Sometimes history moves fast.

Almost two years ago, when I wrote “Blueprint for a New Party,” I thought of it mainly as a way to stimulate debate, not as an immediately actionable program. In the article, I called for the creation of a national left-wing political organization that, unlike the Democrats, would act in most respects like a genuine party: with a mass membership democratically determining the party’s program and forcing its office-holders to adhere to it.

It would differ from a conventional party in only one respect: it wouldn’t seek a separate ballot line. Instead, it would run its candidates on whichever line made the most sense for the race in question: an independent line in some cases, but more often — at least at first — in Democratic primaries.

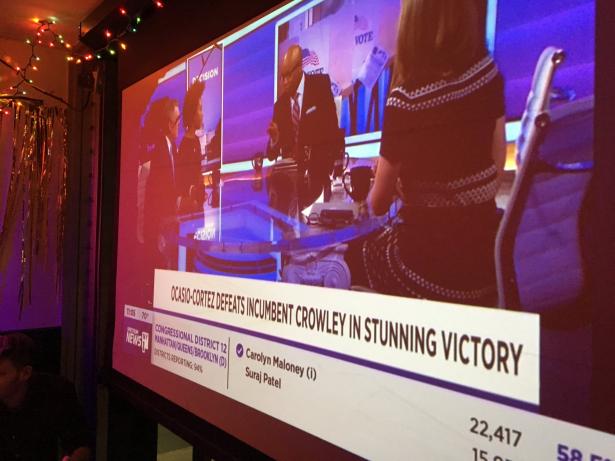

Since then, there’s been an explosion of left-wing activism, including a more than quintupling of DSA’s membership, and the idea of independent, organized left-wing electoral politics has taken on a life of its own. On the heels of a series of victories for DSA-backed state and local candidates, the defeat of Queens Democratic Party boss Joe Crowley at the hands of DSA member Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez represents a kind of proof-of-concept that independent socialist electoral politics can work.

But from the standpoint of my proposal in “Blueprint,” the most interesting aspect of Ocasio-Cortzez’s campaign wasn’t her victory, but her attitude toward the Democratic Party. In a televised pre-election debate with Crowley, the Queens Democrat posed a question to her that he no doubt thought was a clever trap. Here’s what he said:

This is, I think, a very exciting time for our party. … We have a chance to win back the House of Representatives. People know what’s at stake. They know that this president is an existential threat, that our lives are at stake. And so, what I believe is that we have to unite in our party, to make sure that we are united when we go into this election in November.

I’m willing to make a pledge tonight, that if you win this primary and have the support of the people of the 14th congressional district then I will fully endorse and … and vociferously and robustly work for your election to Congress. My question to you is, will you do the same for me if the people of the 14th Congressional district choose me as their nominee?

In the playbook of US politics, this has historically been the go-to “gotcha” question to level at any insurgent primary candidate who criticizes the party’s political outlook: fine, criticize all you like, but will you support me on election day? The question is a trap. If the insurgent says “yes,” he or she has essentially told their own supporters: “Whatever I say now, when it comes down to it, I’m a loyal Democrat; whatever I might promise today, whatever political alternative I claim to embody, I’ll end up doing the opposite if Chuck Schumer or Nancy Pelosi needs me to.”

But God help them if they say “no.” Then they’ll be a spoiler. A Republican enabler. Or in nineteenth-century lingo, a “sorehead.”

But instead of falling into the trap, AOC, deftly sidestepped it. Here was her reply:

Well, Representative Crowley, I represent not just my campaign, but a movement. I am proud to be endorsed by organizations like Democratic Socialists of America, the Movement for Black Lives, Muslims for Progress, and so on. And as a result, we govern ourselves democratically. So, I would be happy to take that question to our movement for a vote and respond in the affirmative, or however they respond.

What Ocasio-Cortez’s answer reveals, I think, is that rooting left-wing electoral politics in independent membership organizations isn’t just a way to acquire electoral muscle on the ground. It’s also a powerful tool for candidates and office-holders to use in political combat. When you ground your decision-making in the will of a democratically organized constituency, on the one hand, yes, you’re relinquishing some power: you now have an organized constituency to answer to, and sometimes they won’t go along with what you want.

But on the other hand, that arms you with a powerful form of legitimacy whenever you find yourself butting heads with powerful, entrenched party interests: Sorry, Chuck and Nancy, I don’t represent you, I represent those who worked to put me in office.

And now Ocasio-Cortez has gone further. In an interview with Dan Denvir on Jacobin’s The Dig podcast, she was asked about the prospects for organized left politics within Congress itself:

DD: Looking ahead to you entering Congress (I’m feeling fairly confident about November but don’t want to jinx you), the Right has successfully used groups like the House Freedom Caucus to push their agenda. Do you think that the Progressive Caucus, which has been much lower profile for a long time but is significant, can do the same for the Left?

AOC: There’s potential. It all depends on how unified that caucus is. The thing that gives the Freedom Caucus power is not their size but their cohesion. Right now the Progressive Caucus is bigger than the Freedom Caucus, actually. But sometimes they vote together, sometimes they don’t.

The thing that gives a caucus power is that they can operate as a bloc vote to get things done. Even if you can carve out a sub-caucus of the Progressive Caucus, a smaller bloc but one that operates as a bloc, then you can generate real power.

I think with that, it’s just really about, “We’ll see.” As unapologetic and strong as I am in my messaging and my belief, my personal style is as a consensus builder. I like to think that I’m persuasive. I’m usually able to make the pragmatic case for doing really ambitious things. Not to say that I can carry a caucus on my back or anything, but I think that there’s a willingness right now. We’ll see if that willingness is still there in January. I think that if you can even carve out a caucus of ten, thirty people, it does not take a lot if you operate as a bloc vote to really make strong demands on things.

What we’re witnessing in embryo is the emergence of a new way of approaching left-wing politics. It’s still early, and the obstacles to the sort of plan AOC describes are formidable. She won’t find many other Alexandria Ocasio-Cortezes in the House Progressive Caucus, and the pressure she’ll come under to act like a “team player” and go along with the leadership will be intense.

But two things in particular are immensely encouraging. First, she obviously understands the obstacles she’s facing, as her quote makes clear. She’s no naïf. And second, the mere act of floating this idea gives her power. From now on, every time the House Democratic leadership finds itself in conflict with its left flank, this idea will pop up; it will be discussed; and it will serve as an implicit source of bargaining leverage.

These ideas can’t be put back in the bottle. And as someone once pointed out, ideas becomes a material force once they’ve gripped the masses.

===

Spread the word