This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story, by Scott Gordon, originally appeared on WisContext, a service of Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, and University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension.

Editor’s note: Six days after this story was first published, the state of Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources approved an application by the city of Racine to withdraw water from Lake Michigan to supply a Foxconn LCD screen factory. The legal issues discussed in the story may remain a matter of contention in Great Lakes water policy.

Community members and advocacy groups opposing the bid by Foxconn and the city of Racine for Lake Michigan water are zeroing on a specific issue: The request amounts to a water utility sourcing the Great Lakes almost entirely for the use of one private company.

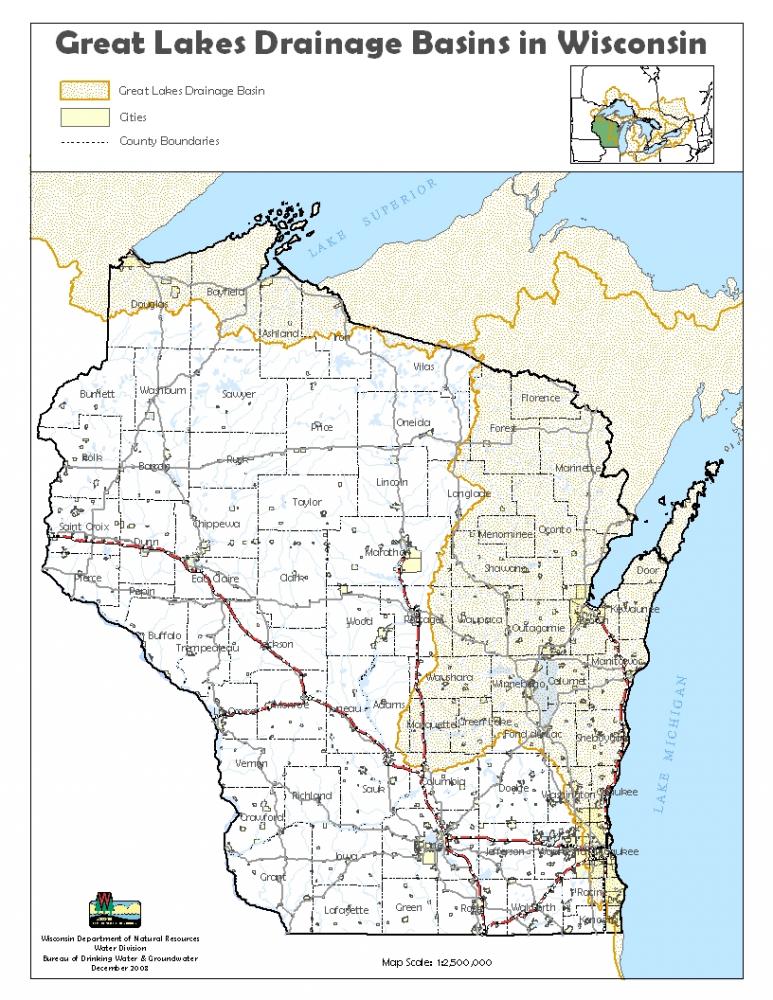

Public water utilities serve industrial customers all the time—Racine currently has about 40—yet Wisconsin is confronting the inherent tension of fueling a private for-profit operation with a water resource that is protected as a public trust and governed at state and regional levels. Under the regional water-use agreement known as the Great Lakes Compact, a public utility can pump the lakes’ water to a location that straddles the line of their drainage basin, as the site of the Foxconn factory does. Sending these waters to such a location that straddles the Great Lakes Basin is called a diversion, and in this case requires Wisconsin authorities to review the proposal and decide whether or not to allow it to proceed.

The language of the Compact emphasizes that public water utilities are largely supposed to serve residential customers, while also acknowledging the reality that they also serve businesses. The Racine Water Utility is looking to sell 7 million gallons of water per day to the Taiwan-based company’s in-the-works LCD screen plant and nearby industrial and commercial operations in the next-door village of Mount Pleasant.

Racine’s diversion application to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources states “the Foxconn facility would require an average-day demand of 5.8 mgd [million gallons per day].” The other 1.2 million gallons, it notes, would be used for adjacent operations related to the factory.

People who see the Compact as a public-spirited instrument for preserving a precious resource may object to this use of water, but does it violate the terms of the agreement?

What is “largely” public?

The text of the Great Lakes Compact is not particularly detailed. A public utility can send Great Lakes water to a community straddling the basin line as long as “the Water so transferred shall be used solely for Public Water Supply Purposes within the Straddling Community.” Additionally, the Compact defines “Public Water Supply Purposes” as “water distributed to the public through a physically connected system of treatment, storage and distribution facilities serving a group of largely residential customers that may also serve industrial, commercial, and other institutional operators. Water Withdrawn directly from the Basin and not through such a system shall not be considered to be used for Public Water Supply Purposes.”

What does that language mean in practice?

It’s lawful for Mount Pleasant, straddling the basin line, to use Great Lakes water if it’s going “largely” toward residential customers, with some industrial use allowed. However, nowhere in its language does the Compact spell out what “largely” means. It doesn’t seem tied to, say, a specific percentage of the water that must go to residential customers. It’s also not clear which measure of the water used needs to be largely residential, whether it’s referencing a utility’s entire service area both in and out of the Basin, or only the areas served outside of it.

Racine is claiming in its diversion application that because the vast majority of the water it draws from Lake Michigan goes to residential customers, it would still be used for “largely residential” purposes even after tacking on Foxconn’s hefty demands. But the city is making that argument in terms of its entire water service area and total volume sourced. It’s referencing the utility’s overall usage, not simply the 7 million additional gallons it wants to send to Mount Pleasant, nor in terms of the total amount it would be sending to the village, which it already supplies with drinking water.

Foxconn’s Lake Michigan water would flow from the city of Racine. Credit: Wisconsin Public Television

All existing water usage Racine’s water utility accounts for in its Foxconn diversion application is taking place within the Great Lakes Basin. Additionally, its service area as a whole is indeed largely residential by any reasonable definition. But the customers Racine intends to serve outside the Basin via the diversion would be entirely industrial, at least for the time being. Racine makes no argument that even a drop of the water it wants to send to the area of Mount Pleasant that sits west of the basin line would be used for residential purposes.

The language of the Compact dealing with diversions specifically refers to “all the Water so transferred”—that is, pumped to someplace outside the Great Lakes Basin—when defining its “Public Water Supply Purposes” requirement. That reference may be interpreted to mean that specifically the volume of water going outside the Basin needs to be used for “largely residential” purposes. In other words, merely the fact that a water utility’s customer base as a whole is largely residential might not actually satisfy this provision of the Compact.

Again, there’s no specific definition provided for “largely,” but the 7 million gallons Racine is seeking won’t be used for residential purposes at all—the diversion application clearly specifies 5.8 million gallons would go to the Foxconn factory itself, and 1.2 million to other commercial and industrial users nearby.

While the Great Lakes Compact’s language about diversions refers specifically to areas outside the Basin, its definition of “Public Water Supply Purposes” has a more general tone. That language refers to “water distributed to the public through a physically connected system of treatment, storage, and distribution facilities,” which evokes municipal utilities and the areas they serve.

There’s a noticeable tension in the Compact’s language as to whether an entity diverting water should be assessed on what it does throughout its whole service area or just within the diversion area. That possibly opens a loophole to wholly industrial water uses outside the Basin as long as the water passes through one of those “physically connected systems” and said system also has residential customers. Racine’s water utility fits the definition of a public water supply, even as Foxconn is a private, for-profit company.

The language of the Compact does not place cutoffs on what a “largely” public water supply is or how much of any diverted water must be used for residential purposes, said Pete Johnson, deputy director of the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers, which promotes regional cooperation on water-resources issues.

When asked about ambiguities in the Compact, Johnson said its language will have to speak for itself for now. Going forward, he explained, the eight governors in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council would have the power to flesh out what that language actually means.

Making sense of a young law

Adam Freihoefer, head of the Wisconsin DNR’s water use section, oversees the permitting process for the Foxconn diversion. He acknowledges that the Compact’s definition of “Public Water Supply Purposes” has been a major bone of contention as the agency sought public comment.

“That is probably the largest concern when I’m looking in public comments so far,” Freihoefer said. “It’s something legally we need to look at … I don’t really have any answer on where we sit with that.”

Freihoefer could not say what if any precedent or guidance the DNR would be able to draw on in figuring out how the concept of “Public Water Supply Purposes” applies in the case of Racine and Foxconn.

All of these uncertainties underscores the fact that the Great Lakes Compact, for all its regional and global significance, is still a quite young law, ratified by its member states in the 2000s and signed by President George W. Bush in 2008. The city of Waukesha’s bid for Lake Michigan water was its first major test, and beyond that, the compact council hasn’t had a chance to do much debating over what specific aspects of the agreement mean or how they should be applied. In comparison, many state and federal laws have had decades to get chewed over and fleshed out among regulatory agencies and in courtrooms.

Interpretation of the Great Lakes Compact’s terms has been tested by two diversion requests in Wisconsin. Credit: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

The Compact provides mechanisms for member states and other stakeholders to work out grievances about water use, first through an administrative process and then in civil court. But a decade is barely enough time to start nibbling on the sweeping legal questions the Compact’s language raises. Most of the detailed work that goes on to apply the Compact’s requirements is delegated to state governments, which also can’t necessarily resolve issues on behalf of the entire region.

“I think you can write the Compact, but then implementing it is a different beast,” Freihoefer said.

Freihoefer could not comment on how the DNR might decide Racine’s diversion application.

However, the odds are in favor of the agency issuing the city a permit to serve Foxconn with Great Lakes water. Gov. Scott Walker and Wisconsin lawmakers—that is, the Legislature’s Republican majority, as well as some Democrats who crossed the aisle—supported not just $3 billion in state-funded subsidies to entice Foxconn, but also provisions that exempt the company from various state environmental-permitting requirements. The project must comply with state and federal environmental regulations, but there’s political impetus to keep it on a fast track, and the DNR, after years of funding cuts and curbs to its regulatory power, is not immune to pressure.

Setting the stage for regional conflict

At least one state has raised the “Public Water Supply Purposes” language as an issue. In a March 21, 2018 letter submitted to the Wisconsin DNR, New York Department of Environmental Conservation official Diane English noted how the Great Lakes Compact defines public water supplies, writing “it is unclear that the proposed diversion is largely for residential customers where the water is intended to facilitate the construction and operation of the future industrial site of the Foxconn facility.”

A department spokesperson explained that New York is merely raising questions at this stage, not raising objections to the diversion. Moreover, the state, which is a member of the Compact, has not decided whether it would take further action if and when the Wisconsin DNR approves the diversion.

The designated representative to the Great Lakes compact council from Michigan, attorney and environmental engineer Grant Trigger, emailed the DNR on March 21 to ask what Racine’s basis was for concluding that the requested diversion is a public water supply use. He also asked about the amount of water the Foxconn factory would use and not be able to return to the Great Lakes, known as consumptive use.

The state of Michigan, which courted Foxconn with proposed subsidies, is also still staking out its position about the company’s bid for water inside Wisconsin.

Trigger said he’s not yet sure what precedent Wisconsin or other states should draw on when applying the Compact’s language about public water supplies to this specific situation.

“Where we are right now is we’re still trying to understand the context of this request, because the Compact is very specific in some places and very general in other places,” he said.

Illinois has also weighed in on Racine’s diversion application, but for different reasons. A March 21 letter from the office of the Illinois Attorney General to the DNR objected to what it described as a lack of detail provided by Foxconn and Racine about how wastewater from the factory would be treated.

Regulation of Great Lakes water use is regulated by the overlapping terms of the Great Lakes Compact alongside state and provincial laws. Credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Not everyone raising the “largely” public water supply issue is an anti-diversion hawk.

John Skalbeck, a geosciences professor at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside in Kenosha, was a vocal proponent of Waukesha’s request for Great Lakes water; a promotional website the city set up to marshal public support for its project even touts his arguments in favor of the diversion. But Skalbeck vehemently opposes the Foxconn diversion.

In a March 21 letter to the DNR, Skalbeck wrote that “approving the Racine Application to divert Great Lakes water for a single industrial user would set a terrible precedent for future water diversion considerations under the Great Lakes Compact.”

This difference in support for the two diversion proposals is unusual, as most people in Wisconsin political and environmental circles tend to either align in support or opposition to both. Skalbeck takes a more nuanced approach, though, seeing Waukesha’s diversion as legally and scientifically justified, and Foxconn’s as a clear violation of the Compact’s terms.

Skalbeck noted that the compact council blocked Waukesha’s attempt to expand its water service area through access to Great Lakes water. During its application process, Waukesha reduced the amount of Lake Michigan water it requested, and agreed to use those supplies only for the geographic areas its water utility served at that time, and not any future areas where it might expand service.

On the other hand, Racine’s plans for Foxconn involve sending Great Lakes water to an area of Mount Pleasant that its utility currently does not already serve. Skalbeck argues in his letter opposing the Foxconn diversion that the Waukesha case “signals agreement that diverted Great Lakes water can NOT be used for an expanded service area.”

Freihoefer would not say whether DNR is preparing for the possibility of future administrative reviews or litigation prompted by complaints from other states.

For his part, Skalbeck can see the Foxconn diversion potentially ballooning into a fight that goes beyond Wisconsin’s borders.

“I suspect that the permit will be issued by DNR,” he said, “and when it does, I think a number of parties will probably bring legal action challenging that decision on the basis of the public supply definition.”

Scott Gordon is a reporter for WisContext. He’s based in Madison, Wisconsin.

WisContext produced this article as a service of Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

Support great science journalism. Donate to Science Friday.

Spread the word