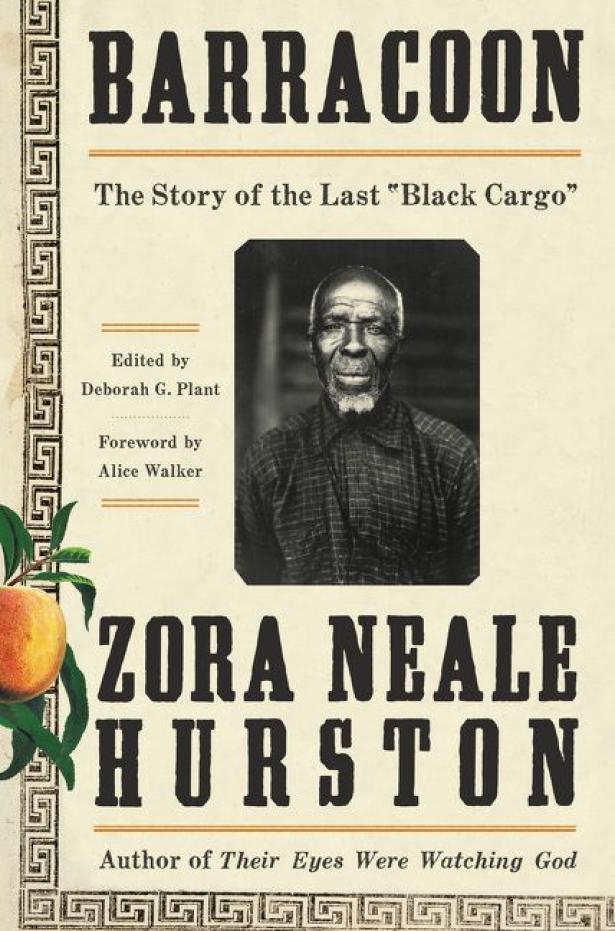

Barracoon

The Story of the Last "Black Cargo"

Zora Neale Hurston

Amistad

ISBN: 9780062748201

Like gifts from the grave, the words of Zora Neale Hurston, revered mother of black literary and womanist canon, have come back to bless us.

In 1931, Viking Press rejected Hurston’s manuscript for Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” the not-yet-novelist and folklorist’s first-person account of 89-year-old Oluale Kossula (slave name: Cudjo Lewis), because it was written in black “dialect.”

She refused to make the changes requested by Viking, and Barracoon languished in obscurity for 87 years, until HarperCollins announced that it was releasing it in May 2018.

As the introduction by historian and editor Deborah G. Plant points out—there exist only about eight accounts that chronicle or even mention the Maafa, or Middle Passage, written by black people. None are from black women.

Kossula was uniquely placed in time and space—a remarkable prospect, of which Hurston writes, “Of all the millions transported to Africa, to the Americas, only one man is left.”

Of course, there were hundreds, if not thousands, of the chronicles of whites and their exploits in the sale of humans. Hurston laments:

All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold. The Kings and Captains whose words moved ships. But not one word from the cargo. The thoughts of the “black ivory,” the “coin of Africa,” had no market value. Africa’s ambassadors to the New World have come and worked and died, and left their spoor but no recorded thought.

In short, Hurston knew what a precious black heirloom she had in Kossula and refused to compromise that to the whims of a publisher who saw no worth in black history, lives or folklore.

Hurston first met Kossula in 1927, when her mentors, anthropologist Franz Boas and Black History Month founder Carter G. Woodson, jointly financed her trip to Alabama to get Kossula’s account of the raid on his village when he was 19 years old. Kossula was brought to the U.S. illegally via the slave ship Clotilda more than 50 years after Congress outlawed the importation of enslaved Africans into the United States.

Four years later, Hurston returned to Plateau, Ala., aka “Affiky Town” (Africatown), a community co-founded by Kossula and other survivors of the Clotilda, and one of few places in America (Hilton Head and the Sea Islands of the Carolinas are others) that tendered an unbroken bond to Africa’s culture, language and customs in America.

Hurston spent more than three months interviewing Kossula, where they shared peaches and crabs, watermelons and tears and parables. Kossula has an “incredible memory,” writes Hurston, who uses both “Kossula” and “Cudjo” interchangeably in referring to him, but alas, she explains, a life rife with a series of incredible pain and loss.

Without ruining the mystery, the things that I found most intriguing from Kossula’s story were that in his account of the raid on his village, the first Dahomey warriors that came in were women; the unique way in which Kossula’s village punished the crime of murder; and the way in which the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Kossula’s son was shot and killed by a black policeman, and Kossula himself was injured by a train and robbed by a white lawyer for his efforts. There was also some tension between Africans born on the continent and black Americans born here (Kossula’s six children, given both an American and African name, were bullied by African Americans as “savages,” but a free black man, “Free George, “de best friend the Africans got”).

Hurston also had to disabuse herself of the notion that whites were the only ones complicit in the transatlantic slave trade after hearing Kossula’s story. She writes:

But the inescapable fact that stuck in my craw, was: my people had sold me and the white people had bought me. That did away with the folklore I had been brought up on—that white people had gone to Africa, waved a red handkerchief at the Africans and lured them aboard shop and sailed away.

This elder taught Hurston much, and she was the perfect receptacle for his commonly dreadful, deeply painful, but singularly amazing story, including this amusing exchange Hurston recounts when Kossula starts his life story with his grandfather:

“My grandpa, he a great man. I tellee you how he go.”

I was afraid that Cudjo might go off on a tangent so I cut in with, “But Kossula, I want to hear about you and how you lived in Africa.”

He gave me a look of scornful pity and asked, “Where is de house where de mouse is de leader? In de Affica soil, I cain tellee you ‘bout de son before I tellee you about de father; and derefore you unnerstand me, I cain talk about de man who is father till I tellee you bout de man who he father to him now, dass right ain’t it?”

Barracoon is an incredible work of historical nonfiction that honors the dignity, calamity and resilience of a people brought here, chronicled by “a genius of the South.”

We are thankful that the story of one man—out of millions—made it, and that the woman who procured it also respected and protected it enough to see it through.

Angela Helm is Contributing Editor at The Root.

Spread the word