A federal appeals court in April 2018 ruled that Florida does not have to fix its process for restoring voting rights to people convicted of felonies. The order overturned a lower court's ruling that the process was unconstitutional because it includes no standards or guidelines and leaves the decision entirely in the hands of Gov. Rick Scott (R) and the rest of the state's clemency board.

After his predecessor streamlined the process to re-enfranchise hundreds of thousands of voters, Scott implemented a mandatory five-year waiting period for people who have completed felony sentences. Since he took office in 2011, only 3,000 people — out of 1.5 million eligible voters — have had their voting rights restored. Many applicants have waited years and not yet received a decision.

Despite the court's ruling, Florida voters have a chance to reject the status quo by approving a constitutional amendment that will be on the ballot in November. The amendment would automatically restore voting rights to anyone convicted of a felony (other than murder or sex crimes) after they complete their sentences, including probation or parole.

Scott had called a meeting of the clemency board this week, after the lower court had ordered that a new system be in place by April 26. But he cancelled the meeting after the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned that order.

The 11th Circuit cited rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court as well as the 14th Amendment, which allows the revocation of voting rights for "participation in rebellion, or other crime." The court noted that "the Governor has broad discretion to grant and deny clemency, even when the applicable regime lacks any standards."

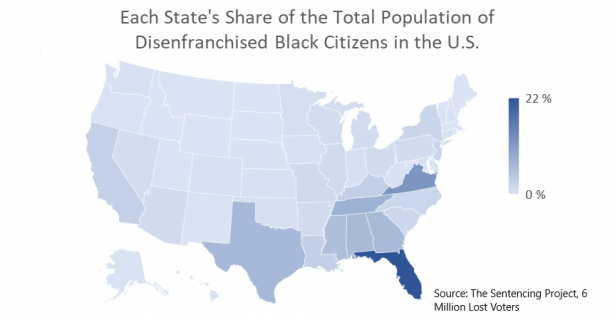

A re-enfranchisement system that discriminates against certain people would be unconstitutional, the court said, but the voters in this case did not make that claim. In Florida, 21 percent of African-American voters have been disenfranchised by this system. The state is home to nearly a quarter of all the disenfranchised African Americans in the U.S.

Disenfranchisement's disparities

Other Southern states — Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia — have similarly high rates of disenfranchisement for African Americans, according to a report from the Sentencing Project. In those states and in Alabama and Mississippi, more than 7 percent of the total voting-age population is disenfranchised because of criminal convictions. These states bar people with felony convictions from voting even after they've completed their sentences. The remaining seven states in the South allow felons to vote after completing any required probation or parole. Twenty states outside the South have more lenient rules.

Critics of the South's disenfranchisement laws often point to their origin in the Jim Crow era and their disproportionate impact on African Americans. Two lawsuits have been filed against Mississippi's disenfranchisement rule, which requires those who have completed their sentence to get a pardon from the governor or a law passed by the legislature — something only a handful of voters have done in recent years. The voters in one of the lawsuits argue that the felonies originally listed in the 1890 Mississippi Constitution — bribery, theft, arson, perjury, and other property crimes — were chosen because the drafters believed that black citizens were more likely to be convicted of those offenses.

In 1896, six years after Mississippi's disenfranchisement provision was drafted, the state Supreme Court ruled that the limitations on voting were intended "to obstruct the exercise of suffrage by the negro race." The court said that the framers of the state constitution had done everything they could "under the limitations imposed by the federal Constitution" to achieve that goal. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned this decision and reinstated the disenfranchisement rule.

In Alabama, the current state constitution adopted in 1901 (whose framers explicitly said they intended to "establish white supremacy") did not allow people to vote if they had been convicted of crimes that met the vague standard of "moral turpitude." The U.S. Supreme Court struck down this provision in 1985 — but the state responded by passing a law that used the exact same standard. After voting rights advocates filed a lawsuit challenging the system in 2016, the state passed a law that clearly defined "moral turpitude" and thus allowed tens of thousands of people to get their voting rights back.

In Virginia, Gov. Ralph Northam (D) is continuing his Democratic predecessor's practice of reinstating voting rights to everyone who has completed a felony sentence. The previous governor of Kentucky, a Democrat, tried something similar, but current Gov. Matt Bevin (R) promptly overturned the decision.

These disenfranchisement rules have made an astounding number of black men ineligible to vote. In many Southern states, black men gained the right to vote in 1868, after they participated in post-Civil War conventions that rewrote state constitutions. But now, 150 years later, around 30 percent of black men in Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi are not eligible to vote because of felony disenfranchisement laws.

Criminalizing confusion

Meanwhile, these felony disenfranchisement laws create a new class of criminals: people who vote while ineligible.

Given that President Trump and other conservatives are trumpeting unjustified claims of voter fraud, voting rights advocates are concerned that ineligible voters will be scapegoated. A woman in Texas who had been convicted of felony tax violations was recently sentenced to five years for voting while on supervised release, but she recently filed an appeal requesting a new trial. The woman's attorney argues that she was actually eligible to vote and that Texas law is unclear.

A few states are working to ensure that people convicted of felonies plainly understand when their voting rights are restored in order to avoid criminal charges for ineligible voting. For example, the Louisiana legislature passed a bill last year to require criminal justice authorities to more promptly inform elections officials of felony convictions.

And in North Carolina, the state Board of Elections has worked with the courts and probation officers to ensure that people know when they are prohibited from voting. Since the 2016 election, the board has drafted public education documents on the loss of voting rights. It also drew up a notice that is given to people convicted of a felony stating, "Upon completion of your sentence (including probation and parole) … your citizenship rights are automatically restored."

Billy Corriher joined the Institute for Southern Studies in January 2018 as senior researcher, where his work includes a focus on judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina. Billy has written about these issues for ThinkProgress, The Hill, USA Today, The Los Angeles Times, Newsweek, and the News and Observer. He has been interviewed by NPR’s "Fresh Air" and other media outlets. Before attending law school, he was a reporter for the Clayton News-Daily in Georgia. Billy received his bachelor's degree in political science with a minor in journalism from the UNC-Chapel Hill, as well as a law degree and master's in business administration from Georgia State University.

Spread the word