t just underline the issues that still surround Apu. It magnifies the struggles that The Simpsons faces as it nears its fourth decade of existence on Fox.

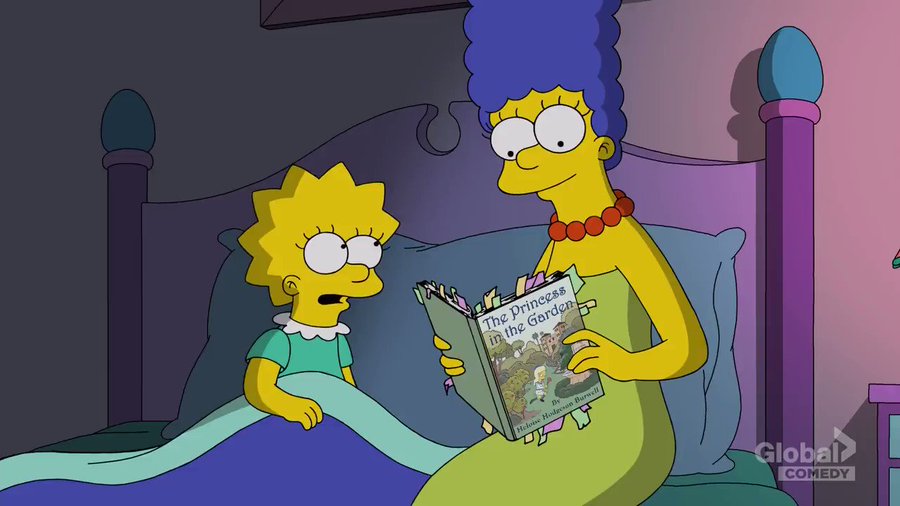

For context, here’s what happened in the episode. While Marge attempts to introduce Lisa to one of her favorite books from childhood, The Princess in the Garden, she realizes that it is filled with racist and horribly regressive language. Embarrassed and guilt-ridden, she has a dream in which she speaks to the book’s author, Heloise Hodgson Burwell, and gets the green light to revise the text. Marge does a rewrite and turns the story into the tale of a “cisgender girl” who is fighting for wild-horse rescue and net neutrality. “It takes a lot of work to take the spirit and character out of a book, but now it’s as inoffensive as a Sunday in Cincinnati!” she says, while Lisa notes disapprovingly that in the new version, the protagonist can’t go on an emotional journey because she’s already “evolved” from the very beginning.

“Well, what am I supposed to do?” Marge asks. (Either don’t read Lisa the book, or read her the book as is and discuss why the problematic things in it are problematic? I don’t know, these are just ideas.)

That’s when the conversation turns to Apu. “Something that started decades ago, and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?” Lisa asks. Then she looks at a signed photo of Apu that’s sitting on her nightstand.

“Some things will be dealt with at a later date,” Marge responds cryptically.

“If at all,” adds Lisa. Then mother and daughter stare into the camera blankly as if they’re being held hostage by their own cartoon.

“How much of that do you actually believe?” Marge asks skeptically. The professors indicate they buy into most of it, but when Marge asks them how they “deal with it all,” whatever that means, they respond simply by guzzling hard liquor. And that’s the end of that story line.

There are many disappointing things about the way this all plays out, many of which have been noted by NPR’s Linda Holmes in this smart piece, including the fact that equating The Simpsons with what is, in this episode, an extremely old piece of children’s literature by a dead British lady, is false on its face. As Holmes points out, the show also missed an opportunity to acknowledge, as Kondabolu’s documentary does, why the depiction of Apu and his portrayal by a white man, Hank Azaria, have been offensive to many members of the South Asian community, who had very little representation on prime-time television until quite recently.

For people like myself who adore The Simpsons — I still say it’s my favorite show ever even though it now has amassed more so-so seasons than ones that were consistently brilliant — this episode is frustrating because at one time, I do think it would have tried to wrestle with these issues in a far more astute, surprising, and funny way. Many parents in America have found themselves in the position Marge does in this episode: excited to share some once-beloved book, film, or TV show, only to discover that it looks very dodgy in the light of 2018. At first I was delighted to see The Simpsons offer a take on this, but as written by Jeff Westbrook, “No Good Read Goes Unpunished” — a title that has a defensive air about it from the get-go — just brings up a bunch of stuff and expects to win points for doing so without actually truly reckoning with any of it.

It also betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of its characters, at least as they were originally envisioned. When Marge reads a line in The Princess in the Garden that refers to South Americans as “naturally servile,” Lisa asks, “Mom, why’d you stop reading?” instead of doing what, in my mind, she would more likely do: balk at that choice of words and force her mother to question why she liked this book in the first place. This episode would have made a lot more sense as a Simpsons episode if Lisa had been the one trying to understand who Heloise Hodgson Burwell was and making her mother see why the book was problematic, the same way she once tried, to no avail, to open the eyes of her fellow Springfieldians to the troublesome overlooked history of Jebediah Springfield.

Perhaps part of the problem is that The Simpsons has been on for such a long damn time, well past long enough to lose its own sense of identity. When it first dominated the pop-culture landscape in the early 1990s, a lot of the show’s appeal stemmed from its skillful and fearless tendency to jam its thumb in the eye of the American Establishment, by highlighting white male laziness via Homer, the crass privileged class via Mr. Burns, and a whole host of other marks of ignorance — from sexism to intolerance of vegetarians — via the crusading Lisa Simpson, the show’s perpetual 8-year-old voice of reason. For all of the stereotypes he has embodied, even some of the jokes generated by Apu actually pointed a finger at the abhorrent attitudes that Indian-Americans have to tolerate from their Caucasian counterparts. (“Please feel free to paw through my Playdudes and tell me to go back to some country I’m not actually from,” Apu tells Homer in season 16.)

Even though The Simpsons still makes a sport of mocking our culture, when you’ve been on the air for nearly 30 years, it’s hard to come across as the rebellious outsider sticking it to the man, especially on a show that has been largely written by white men, many of whom graduated from Harvard University. (Ironically, last night’s episode of The Simpsons was broadcast minutes after a 60 Minutes segment about the Harvard Lampoon, which featured longtime Simpsonsshowrunner Al Jean explaining that he tries not to specifically recruit Lampoon alumni because he wants more diversity in the writers room.) One could argue that The Simpsons is now the Establishment, and has been for a while. Once you become the Establishment, there is a tendency to become lazy and complacent, while also feeling fiercely defensive of one’s legacy. In my view, that combination of factors plays a key role in the show’s inability to fully own up to the Apu problem.

In The Problem With Apu, former Simpsons writer and producer Dana Gould admits to Kondabolu that, “I think if The Simpsons were being done today, I’m not sure that you could have Apu voiced by Hank.” But here’s the thing: The Simpsons is still being done today. Because other TV shows have not lasted this long, they have never been forced to course correct and deal with their own insensitivities in the same way that The Simpsons must. If, say, Seinfeld were still on TV, it would be struggling with the same issues. (Writes on chalkboard à la Bart Simpson: I will not go off on a tangent about Babu Bhatt. I will not go off on a tangent about Babu Bhatt.)

What can The Simpsons do about its Apu problem? Actually, a lot of things. For starters, it could hire more South Asian writers, or at the very least consistently consult with some on matters related to Apu if its staffers haven’t started doing that already. While Azaria is a great talent, if it’s true that The Simpsons wouldn’t enlist him as the voice of Apu today, then make a switch and hire an Indian-American actor to voice him. That sort of switch might breathe some fresh, unexpected air into a character that has been publicly shamed for not changing with the times.

In his interview with Kondabolu, Gould rejected the idea of getting rid of Apu entirely, but also of nixing his job at the Kwik-E-Mart. I’m not sure why the latter is such an unreasonable idea. Over the course of The Simpsons’ run, Homer has been a nuclear power plant employee, the Springfield Isotopes mascot, an astronaut, an adult-education instructor, a food critic, a blogger, the owner of his own snowplow business, and about 30 other jobs. Is it so crazy that Apu might decide to retire from the Kwik-E-Mart to pursue some other line of work and just stick with it for the rest of the show’s run?

The idea that anything should be perceived as out-of-bounds on an animated show that is known for its silliness and boundary-pushing seems like stubbornness more than anything else. I say that, too, because The Simpsons almost shut down the Kwik-E-Mart two seasons ago, in the episode “Much Apu About Something,” in which the convenience store was destroyed, rebuilt as a much healthier Quick & Fresh and co-run by Apu’s nephew Jay, voiced by Utkarsh Ambudkar, who discusses the episode in The Problem With Apu.

Not surprisingly, the Kwik-E-Mart goes back to being the Kwik-E-Mart by the end of that half-hour. Before that happens, and just after Apu is exposed to the sight of the Quick & Fresh, the Azaria-voiced clerk hugs a large printed replica of the Kwik-E-Mart as it used to be. “I will just live in the happy past one moment longer,” he says, clinging to the image, which has been re-created to scale, as it wheels him off a cliff. “Disco Stu is in denial with you,” shouts Disco Stu, who is also flailing in the air of nostalgia, getting ready to crash.

That scene is the perfect metaphor for The Simpsons today. It’s a show that, reputation wise, is still living in the happy past and clinging to its Kwik-E-Mart, not listening while others shout about being in denial.

Spread the word