Albert Einstein is back in the news, but not because someone has disproved or confirmed one of his theories. The publication of Einstein’s travel diaries last week reveal that he wrote some racist things about the Chinese back in the early 1920s. The media have jumped on Einstein’s observations to undermine his reputation as a progressive, suggesting that the world-renowned physicist was a hypocrite. “Einstein's travel diaries reveal physicist's racism,” BBC News headlined its story. USA Today’s version was: “Einstein was a racist? His 1920s travel diaries contain shocking slurs against Chinese people.” Wrote Fox News: “Einstein's diaries contain shocking details of his racism.”

Princeton University Press (in coordination with the Einstein Papers Project at the California Institute of Technology) just published The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein: The Far East, Palestine, and Spain, 1922–1923, translated into English for the first time. In his journal, written while he was in his early 40s and still living in Europe, Einstein jotted down his observations during his wanderings through China, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, Spain, and Palestine about science, art, politics, and philosophy.

The media has focused on several racist comments, including Einstein calling the Chinese an “industrious, filthy, obtuse people” and "often more like automatons than people.” He wrote that China is a “peculiar herd-like nation" and that “It would be a pity if these Chinese supplant all other races. For the likes of us the mere thought is unspeakably dreary.” In contrast, he wrote that the Japanese were "pure souls" who are "unostentatious, decent, altogether very appealing."

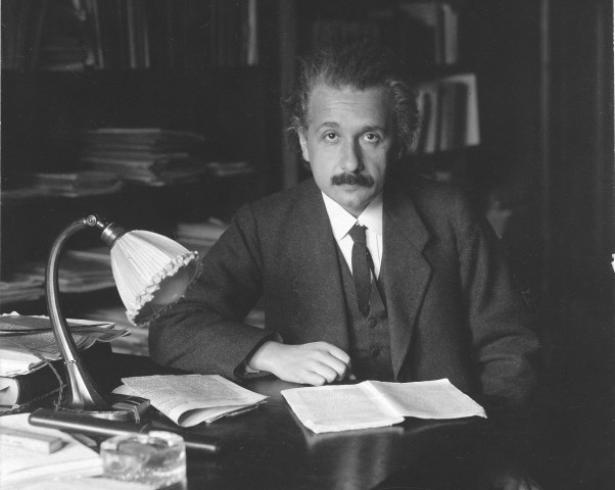

Einstein was already world-famous for his theory of relativity. He won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1922. Indeed, Einstein was the world’s first celebrity scientist. He appeared on the cover of TIME magazine four times (1929, 1946, 1979, and 1999, when TIME selected Einstein as its Person of the Century). Today, dozens of different posters of Einstein, often adorned with one of his famous quotes, hang on walls in dorm rooms, school classrooms and offices around the world. People who know almost nothing about Einstein’s scientific accomplishments (except, perhaps, that he created something called the theory of relativity, or that he is connected with the formula E=mc2) associate his name and image (including the unruly hair and the baggy sweater) with “genius.”

I included Einstein in my book, The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame, published in 2012. I pointed out that Einstein was a pacifist, a humanist, a socialist and a Zionist as well as a scientist. In a speech in New York in September 1930, he challenged fellow pacifists to replace words with deeds. If only 2 percent of those called up for military service refused to fight, he said, governments would be powerless, because they could not send so many people to prison.

Forced to flee Germany because he was Jewish, a socialist and an outspoken opponent of the Nazis, he moved to the United States in 1933, first joining the faculty at Cal Tech and then the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton. Once in the U.S., he became deeply involved in the civil rights movement.

At different times in his life, he was harassed by both the German and the U.S. governments for his political views. During the Cold War, the FBI’s file on Einstein grew to over 1,800 pages, listing dozens of allegedly “subversive” organizations that he supported. As his biographer Jim Green noted, “his mail was monitored, his phone tapped, his home and office searched and his trash examined.” Right-wing Senator Joseph McCarthy called Einstein an “enemy of America.”

So—would I re-evaluate my inclusion of Einstein in my book, knowing what I know now in light of these journal entries?

I would certainly incorporate Einstein racist comments in my profile of him, but that wouldn’t exclude him from being in the pantheon of great American radicals and progressives. As I point out in my book, none of the 100 people in my Social Justice Hall of Fame was (or is) a saint. They all had vision, courage, persistence, and talent, but they also made mistakes. Some had troubled personal lives. Some expressed views that many progressives considered objectionable at the time, and are certainly objectionable today.

Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood and a crusader for women’s health and birth control, briefly endorsed eugenics. Theodore Roosevelt’s was a foe of big business, but his “big stick” imperialism outraged many progressives. Alice Paul, the great women’s suffrage leader, was an anti-Semite.

Eleanor Roosevelt also absorbed the casual anti-Semitism of her upper-class WASP upbringing. In 1918, shedescribed Harvard Law professor Felix Frankfurter, then serving as an advisor to President Woodrow Wilson, as “an interesting little man but very Jew.” That same year, after attending a party for Bernard Baruch when her husband Franklin was Assistant Secretary of the Navy, she wrote to her mother-in-law, ''I'd rather be hung than seen at'' the party, since it would be ''mostly Jews.'' She also reported that ''The Jew party was appalling.” Not much later in her life, however, she became a crusader for Jewish causes, a foe of anti-semitism and racism, and a powerful (though unsuccessful) advocate for getting her husband to do more to save Jews from the Nazi holocaust.

Earl Warren is best known as the liberal chief justice of the Supreme Court during the 1950s and 1960s, including the historic Brown v. Board of Education case against school segregation. But when he served as California’s attorney general during World War II, he was a moving force behind the compulsory removal of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast to inland internment camps without any charges or due process. Likewise, Theodor Geisel’s racist depictions of Japanese Americans in his editorial cartoons (under his pen name Dr. Seuss) for the radical newspaper PM during World War II contradicted his lifelong support for tolerance and his opposition to bullies and tyrants.

Jackie Robinson’s attack on left-wing activist and singer Paul Robeson, during the pioneering baseball player’s testimony before Congress in 1949, reflected Cold War tensions; Robinson, who was a civil rights activist during and after his playing career, later said he regretted his remarks. The iconic feminist leader Betty Friedan, founder of the National Organization for Women and author of path breaking book The Feminist Mystique (1963), was homophobic. Friedan worried that the involvement of “mannish” or “man-hating” lesbians within the movement would hinder the feminist cause. Senator Paul Wellstone voted in favor of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, which outlawed federal recognition of same-sex marriage. He later said he regretted his stance on the issue.

Some of these views may be understandable in their historical context. It is important to recognize that although that while radicals and progressives are often pioneers in most aspects of their thinking, they cannot entirely transcend the political realities and social prejudices of their times. What’s important is whether their views evolve, whether they regret their former attitudes, and whether they change their behavior.

At the time that Einstein wrote his racist comments about the Chinese in his diaries, these stereotypes were widespread. They provided justification for the Chinese Exclusion Act, which Congress passed in 1882 to ban all Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S., and which was still the law when Einstein was visiting China in the 1920s.

Once he arrived in the U.S., Einstein often spoke out frequently for the civil rights of African Americans. He joined a committee to defend the Scottsboro Boys, nine Alabama youths who were falsely accused of rape in 1931 and whose trial became a cause of protest by leftists around the world. He lent his support to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and he corresponded with scholar-activist W. E. B. Du Bois.

In 1937, the great African American opera singer Marian Anderson gave a concert at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, but she was denied a room at the whites-only Nassau Inn, Princeton’s leading hotel. Einstein invited Anderson to stay at his house. Whenever she visited Princeton thereafter, she stayed at his home.

In 1946, Einstein accepted an invitation from the singer and activist Paul Robeson to co-chair the American Crusade to End Lynching, which the FBI considered a subversive organization because its members included radicals trying to pressure President Harry Truman to support a federal law against lynching. That year, almost a decade before the Montgomery bus boycott sparked the modern civil rights movement, Einstein penned an essay, “The Negro Question,” in the January 1946 issue of Pageant magazine, in which he called American racism the nation’s “worst disease.” While effusively praising America’s democratic and egalitarian spirit, Einstein noted that Americans’ “sense of equality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skins.” Having lived in the United States for little more than a decade, Einstein wrote, “The more I feel an American, the more this situation pains me.”

In 1946, Einstein visited Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the first school in America to grant college degrees to blacks and the alma mater of poet Langston Hughes and attorney Thurgood Marshall. He gave a physics lecture to Lincoln students and also gave a speech in which he repeated his observation that racism is “a disease of white people.” He added, “I do not intend to be quiet about it.” The media typically covered Einstein’s talks and political activities, but only the black press reported on his visit to Lincoln. At the time, few prominent white academics bothered to speak at African American colleges and universities; Einstein was making a political statement with his visit to Lincoln, but it was consistent with his other political views and activities, including his strong opposition to racism.

In 1948, Einstein supported Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party campaign for president. He was part of a coalition of radicals and progressives who admired the former Vice President’s opposition to the cold war, his pro-union views and his firm support for civil rights.

Einstein coupled his radical views on politics and race relations with equally radical analyses of economics. In a 1931 article, “The World as I See It,” he wrote, “I regard class distinctions as unjustified, and, in the last resort, based on force.” In a 1949 essay, “Why Socialism?” published in the first issue of the journal Monthly Review, he noted that “the crippling of individuals” is “the worst evil of capitalism.” He criticized capitalism’s “economic anarchy” and the “oligarchy of private capital, the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by democratically organized political society.” He believed that a socialist economy had to be linked to a political democracy; otherwise, the rights of individuals would be threatened by an “all-powerful and overweening bureaucracy.” It was this radical humanism that led him to oppose Soviet communism.

Einstein was horrified by the human carnage that accompanied the U.S. bombing of Japan in 1945, and he worried about the escalation of the arms race and nuclear weapons during the cold war. He told his friend Linus Pauling, a fellow scientist and peace activist, “I made one great mistake in my life—when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification—the danger that the Germans would make them.”

In 1946, Einstein became chair of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, formed to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, including the hydrogen bomb. Interviewed on Eleanor Roosevelt’s television program in 1950, Einstein said, “The idea of achieving security through national armament is, at the present state of military technique, a disastrous illusion.” In 1955, shortly before his death, Einstein and philosopher Bertrand Russell persuaded nine other prominent scientists to sign the Russell-Einstein Manifesto calling for the abolition of atomic weapons and of war itself.

A victim of anti-Semitism as a young scientist in Germany, Einstein became a vocal advocate for a Jewish state that he hoped would liberate Jews from persecution and encourage the flowering of Jewish culture. He hoped that Jews and Arabs would be able to share power and coexist in one county and was disappointed when that did not happen. Once Israel was created in 1948, he became a strong supporter of the nation, especially the socialist principles embodied in its founding. In 1952, Israel’s Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion offered Einstein the presidency of Israel, a ceremonial position. Einstein was flattered, but declined.

A year before his death, Einstein explained that he wrote and spoke out on public issues “whenever they appeared to me so bad and unfortunate that silence would have made me feel guilty of complicity.”

The racist observations in Einstein’s diaries are appalling but they shouldn’t be surprising. They reveal that Einstein was not immune from some of the prejudices and stereotypes of his time. If we require our progressive heroes to be saints, we won’t have many people to admire.

Peter Dreier teaches politics and chairs the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His latest book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books, 2012).

Spread the word